The 42nd London Book Fair brings together both writers and publishers as well as readers and translators. Source: Tatyana Rubleva

A series of nearly forty different Russian literary events brought a huge range of readers, writers, translators, editors and publishers to the UK capital this week.

The line-up at the 42nd London Book Fair in Earls Court saw relatively unknown writers alongside bestselling authors like Ludmila Ulitskaya or celebrated translators like Robert Chandler, talking about topics as diverse as prizes, politics and postmodernism.

Novelists, Igor Sakhnovsky, Hamid Ismailov and Anna Starobinets opened the proceedings with a lively discussion on “Who is the Russian Writer?” Oleg Pavlov, Maria Galina and others held popular “in conversation” sessions at the Russian Bookshops on Piccadilly.

Some of the youngest writers at the conference provided a change from the hours of debate with witty readings and even a tune on a “vargan” mouth harp.

Irina Bogatyreva’s impromptu concert brought the free air of the Altai Mountains into the crowded exhibition hall and was as surprising as her uninhibited, hitchhiking travelogues.

“The writer is not me, but someone else,” said Bogatyreva, explaining that she did not feel gender was a conscious issue in her work. “Not a woman, not a man, perhaps a spirit…”

The younger generation is already creating the libraries of the future. What characterizes the work of 32-year-old Alexander Snegirev is its sense of immediacy.

“I always base my stories on the things which are most important for me in life,” he said.

Snegirev’s novel, “Petroleum Venus,” came out in English earlier this year and tells the sometimes comic, sometimes heart-breaking story of a single dad looking after his Down’s syndrome son in Moscow.

Russia Beyond The Headlines at the 42nd London Book Fair. Source: Tatyana Rubleva

“It is a little bit of my own story and that is why I wrote it, not to get tears from my audience," Snegirev said. "I found this experience very strange, destructive and important. I was trying to show all aspects of life, like diamonds where you can see many reflections. You cannot say my life is happy or unhappy."

"It is never totally funny or totally tragic,” he added.

Snegirev talked briefly about the difficulties disabled Muscovites face.

“It’s something special to get real love because life is tough in Russia,” he said. “You never know what will happen in Russia…but I predict that in half a century we will not recognize the country. How it will change, I don’t know, but I’m sure it will be interesting.”

Peter Mayer, veteran publisher and former CEO of Penguin Books, outlined the plans for a 125-volume “Russian Library” in English. The seven-member board will combine Russian experts and foreign professors and will have the tricky task of selecting which books to include from Russia’s thousand years of literary heritage.

“An idea like this doesn’t exist in any other language,” said Mayer. “I don’t believe there has ever been a national library in a foreign language.”

Soviet literature’s passport from Ann Arbor to the world

Peter Kaufman, coordinator of the Read Russia project, said the library would also be “a celebration of the art of translation."

"Without the work of distinguished translators, Russian literature would be unknown to those of us who don’t speak Russian,” he said.

Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky, famous for their collaborative translations of Tolstoy, Pasternak, Chekhov, Gogol and others flew over from Paris for the fair. They held interactive workshops and talked about “The Enchanted Wanderer,” their new book of stories by Nikolai Leskov, and their plans to create an English version of all Pushkin’s prose.

The 42nd London Book Fair brings together both writers and publishers as well as readers and translators. Source: Tatyana Rubleva

Anna Gunin, who translated German Sadulaev’s lyrical novel “I am a Chechen,” described her job as “part translator, part scout,” strengthening the “cultural bridge” between writers and readers.

“As literary translators, we can be tuned in to what is going on in Russia culturally and help in that process of discovering texts that are something to get excited about,” she said.

Talking about his experiences of introducing western readers to writers like Andrei Platonov and Vasily Grossman, Chandler felt that “if you publish the right books, someone is going to take notice of them at some point,” but he was uneasy with the repeated discussion of sales and marketing, making a plea for “more listening and less pushing.”

Several publishers talked about the difficulties of promoting new writers, but Ola Wallin from the Swedish publishers, Ersatz, said: “We want to surprise people. Our books should be like comets that come from outer space.”

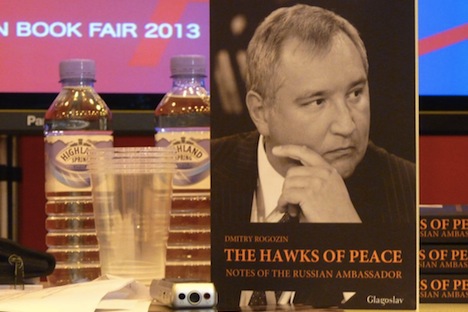

Read Russia’s varied program produced some delightfully eclectic bedfellows. Dmitry Rogozin, Russia’s deputy Prime Minister, was launching the English version of his own memoir, “The Hawks of Peace,” immediately before a session on books for children.

"The Hawks of Peace," a book by Russia's Deputy Prime Minister Dmitry Rogozin, presented at the 42 London Book Fair. Source: Tatyana Rubleva

The crowds of journalists with suits and iphones who materialized to hear Rogozin’s charming blend of nationalism and invective were suddenly replaced by young women in colorful dresses and chunky necklaces talking about kids’ stories.

The architect of the new Yeltsin Center presented his plans for an innovative cultural complex in Yekaterinburg in memory of the eponymous president and next day Rogozin held forth on the catastrophic governance of the Russian 1990s.

What all participants had in common was a love of books and an eagerness to share them with new readers. Rogozin quoted Dostoevsky: “We Russians have two homelands: Our own and Europe.”

A shared interest in great, Russian writers had given him intellectual common ground with politicians and ambassadors the world over, he said. Many of his political pronouncements were controversial, but he insisted: “We need to talk about these things, even if people don’t like it, and this is why I wrote my book.”

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox