Daniil Kharms, Master of Deadpan, Father of the Absurd

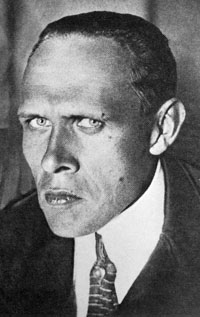

Potrait of Daniil Kharms by Tatyana Druchinina

Grotesque deaths in miniature are a hallmark of the work of Daniil Kharms. In one of his short stories, several women throw themselves out of the same apartment block window, each shattering upon impact. In another, a man dies from eating too much: “One day Orlov stuffed himself with mashed peas and died. Krylov, having heard the news, also died. And Spiridonov died regardless…”

The latter, an absurdist gem, is especially poignant, since Kharms died of starvation in a psych ward of a Soviet hospital during the Seige of Leningrad in 1942. The avant-garde author had been basically imprisoned there for his artistic subversion, and according to absurdist American writer George Saunders, perhaps also "his general strangeness."

|

| Like many artists before and after him, Kharms found a

precarious sanctuary in children’s literature, which was less restrictive and

censored. Source: RIA Novosti |

Finally, seventy years after his death, all of his scribbled short prose, poetry and theater scenes have been deciphered and published. Kharms has been catapulted into the canon of modern literature of Russia and Europe—just like that.

Many view his absurdity as a political seismogram from an evil age. "Incidences", a work replete with chain dances of death, was written in 1936, during the reign of terror known as Stalin's Great Purge. Hundreds of thousands of Soviet citizens were convicted of anti-Soviet crimes, from leading uprisings to associating with known Trotskyites; many died in penal colonies or were executed.

But Kharms is so much more than a "right-place, right-time," writer. He was a playful artist who could be as terrifying as Kafka and as humorous as Beckett.

Born Daniil Yuvachev, Kharms was too late for the Silver Age of literature in St Petersburg. When Kharms founded literary circles such as the “Left Flank” and OBERIU (The Union of Real Art) in the mid-1920s, the Soviet policy on culture and education had already begun to tighten the screws.

“When verses are taken from a page and hurled at a window they should shatter glass,” Kharms once said. An imposing bohemian figure with a stovepipe hat and pipe, he preferred reading his poems aloud. He felt his life and art were the same. “I’m the same as all of you, just better.”

Kharms was first arrested in 1932. His standing within the intelligentsia reached new heights in 1935, when he wrote and delivered the poetic eulogy at the funeral of his friend Kazimir Malevich, the revered suprematist painter and creator of the painting, "Black Square."

Refuge in Children’s Literature

Like many artists before and after him, Kharms found a precarious sanctuary in children’s literature, which was less restrictive and censored. However, his second wife Marina Malitch admitted that he despised children. “It really is inexplicable that despite his utter contempt for children he was able to write such wonderful stories for them. When he would show up to a matinée and perform magic tricks, he held the children in the palm of his hand. In the Leningrad-based publications Yozhik (The Hedgehog), he wrote poetry that was just as ironic and subversive as what he composed for adults.

But the world of children’s literature did not stay safe for long. When he translated Wilhem Busch’s illustrated story “Plish and Plum,” he was ripped apart by critics. “Our children need to know who is a friend and who is an enemy,” one critic said. In 1937, the editors of the Leningrad publisher was the victim of a terror attack. Kharms only managed to earn a few rubles with his children’s books up to the time of his arrest.

Shortly after Nazi Germany attacked the Soviet Union, Kharms was arrested by the NKVD, the secret police and precursor of the KGB. He died on February 2, 1942. His works survived thanks to his friend, philosopher Jakov Druskin, who managed to save a suitcase full of manuscripts from his bombed out apartment.

In the decades that followed World War II, Kharms was published only in Samizdat publications. It was not until the time of perestroika that a few of his works were published. Today his works are accessible to Russian readers and have been translated into many languages, including English. American critics called his work «exhilirating» and even came up with a name for his powers of anti-description, calling it "Kharmsifying."

"So it is in life," Kharms wrote, "a fool through and through and yet he wants to express himself. He needs to be punched in the snout."

"Today I Wrote Nothing..."

Daniil Kharms certainly had the knack for the headline, that quip that encapsulated his mood and the moment within his poems and the shortest of short stories. A new reader might start with the richly translated collection, "It Happened Like This: Stories and Poems (Farrar, Straus and Giroux), followed by "Today I Wrote Nothing: The Selected Writings of Daniil Kharms," (Overlook). A set of miniatures, called "Incidences," received flush praise in The New York Times: “With remarkable precision and fluid language, the stories capture everyday tension in a land where an innocent knock on the door might mean entrapment in a bureaucratic maze or even death at the hands of the military.”

Other works in English offer context for the acolyte, including "The Man with the Black Coat: Russia's Literature of the Absurd" (European classics) and "Oberiu: An Anthology of Russian Absurdism by Eugene Ostashevsky. What are the most important points for new readers? Kharms was witty, charmingly deadpan, cryptic and doomed. But seventy years later, he now has the last word.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox