Rebelling without a cause

Arslan Hasavov visiting the US with the winners of the "Debut" prize. Source: RIA Novosti.

Searching for a life with meaning and purpose, twenty-year-old Artur Kara visits a series of political groups in Moscow, encountering former prisoners from Guantanamo at the headquarters of the Islamic Committee or literary dreamers among the National Bolsheviks. Unable to find a group he wants to join, he plans his own revolution.

The comic element in Khasavov’s writing rescues it from drowning in adolescent self-absorption. It is unlikely that young writers emerging from western schools of creative writing would dare to make their hero a wannabe-author, but Kara’s opening lines are a fantasy about his future fame as “the writer of brilliant books”; his pseudo-autobiographical admissions are intimate and awkwardly funny.

|

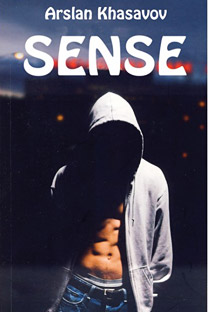

| The "SENSE" cover |

Prolific translator Arch Tait (who has also translated novels by literary-bestseller Ludmila Ulitskaya), brilliantly conveys the hero’s stylistic pretentions, alongside other registers from ideological jargon to celebrity LiveJournal blogs. Tait has commented on Khasavov’s “sense of irony and humor” and his ability to “distance himself from his hero’s social preoccupations and hyperbole.” In many ways, the alienation young Kara feels is the classic confusion of any misfit teenager, quoting Nietzsche and Dostoevsky, struggling to find a place in an uncaring society. The gap between Kara’s ambition and his life provides both comedy and pathos. A poor Muslim boy with a limp, he sees himself as a glamorous revolutionary leader. Sitting in a suburban Moscow park, he reflects on the difficulty of his chosen path, “the path of a Samurai, of an infinitely lonely man who has chosen to be lonely. And here is that man now … finishing what remains of his hot dog.” His manifesto includes principles like using human sewage to heat apartments, or compulsory public nudity.

Kara’s ultimate goal is immortality at whatever cost. He regularly daydreams about his successful future life, where “palaces await me with luxuriant gardens.” At the same time, he is contemptuous of the material aspirations he imagines for the workers in Moscow’s new sky-scraping business complex “package holidays in Goa … high-definition TVs.” They will “buy everything that can be bought,” he says, but always want something more: “If they have a car, they will want a yacht. If they have a wife, they will want a mistress. They will substitute money for God...”

Kara’s new movement, “SENSE,” has a flag whose central emblem is a symbolic red anemone; the etymology of the flower (from the Greek for “wind”) becomes a metaphor sweeping through the rest of the novel into a final poem. One of the book’s many epigraphs is also a poem, by Eduard Limonov, an influential figure both as writer and opposition activist.

In its satirical conviction, “SENSE” is reminiscent of Vladimir Sorokin’s “Ice Trilogy.” Khasavov may not yet have Sorokin’s epic scope or linguistic virtuosity, but the mixture of messianic energy and absurdity has similar political targets and reaches similarly nihilistic conclusions about modern Russia. Khasavov has lived and studied in Moscow, but is originally a Kumyk Chechen who grew up in Turkmenistan. According to the Caucasian Knot newspaper, the writer was attacked in Moscow last year after one of his short stories had provoked the Chechen authorities.

Since writing “SENSE,” Khasavov has produced a highly acclaimed volume of short stories and a new novel about “an ordinary country boy who is gradually drawn into a Jihad war.” Khasavov’s uncomfortable frankness is beyond topical. His dissection of what motivates young people provides a disturbing glimpse of a violent future as well as a raw, but entertaining satire on the present.

“SENSE” was published in 2012 by GLAS publishing house.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox