What the Russian Orthodox Church can teach the West

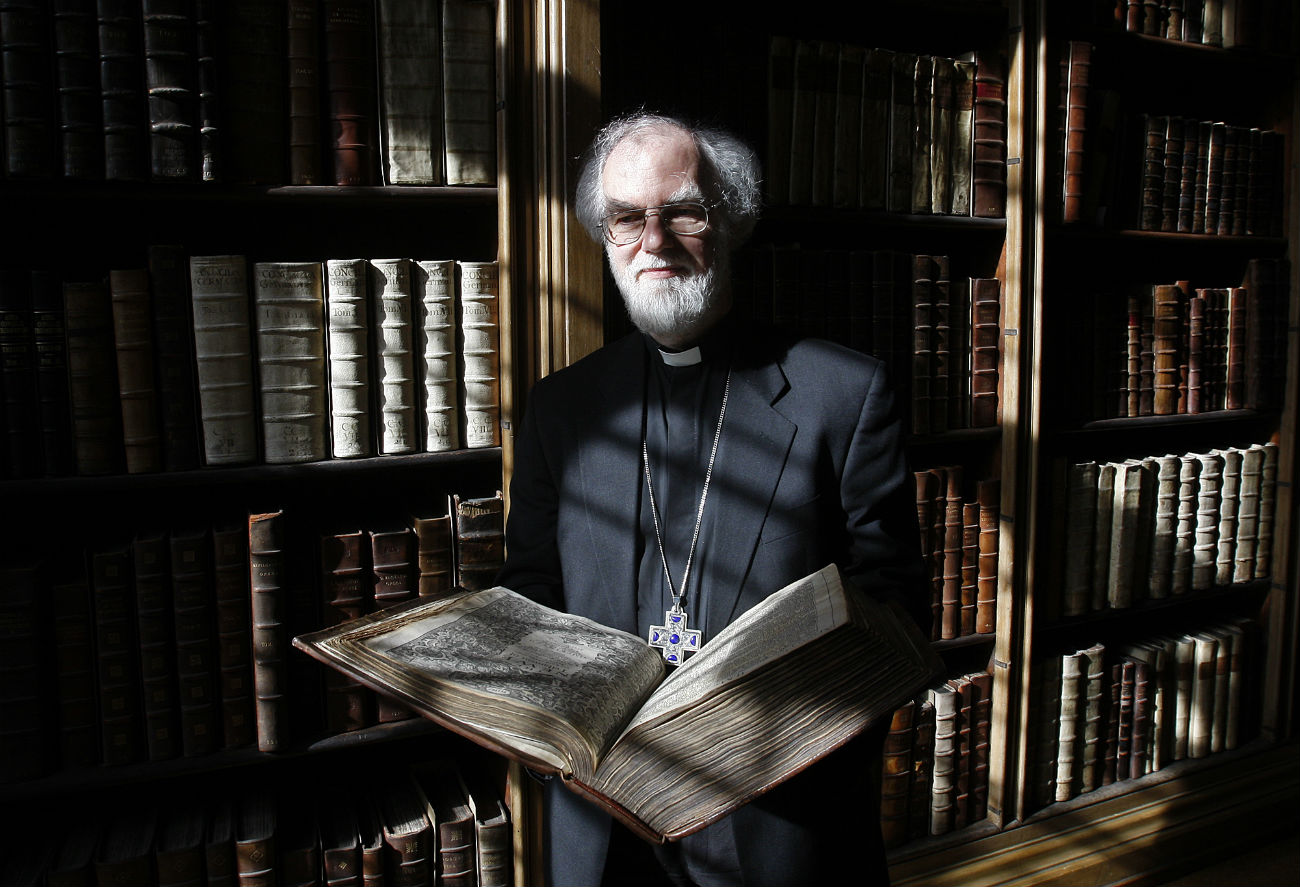

The Archbishop of Canterbury Dr. Rowan Williams.

APTalking in his study - a book-lined room dotted with gold-backed icons in Cambridge University's medieval Magdalene College, where he is currently Master, Williams speaks of the influence Russia has had on his life.

Staring down from one wall there is the peaceful face of St. Seraphim, one of Russia’s most famous and popular saints. The saint, like former archbishop himself, has white beard and wise, compassionate expression. A poet and theologian, Williams is unflaggingly interested in diverse cultures and ideas and says the Russian Orthodox tradition has been crucial to his spiritual life. The Russian influences he cites range from the music of Modest Mussorgsky to Eugene Vodolazkin’s novel Lavr, which only appeared in English (as Laurus) in 2015.

Powerful images

What sparked this lifelong interest in Russia? It began as a teenager, says Williams. He remembers watching Sergei Eisenstein’s film Ivan the Terrible: “I became aware that here was a fascinating, alien cultural presence,” he says; “here was something I wanted to research further.” His postgraduate thesis was on Russian philosopher and mystical theologian, Vladimir Lossky, a leading 20th century religious thinker; Williams had access to transcripts of Lossky’s talks and a handwritten wartime journal.

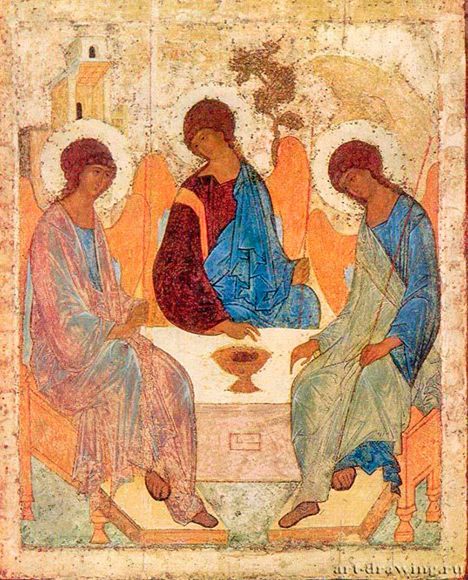

As a teenager, Williams had also read Russian novels, listened to Russian composers and owned a little paperback with reproductions of icons that he found mesmerizing. “How you pray with an icon,” he explains, “is quite different from how you pray with a western picture or a statue.” The arrangement of the figures in Andrei Rublev’s “Trinity” (an image that has had an enduring influence) means the viewer becomes a fourth person at the table, joining the three angels (representing the Holy Trinity) in their deeply symbolic gathering. At the end of a poem in which he imagines the icon painter talking to God, Williams writes: “We shall sit and speak around/ one table, share one food, one earth”. Part of the appeal of Orthodoxy, he says, is that it is not a religion confined “purely to the liturgy and the church”. In Russian Orthodox theology “every domestic act is liturgical, every household ritual”.

Rublev’s famous Trinity icon, 1411 or 1425-27. Source: Press Photo

Rublev’s famous Trinity icon, 1411 or 1425-27. Source: Press Photo

Williams has only himself been to Russia once, in 2003 for the anniversary of St. Seraphim’s canonization. The trip was “intense” with impressions and conversations; he remembers “the river, the riverbank and the overwhelming statue of St. Seraphim at prayer.” The icon of the saint on his study wall was painted for him personally in a Russian convent. 2003 also saw the publication of a book by Williams about icons of Christ; looking at one of these images is to be in “the presence of one … who gives us the power to see all things freshly.”

Dostoevsky’s icons

Rowan Williams. Dostoevsky: Language, Faith and Fiction. Continuum, 2010. Rowan Williams. Dostoevsky: Language, Faith and Fiction. Continuum, 2010. |

Among the forty-odd books Williams has written in as many years, is a book about the novelist Fyodor Dostoevsky, subtitled Language, Faith and Fiction. In it, he argues that: “The writing of fiction can itself be a sort of icon”. He explains that Dostoevsky explores “the Orthodox idea of the image of both true and false sainthood”. For the novelist, imagination is truth and, in his “tensely-worded dialogues”, Dostoevsky explores “what it is that human beings owe to one another”.

Williams writes at length about Devils and he says Stavrogin’s confession in the novel is “one of the most horrifying things I have ever read.” Dostoevsky’s themes, as Williams outlines them, sound more relevant than ever: Terrorism, child abuse, fragmented families, the future of liberal democracy, the clash of cultures and the nature of national identity. Williams quotes the novelist’s famous words about faith: “My hosanna has been formed in the crucible of doubt.”

Language and literature

Williams began to learn Russian as a student and has since translated poems and modified or annotated published translations of Dostoevsky. He was born in 1950 in Swansea (and hopes to return to Wales when he leaves Magdalene in three years) and his family spoke Welsh; his theological studies meant learning several languages and he also translated, from French, Pierre Pascal’s The Religion of the Russian People, a book that helps explain how Christianity continued to thrive as “a living and vital force” in Russia even during the officially-atheist Soviet era.

Although Dostoevsky has been the focus of his literary criticism, Williams has read many other Russian authors (“and returned to them many times”). One of his poems describes Tolstoy’s final days at Astapovo railroad station. Some of Tolstoy’s novellas, like The Kreutzer Sonata, have been disturbing and memorable; he mentions the 1890s short story “Father Sergius”, which describes someone who “very nearly but not quite achieves holiness”, building up an “intense spiritual persona” only to reveal its emptiness.

Greatest novel

Mikhail Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita is, Williams says, “the greatest novel of the twentieth century”; in it, “the sacred world – both diabolical and divine – breaks in at right angles into Stalin’s Moscow”. The devil and a giant cigar-smoking cat arrive in the city, but Jesus and Pontius Pilate also enter this extraordinary novel. “Make of that what you will,” smiles Williams. Are these works equally important in the contemporary world? Absolutely! “One of the most significant things a great novelist does is to force us to inhabit a world that is not our own.”

Eugene Vodolazkin. Laurus. Oneworld Publications, 2015 Eugene Vodolazkin. Laurus. Oneworld Publications, 2015 |

Williams’ knowledge and appreciation of Russian literature does not end with the Soviet era. Vodolazkin’s Laurus, a bestselling novel about the life of a 15th-century Russian monk, was central to his recent talk on the “tradition of holy fools”. He sees the parallel traditions of faith as mutually beneficial, but distinct: “Russian Christianity is what it is because of the Russian history (and so is western Christianity)”. But he insists that: “Learning from Russian Christianity has been one of the most important aspects of my inner life.” And literature, in the Russian mold with a theological underpinning, remains crucial: “In a political world which is beyond satire,” Williams asks, “how do spiritual voices find a hearing?”

Read more:

How to read and comprehend a Russian icon

Metropolitan Anthony of Sourozh: London’s holy Russian inspiration

Orthodox Russian London

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox