What do Tolstoy, Chekhov and Akhmatova have in common?

Even though Russian literature and poetry in the late 19th century Russian is considered among the world’s finest, there was not a single Russian among the winners before the prize’s award to Ivan Bunin in 1933. Source: AP

From the very first Nobel Prize in 1901, epic quarrels have erupted and rarely subsided over which great author or poet was truly worthy of the Nobel Prize in Literature. In his will, Alfred Nobel founded a distinct award for the author “who shall have produced in the field of literature the most outstanding work in an ideal direction.” But how that has been interpreted over the past century or so has been the subject of articles, research papers and books.

It’s hard to imagine now that in that first year, Leo Tolstoy was not even among the 25 nominees. The first Nobel Prize in Literature was awarded to the little-known French lyric poet and lyricist Sully Prudhomme, sparking indignation in European writing circles. Swedish authors and artists even penned a letter to Tolstoy expressing their objections to the decision of the Nobel Committee.

Later, however, he was nominated four years in a row, but the committee and the secretary of the Swedish Academy, Carl David af Wirsén, could not be moved. Wirsén was generally poorly disposed toward Tolstoy, and maintained that the author “denounced all forms civilization and insisted in replacing them with some primitive form of life, disembodied from every precept of high culture.”

Even though it is now generally agreed that the modern novel was born in Russia, and that Russian literature and poetry in the late 19th century Russian is considered among the world’s finest, there was not a single Russian among the winners before the prize’s award to Ivan Bunin in 1933.

Nominations failed to include Anton Chekhov after he took Russia and Europe by storm. The author of “The Cherry Orchard” and “Uncle Vanya” as well as so many beloved short stories is the most revered Russian playwright in the United States. The Symbolist poet and romantic idealist Alexander Blok was never nominated, and neither was the extraordinary poet Nikolai Gumilev, founder of the Acmeist movement and first husband of Anna Akhmatova.

The author, translator, historian and religious philosopher Dmitry Merezhkovsky was listed on several occasions and is a record holder of sorts: from 1914 there were eight attempts to include him among the candidates, and only in 1937 did the scholars of the committee issue their final rejection, deeming the writer’s “confused” compositions “ to be “mystical religious speculation.”

Another contender was Maxim Gorky, a classic figure of both Russian and Soviet literature. But the Nobel Committee responded unanimously to Gorky’s nomination in 1918 that his “anarchistic and often uniformly grey works do not in any way fit the framework of the Nobel Prize.”

In 1923 the name of the symbolist poet and distinguished translator of European lyricism Konstantin Balmont was unexpectedly included in the list, but he was also rejected and never featured again.

In 1930, Thomas Mann said he was stunned by the epic “The Sun of the Dead,” He proposed that the list should include the author, Ivan Shmelyov, a writer and Orthodox thinker who had long since emigrated to Paris. But the Nobel experts did not give him a very flattering appraisal, commenting that “Shmelyov has the makings of a truly great writer, but did not become one.”

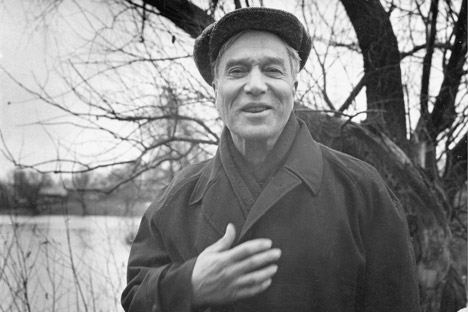

The next prize was awarded in 1958 to Boris Pasternak for his novel “Doctor Zhivago.” But the author was compelled to reject the award by the Soviet authorities.

Boris Pasternak was compelled to reject the Novel Prize by the Soviet authorities. Source: AP

In 1965, the prize went to Mikhail Sholokhov, the only award in the literature category that was sanctioned by the Soviet leadership.

It is impossible to say with any certainty that other Russian writers featured among the nominees, since all information about the Nobel Committee’s work was classified for 50 years. Many and varied Russian authors and poets were worthy of becoming if not laureates then at least contenders for the Nobel Prize – Bulgakov, Platonov, Leonov, Tvardovsky, and later, Belov, Rasputin, Shalamov, Iskander, Aksyonov, Arabov, Petrushevskaya.

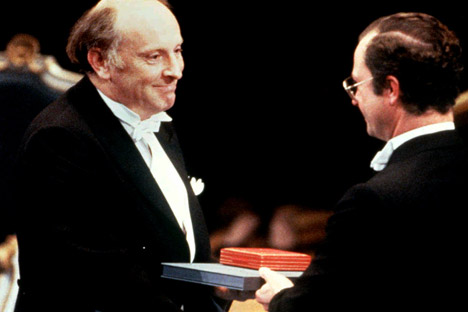

Alexander Solzhenitsyn was awarded with the Nobel Prize in 1970. Source: AP

Rumors abounded in the 1960s that Anna Akhmatova had been nominated for the prize, and in 1972 the laureate writer and dissident Alexander Solzhenitsyn wrote to the Nobel Committee recommending that Vladimir Nabokov be nominated. It was also thought there was a good chance that Andrei Voznesensky, who enjoyed great popularity in the Soviet Union might be nominated. His readings packed huge auditoriums with star-struck audiences. But in 1978 he was awarded the USSR state prize and the Nobel Committee promptly forgot about him.

After the Nobel Prize in Literature went to Joseph Brodsky in 1987 – the year that veteran Soviet heavyweight Chingiz Aitmatov was also said to have been nominated – few people in Europe paid much heed to contemporary Russian writers and poets. Then in 2010 the list unexpectedly featured the names of the poets Bella Akhmadulina and Yevgeny Yevtushenko. And in 2011 Yevtushenko got another run at the prize, along with “Russian intellectual No.1” Viktor Pelevin.

Joseph Brodsky received his Prize in 1987. Source: AP

Perhaps Brodsky would provide the best comment for those masterful and singular Russian writers who never were — or never will be — nominated. “Who enrolled you in the ranks of the Nobel prize winners?” the judge might ask. The answer? “Who enrolled me in the ranks of the human race?” Or even better, Akhmatova: “Today I have so much to do/ I must kill memory once and for all/I must turn my soul to stone/I must learn to live again.”

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox