Since the mid-2000s, Russia has been an increasingly prominent player in the global Internet. It is currently number six in the world in terms of online population, ahead of Germany, the U.K. and France. Russian comes in second among the languages used on websites. The country has several e-businesses valued at over $1 billion, the most famous of which is Yandex, the only non-Asian search engine holding its market leadership against Google.

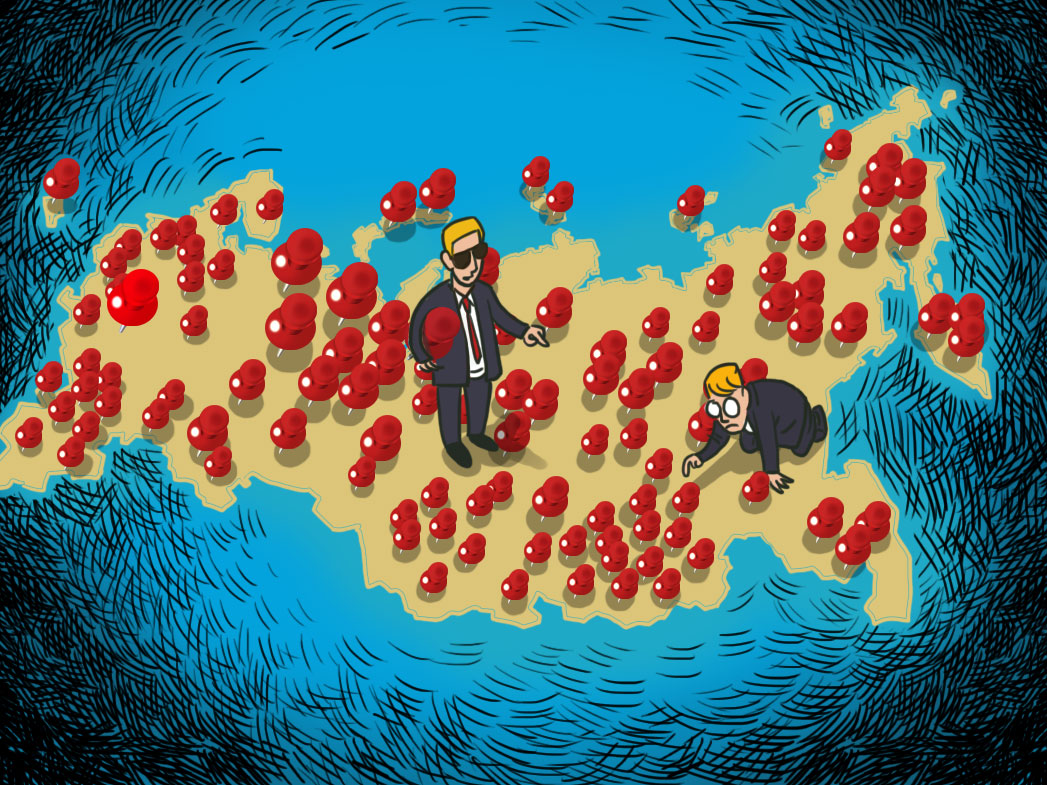

Yet most of the online achievements of Russia are associated with companies headquartered in the capital, Moscow, or — in a few instances — in St. Petersburg, the country’s second city. There is a high degree of business centralization in Russia. The per capita gross regional product of an average region is about 30 percent that of Moscow. Does the same pattern apply to e-businesses in Russia? Are the two capitals really way ahead of other cities and towns?

To study this phenomenon, the Moscow School of Management-Skolkovo undertook a project aiming to research Russian regional online life at both the qualitative and quantitative levels.

We developed the Digital Life Index methodology, which measures the demand for and supply of digital services in 15 Russian cities, which have a population of over 1 million. We looked at seven areas, where digital services are required: transport, finance, retail, healthcare, education, media and public administration. We also studied individual cases of commercial and non-profit digital projects from the Russian regions.

The key outcome of the research was that there is a vibrant digital life across Russia — at least in the big cities. Actually, Moscow came in third on our Index measurement, and even St. Petersburg is only No. 2. The industrial capital of the Urals, Yekaterinburg, tops the list, and No. 4, Perm, is from the same geographical area.

The supply side of digitalization correlates highly with the economic development of a region: the greater its economic activity, the more digital initiatives are launched locally.

On the one hand, this is a fairly predictable finding. After all, digital start-ups need economic resource in order to be launched. On the other hand, much has been said recently about the capability of digital technologies to boost the development of less-resourceful regions by providing direct connectedness to global markets. We don’t see much of this in Russia yet. Interestingly, digital demand — people seeking for digital delivery of traditional services — shows little connection to economic indices, but correlates strongly with the integral quality of life, which includes such “softer” measures as the ecological situation and social cohesion.

This finding is truly important. The demography of Russia — with its overall long-term declining trend — pushes regions into strategic competition for human capital. Moscow has a sort of unfair advantage in the game, with its heavy concentration of economic, administrative and business power (18 out of the top 20 Russian companies are headquartered there). It is vitally important for the regional centers to find ways to stay competitive and keep their most entrepreneurial residents — and attract new ones. The degree of digitalization seems to become an important factor in this.

The more vibrant and diverse the digital life of a region is, the more likely it is to enhance the overall perception of the quality of life. An example is provided by public healthcare, which is traditionally a problematic area, especially in the regions.

The government invested enough capital into hospital hardware, yet attracting and keeping young, motivated and enthusiastic doctors is a much more challenging task. We were quite surprised to find out that healthcare is one of the more digitalized industries in our index – and the one with a comparatively balanced supply and demand.

A string of regional projects emerged, like MedRoom from Novosibirsk or thebestdoctors.ru from Nizhny Novgorod, somewhat resembling Zocdoc.com from the US (though the Russian healthcare system is vastly different).

Another important area of digitalization is finance — in Russia just as elsewhere on the globe. There is a lack of available, high-quality professional services. Small businesses cannot afford a full-time bookkeeper, but the part-time solutions bring risks. This may be ruinous for a business due to the substantial penalties for missing the tax reporting dates or misrepresenting the figures.

Thus a mid-sized bank from Yekaterinburg, bank24.ru, decided to go fully on-line and offer what was effectively “cloud accounting.” The story developed into a business-thriller when the banking regulator decided this service could be used for money laundering and revoked the bank’s license.

The service was obviously in huge demand and met the important goal of developing regional small enterprises. Yet there were strong compliance challenges in the back end, which had to be dealt with.

The business thriller had a happy ending. The Yekaterinburg bank was acquired by a major national financial group, which promised to develop the digital service as an independent line-of-business, while at the same time looking after the back-end compliance issues.

The digital boom is spreading across Russia and making life easier for people in the regions. Pugovitsa from Voronezh specializes in food deliveries, while Dnevnik from St Petersburg provides online school records for parents. Etransport, which is based in Yekaterinburg, is developing artificial intelligence software that suggests public transport options for commuters based on their real-time location.

There are important challenges for regional online businesses in Russia. The system of venture funding across the country is thin at best. Many of the described projects were gathering initial funds from friends and relatives in the absence of professional providers. There is a brighter side to the issue though: the small Russian on-line start-ups from the regions have no other way to survive but to go cash positive in operations as early as possible. Thus, they often come unexpectedly strong on economic model compared to their international peers who have deeper pockets of investors’ money.

The Russian regions may not expand that quickly, preferring to get deeply entrenched on their home turf. However, a single Russian region can have an economy equal in size to that of Slovenia, Bolivia or Cyprus. Having a strong local grip in such circumstances can be quite a solid strategy.

Vladimir Korovkin is the head of innovation and digital research at Moscow School of Management-Skolkovo

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox