How a winemaker from Russia made Californian wine world-famous

On June 7, 1976, Time Magazine announced the results of the Paris Tasting: a panel of distinguished judges ruled two wines from California had surpassed their French competitors — something unheard of at a time when Californian wines were generally discarded by wine lovers.

Little did they know that the wine’s creator was a Russian, who came to California with the sole purpose of creating the best wines in the U.S. and in the entire world.

A war lost

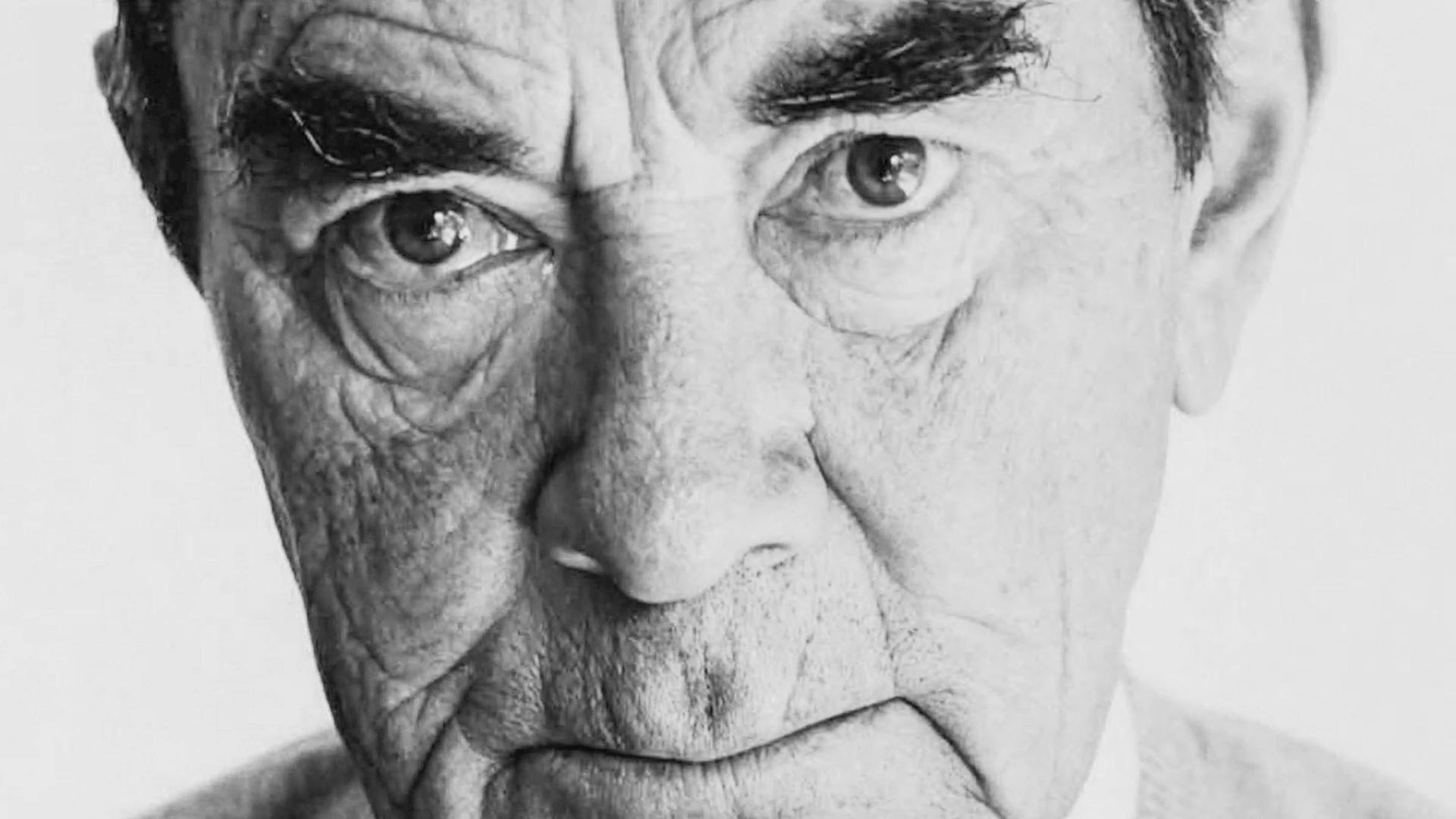

André Tchelistcheff — the man behind the two winning lots — is a man of tragic, yet grand, fate. His life is the epitome of the turbulent years of early 20th century Russia.

Born in 1901 into a noble family on a family estate near Kaluga, Tchelistcheff enjoyed all the delights of the noble upbringing: life on the estate, gymnasium studies in Moscow, intellectual and social gatherings in the capital. A son of the Chief Justice of Tsarist Russia’s Supreme Court, young Tchelistcheff’s future would have almost certainly been perfectly structured hadn’t the Russian Revolution happened in 1917.

After the Russian Revolution, Tchelistcheff’s noble family became one of the Bolsheviks’ primary targets.

Getty ImagesThe well-known noble family became one of the Bolsheviks’ primary targets: Tchelistcheff’s estate was attacked and destroyed. Their hunting dogs were hung up on the trees that led to the estate, yet the family was able to flee thanks to Tchelistcheff’s father's extensive connections.

Young André secured his father’s permission to join the White Army and was dispatched to fight the Reds in Crimea. Wounded, Tchelistcheff miraculously survived, thanks to a Cossack soldier who threw his unconscious body over his horse and brought him to safety.

After the final defeat of the White Army in the Russian Civil War, André fled Russia with other troops. He worked as a miner in Bulgaria before he had a chance to begin agricultural and viticultural studies at the Brno University in Czechoslovakia, in spite of his initial inclination to study medicine.

André Tchelistcheff, Rock Hudson, Jean Simmons, Marquise De Pins.

Legion MediaGraduating from the Brno University, André proceeded to study microbiology and fermentation at the Institut National Agronomique and at the Pasteur Institute in France.

The choice of the subject proved to be fateful.

Prohibition business

In the 1930s, the Californian wine-making industry was in a state of severe decay after thirteen years of prohibition in the U.S. Some wineries resorted to producing tobacco additives to survive, which damaged the foundation upon which great wine-making could be built. In the aftermath of the prohibition era, sweet wines were in the greatest demand among unsophisticated American wine drinkers.

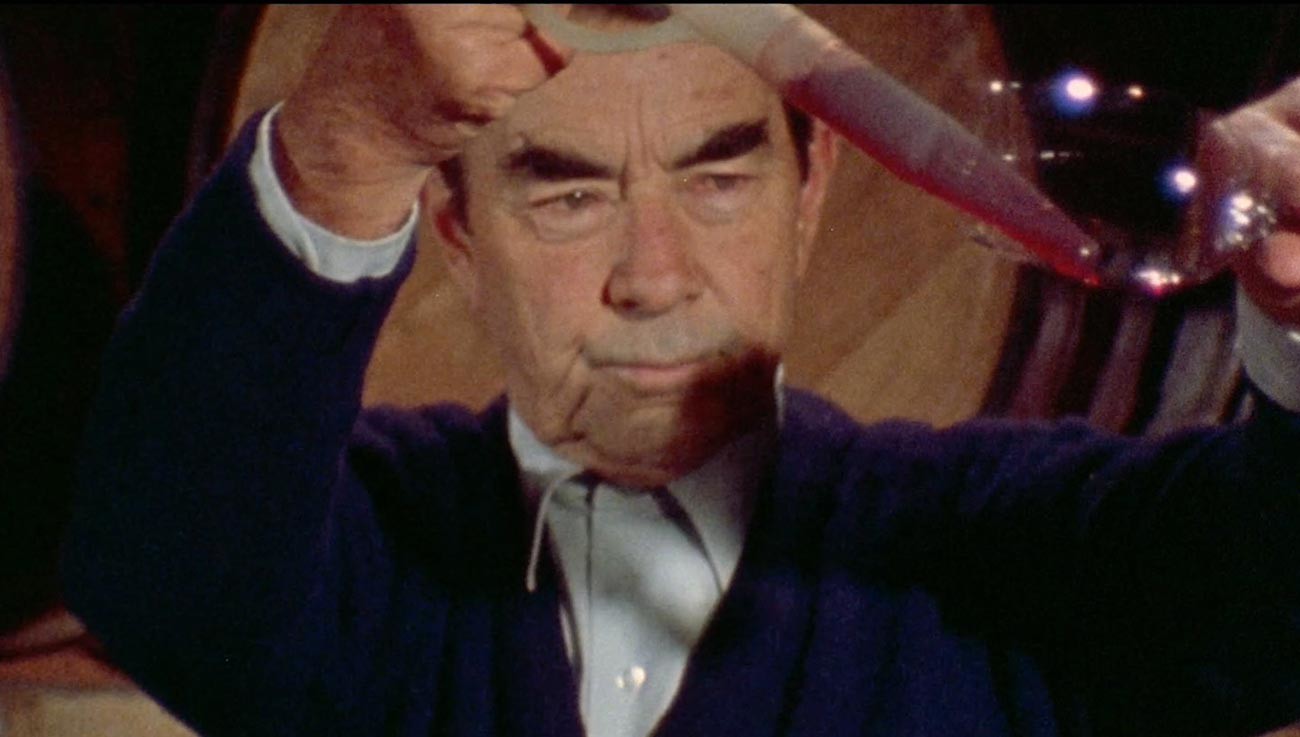

Winemaker André Tchelistcheff.

Getty ImagesThe California wine-making industry was dominated by a man named Georges de Latour. A native of France, de Latour came to the U.S. in 1883, purchased acres of land and a house in Napa Valley, California, and began planting fine varietal grapes including Cabernet Sauvignon, Pinot noir, Gray Riesling and others.

Fortunately for the French, his vineyard and connections in the wine-making world only solidified during the prohibition as he acquired a strong backing of the Catholic Church, to which he supplied with wines for sacramental ceremonies.

Professor Paul Marsais at the Pasteur Institute pointed out his best student to de Latour: a Russian named André Tchelistcheff.

Legion MediaIn 1938, after the repeal of the prohibition in the U.S., a 78-year-old de Latour returned to his native France in search of a winemaker who would take his successful vineyard to a whole new level.

Professor Paul Marsais at the Pasteur Institute pointed out his best student to de Latour: a Russian named André Tchelistcheff.

The new life in California

Impressed by the wealthy and influential wine-maker — “a gentleman impeccably dressed with a beautiful London made suit, polished fingernails, with an expression of tremendous self-confidence and self-respect” — Tchelistcheff accepted de Latour’s offer and moved to California.

Tchelistcheff accepted de Latour’s offer and moved to California.

Getty ImagesIn Napa Valley, Tchelistcheff was unpleasantly surprised by the unsophisticated process of wine production compared to France, where he had studied.

“At Beaulieu, he was shocked at the high temperature of the cellars. He went from barrel to barrel, finding the dessert wines acceptable and the dry wines poor. The winemaking processes were primitive at best. Many of the grapes being used were high yield, coarse varieties. He found careless chemistry and vinegary wines. The tiny, rudimentary laboratory shocked this meticulous researcher accustomed to the experiments and controls in France where the technology, although very commercial, was also very exacting,” wrote Tchelistcheff’s grand nephew Mark about his uncle’s first impression of the Beaulieu, the famous de Latour winery.

Tchelistcheff pioneered viticulture in the U.S.

Legion MediaThe extent of Tchelistcheff’s effort to reinvent the Californian wine is hard to overestimate: the Russian introduced cold fermentation of whites and rosés, pioneered control of malolactic fermentation in reds. On top of that, he initiated a total replacement of outdated pipes, valves, and pumps to eliminate high metallic concentrations in the wines.

Tchelistcheff pioneered viticulture in the U.S., helping American wine-makers to identify areas in their country that were best for cultivating certain kinds of grapes: he recommended that Pinot Gris be planted in Oregon and Cabernet Sauvignon — in Washington State.

The Statue Of Wine Pioneer André Tchelistcheff.

Legion MediaTchelistcheff retired from the now world-famous BV — the Beaulieu Vineyard — in 1973 at the age of 72. Being an accomplished expert, decorated with multiple awards in the wine-making industry, Tchelistcheff moved on to consulting and fostering a new generation of American wine-makers.

Among others, Tchelistcheff mentored MaryAnn Graf, the first female winemaker in the U.S. Once during an interview to Wines & Vines Magazine Graf offered an anagram that she said described Tchelistcheff best:

Articulate, Ageless

Naughty

Democratic, Debonair

Resourceful

Energetic, Ebullient

Tireless

Compassionate

Handsome

Enthusiastic

Logical

Intellectual, Impish

Serious, Suave

Tyrannical

Charming, Complex

Hardworking, Honest

Exacting

Frank

Fascinating

“He is missing the letter ‘G’ for Gentleman – always,” she finally added.

Click here to read about a Tsarist military officer who became a general in the U.S. Army.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox