A ‘Brexit’ could see British policy on Russia sharpen

Is the ‘Brexit’ possible?

ReutersWhat are the benefits and the shortcomings of the theoretical filing for divorce with the EU by Britain? The shortlisted arguments provided for RBTH by Moscow-based experts on the UK and the challenges of the current discontent all across Europe amount to a concoction of apathy, a feeling that it matters less now than it did before sanctions, and hopes that “enlightened self-interest” and pragmatic calculations would eventually triumph.

The main considerations revolved around the competitive advantages offered by the City as a reputed international financial hub. It was an acknowledged fact that the banking moguls of the City focus most of their business activities on transatlantic operations, and often do not consider themselves as being part of Europe. This has certain benefits for Russian banks and financial institutions dealing with partners on both sides of the Atlantic.

This was probably one of the main attractions of London for Russian investors in terms of economic engagement. Russian portfolio investments and asset management previously conducted in the City were no less rewarding since the British financial sector accounts for 14 percent of GDP (unofficial figures claim it is up to 30 percent of GDP). Now, however, the Russian circus has left town in a search for a more comfortable environment where profit-seekers feel their wealth is not at risk of potential expropriation.

The neither/nor dichotomy

So, should Russia be wary or, on the contrary, enthusiastic about Britain parting with the EU, a so-called “Brexit”? Basically, the reply by Kirill Koktysh, Associate Professor at Moscow State Institute of International Relations, who talked to RBTH, amounted to a single-liner: “Neither!”

“Actually, it would have made a difference some two years ago and earlier. Not any longer. London is not a formidable manufacturing center and not a huge commodity trading platform. It is a financial hub. Russian financial institutions used to be keen to use the City as a gateway to the U.S. and global markets.

“However, right after Prime Minister David Cameron did not exclude ‘expropriation,’ meaning the seizure of assets of Russian companies, they have withdrawn their capital and moved to safer and more comfortable places, like Shanghai. A similar threat coming from London that Russia should be deprived of the use of SWIFT as a vehicle for transactions led, first, to seeking an alternative (it has been found), and, second, to pass the verdict on the City: It is an inhospitable place where the rules of ‘fair play’ do not apply.”

– Brexit or no Brexit, is the Russian business and political elite likely to be unimpressed and remain indifferent?

“In fact, there is no place for indifference in this case. It matters. But as for changes, especially in terms of foreign policy, Moscow will act on the premise that bilateral relations with Britain are dependent on the state of play in its interaction with Washington.”

Pinning hopes on enlightened self-interest

Without contradicting the main message of Kirill Koktysh, Yelena Ananiyeva, head of the Center for UK Studies at the Russian Academy of Sciences’ Institute of Europe, added some crucial nuances while providing her insight into the intricate matter for RBTH.

“Until now, Britain has fit well into the derogatory forecast made by French president Charles de Gaulle that if admitted to the then EEC (now EU), Britain would act as a U.S. Trojan Horse. The Obama administration made no bones that ‘a strong’ Britain within a strong Europe is in the best U.S. national interests, meaning that the UK should remain a member of the EU. All throughout recent history, Britain has sided with Poland and the Baltic states in promoting and pursuing EU policy detrimental to Russia.”

– To what extent was it “detrimental”? What do you mean?

“The UK, together with Poland and Lithuania, stood for imposing sanctions on Russia at the extraordinary EU summit (Sept. 1, 2008) following the Georgian crisis, but failed that time. The UK was at the forefront when EU sanctions were imposed on Russia in 2014 following the Ukrainian crisis, to mention just these two occasions.”

– So, will this type of unfriendly policy be reversed should Brexit happen?

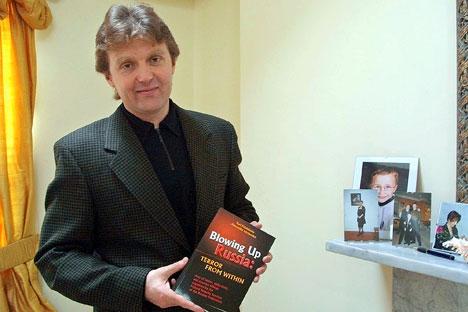

“Personally, I doubt it. However, I suggest examining the records. When the 2008 financial crisis hit the British economy hard, it was to Moscow that Peter Mandelson [after being appointed Business Secretary by Prime Minister Gordon Brown] paid his first visit abroad to promote trade and investment with Russia. It came in the wake of the ‘Litvinenko case” in 2007 and Russia’s ‘compulsion to peace’ operation [the term used by the Kremlin – RBTH] in response to Georgia’s aggression against South Ossetia in 2008.

“Then again, one might have forgotten, David Cameron made a trip to Moscow in 2011. The 2+2 consultation mechanism involving ministers of foreign affairs and defense was launched. Other measures of a positive engagement to turn a page in bilateral relations were undertaken. It all ended abruptly with the start of the Ukrainian crisis.

“Yet these examples are evidence of a pragmatic approach to choosing friends and foes. This is familiar to British policymakers.”

– How does this relate to the possible “reset” in Russia’s turbulent relationship with Britain if it chooses to sail alone?

“In theory, Britain can no longer ‘sail alone,’ it will have to lean on someone. And this ‘someone’ would be most probably the United States, which will inevitably translate into a more pro-American foreign policy with its well-entrenched anti-Russian phobias. Even if the UK decides to remain in the EU as result of the referendum in June, the anti-Russian rhetoric will not stop, keeping in mind the future vote in the UK parliament on the modernization of Trident [the UK’s nuclear submarine program – RBTH].”

Having said this, I would once again warn against underestimating the ability of the British ruling elites to think and act pragmatically. To recall the famous words of Lord Palmerston: ‘We have no eternal allies, and we have no perpetual enemies. Our interests are eternal and perpetual, and those interests it is our duty to follow...’”

EU softens UK to its benefit

So far, British strategy-makers have had to accept the legal and moral framework of the 28 nation states’ consolidated policies. This invariably means making sound compromises when it comes to political and economic interaction with Russia.

The divergence of views among EU nations on the long-term expediency of alienating let alone demonizing Russia prevents London from making erratic and irresponsible moves out of its longstanding antipathy toward Moscow, which has been a hallmark of relations between the two for more than just the last 15 years.

EU collective decision-making is rooted in finding a common denominator, which sometimes tends not to follow the best practices when dealing with Russia. Yet this procedure relatively softens the bellicose instincts of the East European recruits.

Without the EU system of checks and balances, any nationalist-prone government in London would be free to entertain unsafe methods of conducting foreign policy. It would not help patch up quarrels with Moscow and start a new chapter focused on promoting cooperation rather than fighting the Cold War anew.

Unlike the well-known Gustave Le Bon maxim that a crowd is frequently more aggressive than most individuals in the group, in the case of a Brexit the regional island superpower would not necessarily embrace a pacifist agenda and go for a “reset” in relations with Russia.

For Moscow, the UK voting to remain within the framework of the EU would matter in the context of its foreign policy priorities. Whenever the European Union performs, voluntarily or involuntarily, the role of a pacifier and moderator, it should be praised for rejecting ideological short-terminism and embracing long-term geopolitical expediency by calling for a positive and meaningful relationship with Russia.

As part of the EU, Britain simply looks more predictable and responsible as far as Moscow is concerned.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox