Russian campaigns to popularize reading pick up

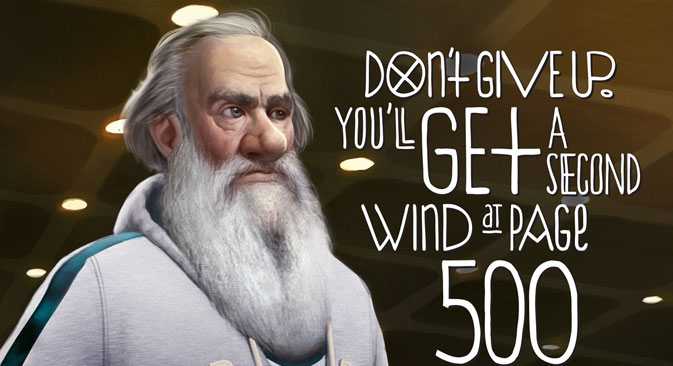

The 'Read' project: The organizers portrayed the powerhouse Russian writers Leo Tolstoy, Anton Chekhov and Alexander Pushkin in athletic uniforms and had them, along with Nikolai Gogol and Fyodor Dostoevsky, rap soulfully. Source: SLAVA

“Ecologists Sound the Alarm: Developers Threatening Ancient Forest,” “Partier Shoots Friend over a Passing Flirtation,” “Wife of High-Ranking Official Kills Self after Argument with Lover,” “Visiting Caretaker Proves to Be Ruthless Dog Hunter”—these and other headlines exploded across the Russian Internet news landscape on September 2, or the Day of Knowledge (when Russian students return to school after summer vacation).

Within the texts of alleged news stories, there were encoded plots of classic Russian literary works: Anton Chekhov’s “The Cherry Orchard,” Alexander Pushkin’s “Eugene Onegin,” Leo Tolstoy’s “Anna Karenina,” Ivan Turgenev’s “Mumu” and many more.

Readers who could not independently identify the works were not left hanging: The headlines led to a specially created portal that connected the news text to the corresponding literary work, which users could then read or download for free.

Click to view the interactive image. Drawing by Natalia Mikhaylenko

“This way, we are demonstrating to Internet users who visit news sites that all plots that can be found in the modern news lines have already appeared in Russian literature somehow or other,” said Yuri Pulya, head of the Periodicals, Book Publishing and Printing Division of the Federal Agency for Press and Mass Communications (Rospechat), which, along with the Russian Book Union and SLAVA advertising agency, is organizing a campaign to encourage reading.

The main goal is to attract attention to Russian classic literature, which, for many Russians, remains only a feature of the school curriculum.

“The result has been an appealing, interesting and, most important, beneficial initiative,” said Pulya. “At the very least, people read these news items on September 2, post them on social networks, and a conversation about literature takes place on several levels.

Also, this sparks creativity: The initiative will make people want to find their own classic literary work and think up a news item based on its plot. And the information noise will make them interested: What is in these works that makes everyone talk about them?”

Anyone could offer their ideas for news headlines based on famous classic masterpieces to the portal of the project and thus take part in the contest, which promised nice prizes.

“Envy prompted sisters to attempt the double murder of a mother and a baby,” or, “Official’s daughter confessed she had dated a lunatic”—readers willingly joined the game, though visitors at some news portals seemed not to realize it was a joke: They revealed their emotions about the fate of an opposition leader’s mother (news based on Maxim Gorky’s novel “Mother” had the headline, “Mother of one of the opposition leaders may be sentenced to a long-term imprisonment”), or discussed the ethical permissibility of experiments on stray dogs.

The movement to popularize literature is a response to a troubling decline in reading, which Russian sociologists bring to light year after year. In summer 2013, the Public Opinion Foundation released data showing that 44 percent of Russian respondents had not read a single book in the course of one year. Just as unsettling is data from the market research company TNS Russia, which states that Russian citizens use media for a total of around eight hours per day, while the time they spend reading a book amounts to just 1.8 percent of that, or about nine minutes per day.

Related:

From no child left behind to every man for himself

It is not surprising that in such a situation the popularization of reading is being given particular attention, including on the governmental level. The National Program for Reading Promotion and Development started in 2006 and includes other memorable initiatives. For example, in last year’s project by Rospechat, “Read,” which targeted teenagers, the organizers portrayed the powerhouse Russian writers Leo Tolstoy, Anton Chekhov and Alexander Pushkin in athletic uniforms and had them, along with Nikolai Gogol and Fyodor Dostoevsky, rap soulfully.

Besides Rospechat, publishers themselves, social organizations and even the city of Moscow are zealously promoting reading. In the last few years, noteworthy initiatives have appeared somewhat regularly.

Some have been more traditional. For example, in “A Word for the Book,” a large 2008 campaign by the publisher ACT, famous Russian writers were pictured on posters describing the importance of reading. There were also projects by the Eksmo publishing house (“Read Books—Be a Character” and “Read Books!”) in which popular figures and musicians, along with Russian soccer players and coaches, discussed the benefits of reading.

Other promotional campaigns are suddenly immersing potential readers in textual medium. Moscow’s subway system boasts “Reading Moscow” and “Poetry in the Metro” trains, whose walls are covered not with advertisements but with excerpts from literary works, authors’ biographies, illustrations of their works and original graphics. The exhibitions are thematic and change periodically.

Source: RBTH

The “Books in the Parks” campaign, which Rospechat launched in 2012, turned five popular Moscow leisure venues into arenas for meeting with writers. In addition, the campaign equipped these venues with “Gogol modules”—kiosks where visitors can purchase books for the lowest price in Moscow. To round out the campaign, grass art portraits of authors were placed in the parks.

Grass art portraits of authors were placed in the parks in the context of the “Books in the Parks” campaign. Source: SLAVA

Next on the agenda is the creation of book clubs all over Russia. They are slated to allow, in particular, for the organization of videoconferences with well-known writers and publishers. The first of these clubs will start in the Russian regions in November of this year.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox