Capitalism for the communists: How the USSR penetrated the U.S. arms industry

Boeing B-17E in flight, 1942. Source: U.S. Air Force

As the Soviet Union emerged from the Civil War in 1922, the country literally lay in ruins, and its army in tatters. The military industry in tsarist Russia had been far removed from its European counterparts to start with: While able to build a battleship or issue each soldier with a rifle in peacetime,the First World War had showed this to be the extent of Russia’s capacity. And the sector’s remnants in the early 1920s left little to build on. Instead, the Soviet Union had to look elsewhere.

While the Red Army had increased in numerical strength over the civil war years, its arsenal was still roughly on a par with the neighboring countries, and certainly not befitting of any leading military power.

The only solution was to completely rebuild the country’s military industry, which lagged far behind the West in technology and design capacities. While the Reds and Whites butchered each other in Russia, the Europeans conceptualized and developed the experience of the First World War to create a new era of military technical prowess. Nobody was in a hurry to share this knowhow with the Bolsheviks.

By the end of the 1920s, the Soviet economy had recovered enough to allow the government to allocate funds for overseas purchases of military equipment. And as Europe and the United States plunged into the Great Depression in 1929, Russia’s gold became very useful to them.

Shady deals and fly-by-nighters

Since the Soviet Union had no diplomatic relations with many countries in the West it had to open private firms to conduct trade. The Arcos trading corporation worked with Britain while Amtorg dealt with the United States for the Soviet government, coordinating all aspects of technical cooperation from the identification and selection of military equipment to trips by Soviet engineers to U.S. manufacturing plants.

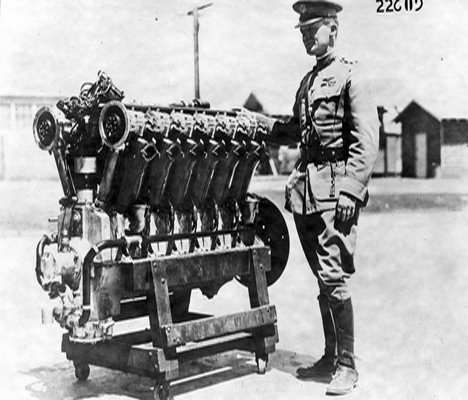

Above all, the country needed U.S. aviation technology. In 1922, the Soviets got their hands on a Liberty aircraft engine, known for its reliability and quality of construction. The decision was made to copy it and start mass production at a Moscow plant, but one sample was not enough. The mass of accompanying technical documentation, spare parts and other aspects of such a project were also missing, so the task of gathering the wherewithal was passed to Amtorg, along with $1.5 million for acquisitions, a huge sum at the time.

The first Liberty V12 engine. Source: nationalmuseum.af.mil

But while their purchasing coffers were full, Moscow’s envoys were faced with a major barrier of mistrust towards their efforts, since any venture or company that involved the Soviets immediately engendered great suspicion and reluctance to sell large consignments of equipment. Therefore Amtorg had to quickly master some unfamiliar capitalist ruses, including the organization of shell companies and fly-by-night ventures that would pop up and do their business for them. The first batch of Liberty engines and 350 ignition units was acquired through the "Zaustinsky Office,” a specially established front company. However, it only took a few years until direct business channels were opened and there was no further need for such shadowy entities.

Profiting from the Great Depression

Tons of cargo came to the USSR via Amtorg, transported by a special freight service founded by the People's Commissariat of Foreign Trade. In 1925 alone, the company purchased aircraft instruments worth $400,000, accompanied by containers full of books, blueprints, albums and brochures from U.S. plants. In 1929, a Soviet Air Force officer arrived in the United States tasked with studying facilities for making parachutes, which were virtually unheard of in his country. The Soviet guest was not only shown how they were made but even offered the chance to make a test jump himself. The officer was so inspired by the experience that he returned home and zealously promoted parachutes, eventually creating the first airborne military unit.

At first the Americans were reluctant to discuss the sale of whole aircraft to the Russians, but the economic crisis of 1929 forced them to make concessions. In 1934, Soviet delegations began to arrive in the U.S. and buy interesting examples of equipment and technology, under the supervision of prominent civil aircraft designer Andrei Tupolev and also Mikhail Gurevich, who went on to design the MiG fighter. In just 1936 the Soviets bought and flew home a DC-3 transport aircraft, flying boats and amphibious aircraft samples, and even one ground attack aircraft. The envoys also very nearly got their hands on the jewel in the crown of the U.S. aircraft industry, the B-17 “Flying Fortress” heavy bomber, used in their thousands against Germany and Japan in the Second World War, but the prize finally eluded them.

Unlike U.S. tanks purchased through the same channels, none of these samples went into production. However, many of their best elements were incorporated in the design and mass production of some of the most prolific Soviet military aircraft.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox