How Tolstoy wanted to reform Russian education

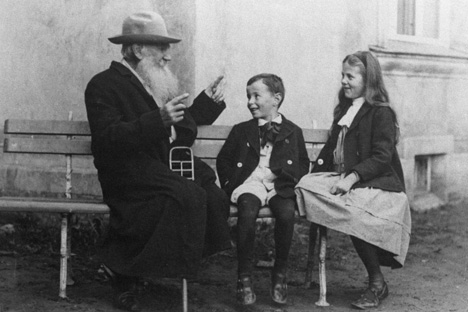

Tolstoy’s educational credo was inquiry-based, experiential, and completely modern. Source: RIA Novosti / Boris Prikhodko

“During the first days of my marriage, servants, serfs and schoolchildren came to congratulate us,” remembered Sofia Tolstaya, wife of novelist Lev Tolstoy.

One can imagine an idyllic scene of children excitedly running toward the couple as they strolled the pastoral lands of the estate: The serfs worked the soil and animals for the Tolstoys, who were landowners, while the servants maintained the manor house. But who were the schoolchildren of Yasnaya Polyana, and why were they so eager to greet the newlyweds?

Related:

A prominent literary critic reveals Tolstoy's mystery

Watch video: Yasnaya Polyana, an orphanage at the Leo Tolstoy's estate

Tolstoy is widely known and adored as a novelist, but less so as a philosopher and preacher. Tolstoy the teacher is even more obscured by time, even though he created a new methodology of teaching literacy and basic knowledge. Tolstoy devised fundamental reading primers, and in these he crammed all the writing he believed essential for children – whether they were the sons of cobblers or heirs to the throne.

This was Tolstoy's most cherished ideal – to unite Russia through the minds of its children.

Tolstoy’s educational credo was inquiry-based, experiential, and completely modern. Rather than coerce them to conform to a rigid curriculum, he wanted children to learn and explore what they found interesting, and beneficial for themselves.

No idea could have been more greatly at odds with teaching methods in Russia's parochial schools in the 19th century. Tolstoy tried to perfect his teaching systems on the children of the Yasnaya Polyana serfs, and other nearby estates where the landlords didn’t object.

The school at Yasnaya Polyana opened in 1859. There was no schoolhouse, so the lessons were held in the gatehouse or Tolstoy's own home. The teachers were students from Moscow, along with Lev Tolstoy himself, and his wife Sofia. Tolstoy also traveled all around Europe to research various methods of teaching.

To this day, visitors to the house at Yasnaya Polyana can see the school supplies, which were astonishingly advanced for their day, even including microscopes. All of it was ordered from abroad, and no expense seemed to be spared. The pupils studied the movements of the heavenly bodies, and the principles of physics, chemistry, mathematics and geography. Naturally, significant emphasis was placed on literature.

Tolstoy compiled three primers, devoting several years of his life to the exercise. Some of the material in them he wrote himself – such as “The Prisoner of the Caucasus,” which went on to great fame, and has been filmed several times. The core material of his primers was folk tales, moral parables, and the Lives of the Saints.

Even so, the schoolbooks failed to meet the Church's standards for this genre. Rather than emphasizing church dogma, the stories capture Tolstoy's teaching style – “the spark of life” rather than “rote learning.”

"When reading the reminiscences of his own children, it appears that Tolstoy created a private corner of heaven on earth. However running a village school for his serf and servants children proved more elusive; the all-consuming nature of the school was not compatible with a young wife and family.

In 1862 Lev Tolstoy wrote to his friend Ivan Borisov. “Our home life is to God's greater glory, and our lives are such, as need not end!” Yet he kissed his last mistress, as he called his education projects, farewell. The laboring children could not work and study. The irony of his experiment was that they needed to be free to go to school. Tolstoy closed the school before he could gain a readership for his educational journal.

Ultimately, Tolstoy’s passion for teaching couldn't be reconciled with the interests of his young wife. The village teachers who came to “broaden their professional experience” at Yasnaya Polyana used to smoke in the living room – and Sofia, who very soon became pregnant, couldn't abide the smell. Tensions between Sofia and Tolstoy’s acolyte students simmered.

“All these young people” Sofia Tolstaya recalled “were perturbed by my presence. Some of them took a hostile view of me, thinking I somehow signified the end of their close relationship with Tolstoy, and that he would throw all his interests into family life instead.” It was the beginning of a long-running feud between Sofia and the students.

“Tolstoy Schools” never caught on in Russia. There are just a handful of schools in the entire country where the approach to teaching can be linked to, or is inspired by Tolstoy. It's remarkable, then, that Japan has several schools that pursue a strict Tolstovian curriculum.

Pavel Basinsky is an author, literary critic, and literary commentator. He is the author of books about Tolstoy – “Lev Tolstoy, The Flight From Paradise” (2010) and “The Saintly Versus Lev” (2013).

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox