Oliver Stone: Any NSA attacks on ‘Snowden’ would have been stupid

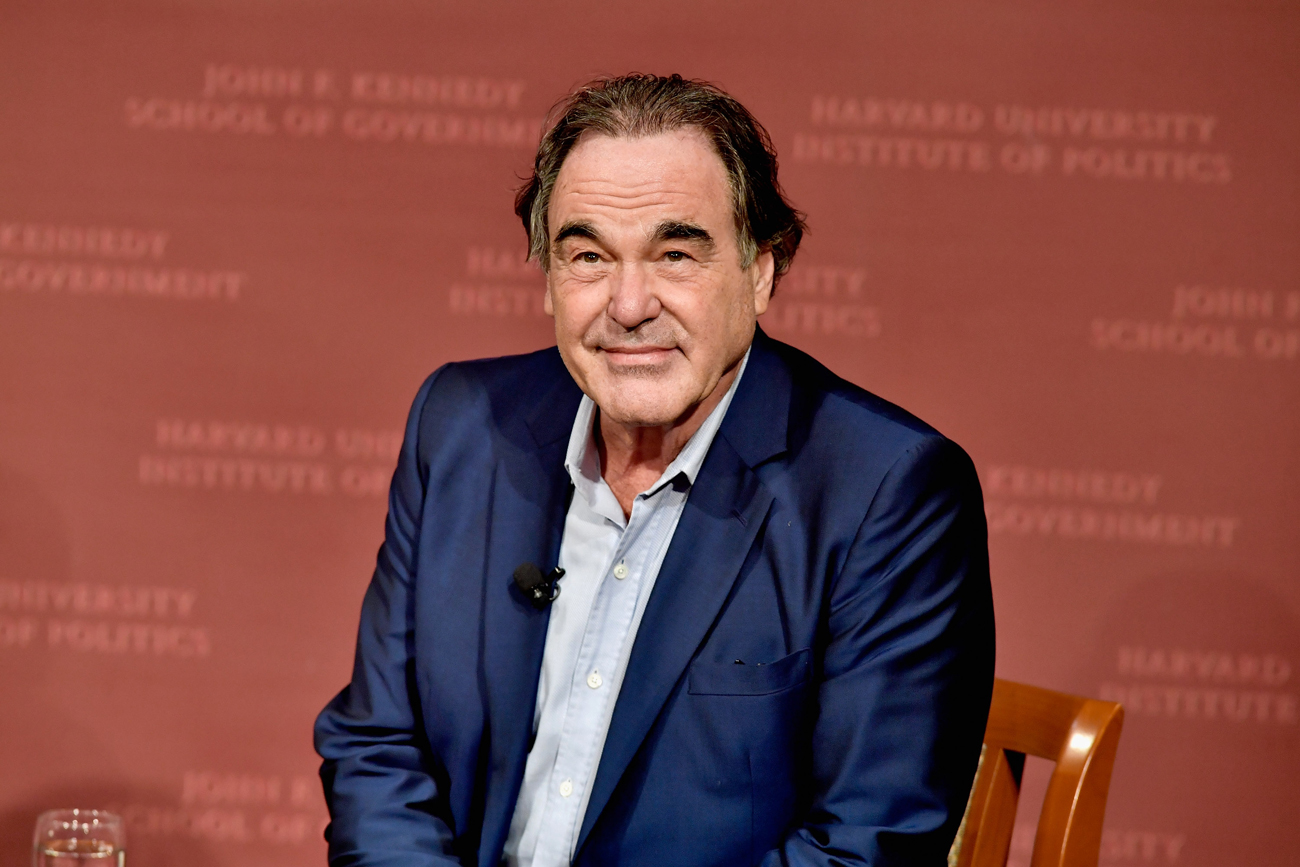

Director Oliver Stone discusses his new film 'Snowden' with moderator Ron Suskind at Harvard University's John F. Kennedy School of Government Institute of Politics on Sept. 12, 2016 in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Getty ImagesOn Sept.15, the movie “Snowden,” directed by the iconic filmmaker Oliver Stone, will hit the screens in Russia, a day before it opens in the United States. As the title implies, the film tells the story of one of the most controversial characters in recent American history – Edward Snowden, the former CIA contractor who in 2013 released documents revealing the extent of the U.S. government’s surveillance of suspected terrorists, world leaders and American citizens under the pretext of fighting terrorism.

Even for a filmmaker of Stone’s scale, taking on such a recent and controversial topic was difficult – the film was in the works for two years. But the subject matter was right up Stone’s alley, with its combination of political intrigue, government plots and, in the center of it all, a disillusioned American patriot.

Stone spoke with Igor Dunaevsky, Rossiyskaya Gazeta’s Washington, DC correspondent, about the making of the film and his ongoing suspicions. As Stone warned Dunaevsky at the beginning of the conversation, which took place via telephone: “I’m sure we’re being tapped or whatever. The interview could be overheard as well. So I think we should be careful as much as possible. You tell me what you need, and I’ll do my best.”

RG: Oliver, given your advice, let me ask this. Weren’t you and your team afraid of putting yourself in the NSA’s spotlight because of the movie? Snowden’s revelations had a severe impact on the U.S. intelligence community, particularly on the NSA. Why did you shoot in Germany?

Oliver Stone: We felt it was safer to make it in Germany. Germany was more anti-surveillance because of it’s own past. Going back to 2014, remember it all — it all was fresh news and was scary. In the U.S., people were saying hysterical things against him [Snowden]. Like that he was working for Russia or for China, that he was a traitor, a spy. It was quite heated. In that environment, we found that if we would shoot in the U.S., we would not have the same friendly feeling. We felt that too many people were against him. The polling showed that Germany was far more favorable to his actions as opposed to the U.S., where 60 percent were against him. That changed later by the way, it became much more friendly. But not then.

'Snowden' / Source: Kinopoisk.ru

'Snowden' / Source: Kinopoisk.ru

But actually we shot two weeks in the U.S. We had the character playing Snowden walking right in front of the residence of President Barack Obama. We also went to Hawaii, Hong Kong and Moscow.

RG: Did you feel any pressure from the U.S. government or intelligence agencies while working on the movie? How did you contact Snowden? He is probably carefully watched by the NSA and CIA.

O.S.: Frankly, we took precautions with the script, didn’t talk on it over [the] phone or email. We went offline, we had our conversations encrypted as much as possible. It was quite complicated.

I would never talk on the phone with Snowden. I would go to Moscow. We were working in Munich, and it was closer. Or I would send him a message through his lawyers. One was in Washington — Ben Wizner, the other one was Anatoly Kucherena in Moscow.

I didn’t feel NSA would attack us on the film. That would have been stupid and backfire on them. I’ve done these things many times before. I felt that I was protected because I was public and legal about my business affairs.

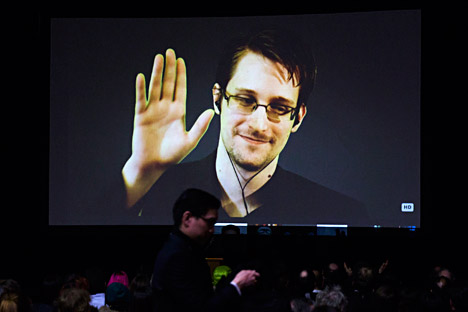

Snowden and 'Snowden'

RG: What kind of advice did Snowden share with you? Did he watch the film? Did he like it?

O.S.: I took it to him twice. Yes, he got it. He was helpful on both sides. He understands the computer world very well and helped with technical corrections. ‘Cause he was there, he knows the language. At the same time, he understands the needs of drama. You can’t have something going on and on… You need shape, a form, to this thing. We can’t film some of the computer stuff he talked about. We had to create it artificially, but it gives you a sense of what a computer can do.

RG: Many questioned his motivation. In the U.S., he was accused of narcissism, seeking fame and popularity. The government calls him a traitor, while for a liberal part of society he is a hero. How did you feel about it? Why did he do it?

O.S.: This was my job as a dramatist. You have to see the movie to understand it. I can’t sum it up in a journalistic statement.

There’s a number of reasons. He was a patriot. He really believes in the Constitution, almost like a Boy Scout. And his oath of loyalty was to the Constitution, not to the CIA or the NSA. We show you his progression in the intelligence community, his different jobs and what he sees in these different jobs. And it’s horrifying to him.

Video by Open Road Films / YouTube

On top of that he had a life. If you take his relationship with his girlfriend, Lindsay Mills, into account, it’s a 10-year relationship. And I think giving her up was one of the big aspects of that story and was most difficult for him.

You have to take into account his epilepsy, that feeling for the first time in his life that he’s mortal, that there’s a limit to this life. And when young man runs into that, he has second thoughts about what is he doing in this life.

In the movie, you see his development from about 20 to 29. That’s quite a step. You learn as you go, you change, that’s what life is about. This movie is really about how to keep your soul.

How the world changed post-Snowden

RG: Snowden’s action served to open a discussion in the U.S. about the delicate line between democracy, human rights and security, fighting terrorism. After his revelations, the administration took some steps to limit electronic spying. As you’ve mentioned, the U.S. society also was re-thinking the issue. Recently former U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder called Snowden’s actions a “public service.” In what direction is this dialogue moving?

O.S.: Frankly, Mr. Snowden himself said that Mr. Obama made some reforms like “changing the drapes in the room.” Spy agencies can go back and retroactively get what they want. I think all Americans feel that we’re being watched, potentially watched. I grew up in early 1950s in New York, and I remember that Cold War feeling from my father. The same chilling effect and fear exists in all of us, and we watch what we say, because if you express yourself openly, you might become a class enemy or enemy of the state — enemy of business or corporations more likely.

The big reform that happened after Snowden, in my opinion, was the concept of encryption. It was carried through private corporations. Some of them were major collaborators of the government in the period before Snowden. That’s not to say that biggest phone companies, like AT&T or Verizon, have changed their ways. I doubt it. But Google or Facebook have gone ahead. Not because they believed in what Snowden was doing, but because they didn’t want to lose their customer base. I think other commercial outlets would have presented products with encryption and customers would have gone.

RG: Was that a right thing to do for Russia, to give asylum to Mr. Snowden?

O.S.: Frankly, I asked Mr. Putin about that, and he gave me a very good answer, but I can’t tell you that until the film is released. But the fact that Mr. Putin gave asylum to Mr. Snowden has affected his relations with the West. I don’t think the United States, which dominates the West, was very happy with him.

RG: You were working on a documentary about the president of Russia, Vladimir Putin. How is that going?

O.S.: I’m completing it, yes. Maybe it will be done next year.

First published by Rossiyskaya Gazeta

Read more: Oliver Stone on why Russia is a natural ally of the U.S.>>>

Subscribe to get the hand picked best stories every week

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox