The basics of the best Russian drinking toasts

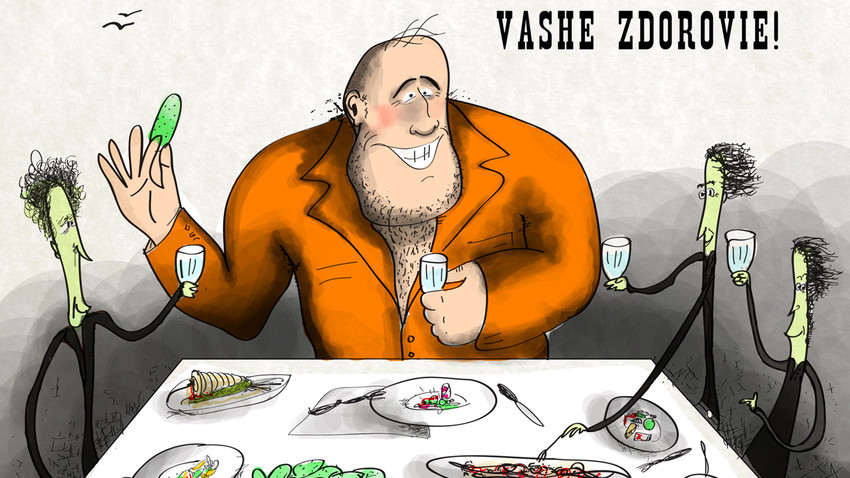

People in other countries usually think that the standard Russian toast is “Na zdorovye!” (literally, "To health!"). That is not exactly right. When pronouncing a toast, Russians are more likely to say "Vashe zrodovye" or "Tvoye zdorovye!", which means "To your health!", depending on the form of address.

Strictly speaking, however, this is not a proper toast. A classic toast has a more complex structure. It usually takes the form of a short story or anecdote, followed by a jocular or paradoxical conclusion, with an invitation to drink in affirmation of that conclusion.

Shurik, the protagonist of the hit 1960s Russian comedy “The Caucasian Prisoner,” comes to the Caucasus to collect local fairy tales, stories, legends and drinking toasts. Every person he meets there offers him a toast for his collection.

Here is one example: “My great-grandfather says, ‘I have a wish to buy a house, but I have no means; I have the means to buy a goat, but I have no wish.’ So let us drink to having all our wishes match our means!” A full glass of wine must be drunk to the bottom after every toast, because “a toast without wine is like a wedding without a bride!”

Yet another longwinded toast from “The Caucasian Prisoner” concludes as follows: "And so when the flock of birds headed south for the winter, one small but proud bird said, I will fly straight to the sun! She flew higher and higher, but very soon she burned her wings and fell to the very bottom of a deep gorge. So let us drink to this: let not a single one of us ever break away from the collective, no matter how high he flies!"

Shurik, who is totally wasted by that point, starts to cry. “What is it, my friend?" his host asks. “I’m so sorry for the bird!” Shurik replies, his eyes full of tears. "I'm so sorry for the bird!” has been a popular catchphrase in Russia for half a century; it is often used to break tension or make things sound a bit less formal and serious.

A traditional Russian drinking party usually includes a sequence of several standard toasts. At a birthday party, the first toast (with wishes of health, success and a long life) is usually to the birthday boy or girl.

The second toast is to their parents. At a wedding, the first toast is “To the health of the newlyweds.” After that, the guests shout “Gorko!” often and loudly, all through the banquet. “Gorko” literally means "bitter” in Russian.

By yelling that the food on the table is bitter, the guests are inviting the newlyweds to make it sweeter by giving each other a sweet long kiss. As the bride and groom kiss, the guests count the seconds: “One, two, three, four, five..." until the kiss is over, whereupon they raise their glasses in a toast.

At a funeral banquet, the first part of the toast is usually an uplifting or touching story about the dearly departed; it is concluded with the words “Vechnaya pamyat” (Let him/her be remembered forever), or “Zemlya pukhom" (Let the ground in which he/she rests be like goose down). When people in Russia drink to the dead (not only at funeral banquets) it is customary not to clink glasses.

A Russian party that is thrown without any special occasion, for no other reason than to have a good time with friends, also involves several standard toasts. The first one is usually “Za vstrechu!” (To our meeting!).

To make sure that the party gets into the mood as soon as possible, the second round of drinks is downed very shortly afterwards, with the toast “Mezhdu pervoy i vtoroy pereryvchik ne bolshoy!", meaning something like "No long breaks allowed between the first and the second rounds!"

The subsequent toasts are usually short, such as "Nu, vzdrognuli!”, “Nu, poehali!”, or “Nu, poneslis" (all variations of “Here we go again”).

Towards the middle of the party someone usually proposes a toast “To beautiful ladies!” or “To the ladies present here!" At this point someone else usually says that real men stand up when they drink a toast to beautiful ladies, and they drink to the bottom. All the gentlemen present promptly comply.

Many years ago it was considered good manners (and a sign of manliness) to drink to the bottom after every toast. These days, such inordinate gulping of spirits is considered to be in bad taste. Nevertheless, the glasses are usually topped up after every toast – this is called “osvezhit” (refresh) in Russia.

Another customary Russian toast is “Za sbychu mecht,” an intentionally twisted and mispronounced version of “Za to, chtoby sbyvalis mechty” (Let our dreams come true), and a way of poking fun at government propaganda slogans.

In the 1980s a book by Mikhail Bulgakov, “Heart of a Dog,” was turned into a film. One of the characters, Sharikov, pronounces an absurd toast, “Zhelayu, chtoby vse!” (I wish that everyone), which immediately became very popular. Incomplete and meaningless, it somehow emphasizes the ritualistic nature of all toasts.

A character from another Soviet film, “Rain in July,” uses another phrase as a toast: "Vsego khoroshego!" (All the best). “Does that mean you are saying goodbye to us?” asks one of those present. “No,” the character says. “I am just saying, All the best.” (The word play here is that "All the best” can in fact be used as a way of saying goodbye.)

The last toast, “Na pososhok", is usually pronounced when the guests are about to leave. In olden days, travelers used a walking stick, called posokh or, diminutively, pososhok in Russian, during long journeys. A toast to the walking stick, therefore, is meant to make sure that the return journey is safe.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox