First book about Viktor Popkov published outside Russia

|

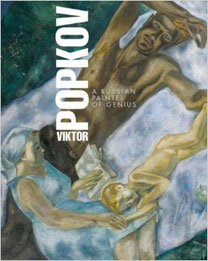

| “Viktor Popkov: Russian Painter of Genius”. Source: Amazon.com |

Viktor Popkov was one of the most celebrated Soviet artists during Krushschev’s Thaw. Perhaps it is for this reason – that he was recognized and not considered an underground artist – that he is less well known, and less appreciated outside Russia than many of his peers.

“Viktor Popkov: Russian Painter of Genius” (Unicorn Press, 2013), is the first book about the artist published outside Russia.

The new book’s author, artist and art historian Pyotr Kozorezenko Jr, told RBTH: “Viktor Popkov … had a unique, artistic personality. In eighteen years of his artistic career he created a vast number of artworks.”

Kozorezenko explained that Popkov is “an enigma, half obscured behind a veil of unquestioningly accepted categories and stereotypes inherited from the now-distant Soviet era.” The book aims to “look behind the textbook image … for the real Popkov, the magnificent, versatile artist who was so paradoxically underestimated and misunderstood…”

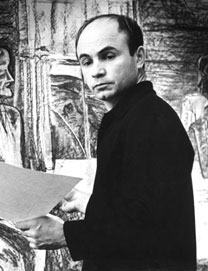

Popkov was born in 1932 and tragically shot dead on a Moscow street in 1974, when he mistook a courier for a cab.

“His paintings are owned by all major museums in Russia and former Soviet republics,” said Kozorezenko. “His works are now very popular and are in high demand with the collectors, fetching over $800 000 per item at Sotheby’s auctions. He is one of the most expensive Soviet artists.”

Kozorezenko’s huge and beautiful tome takes readers chronologically through Popkov’s diverse, stylistic periods, from 1950s Socialist Realism, through the “Severe” or “Austere Style” which he helped create in the 1960s, to his late “Philosophical-Romantic” phase. There is a fascinating progression from the dynamism of his early works to more contemplative figures.

“The Team is Resting” (1965), which became the artistic symbol of the 2012 World Chess Championship in Moscow, uses warm, autumnal colors to show a group of workers, sprawled and sitting, reading and playing chess.

The painting on the book’s cover has similar pensive power: contemporary critics were scathing about “Summer, July” (1969), not appreciating what Kozorezenko calls its “metaphorical dimension”.

Magnificent, versatile and misunderstood

“Spring at the Depot” (1958) seems poised between the glorified heroics of Socialist Realism and the more profound later works. Socialist Realism, the official style of Soviet art from the 1930s to 1950s, was characteristically optimistic; paintings of this period are filled with “the greatness of the Soviet people … painted in light, bright tones…,” Kozorezenko said.

|

| Viktor Popkov. Source: Press Photo |

The Severe Style rejected these “beautifications”, he explains, striving “to depict life as it is, without any pretty illusions. The heroes … are usually engaged in difficult, exhausting labor” and the style involves a “darker, more intense color palette...”

The “Builders of the Bratsk” (1960) is an icon of this style. The workers stand or crouch against an uncompromising, dark background, a group of individuals with their own emotions, but a common goal. The Tretyakov Gallery bought the painting when Popkov was 28 years old.

By 1963, Popkov was already exploring new and original techniques. In “Three Artists,” he creates a scene of thoughtful creativity and deliberately muted power. His own self-portrait in a mirror is framed by the figures he surveys. Kozorezenko describes it as “an intimate, very personal painting…”

Champions of an undervalued era

Popkov is one of Andrey Filatov’s favorite artists and the Filatov Family Art Fund has one of the world’s largest collections of his works.

Andrey Filatov, co-owner of N-Trans, founded the Filatov Fund last year, with the aim of collecting Soviet works of art from around the world bringing them to a global audience.

Filatov told RBTH: “The Filatov Family Art Fund is the first fund that focuses on bringing together paintings, drawings and sculptures from the Socialist Realism period that left Russia mainly after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.”

The paintings in Filatov’s growing collection range from ideological icons like Vladimir Serov’s “Lenin Proclaims Soviet Power” to atmospheric still lives and landscapes. He plans, initially, to add a dozen new works each year.

It is not all red flags and happy workers, insists Filatov: “The art from this period extends far beyond its well-known use as a Soviet propaganda device and includes strong elements of art-deco, impressionism and even the synthetic style of modern art.”

The book is the first in a series published by the fund. There are plans for a book about the Russian-American painter, Nikolai Fechin, next year and for exhibitions of both Popkov and Fechin. The fund sponsored a display of Fechin’s work in Seattle, and added his “Taos Girl with Sunflowers” to the collection earlier this year.

Filatov is championing an artistic era that he feels is “undervalued compared to other Russian or US and European peers both in terms of appreciation and financially.”

The Filatov collection includes several well-known images, like a plaster model by the monumentalist sculptor, Vera Mukhina, for her stainless steel “Worker and Kolkhoz Farmer.”

“The aim of the fund is to make the works of these Russian artists available to the public,” Filatov told RBTH.

Through books and exhibitions, he hopes to nurture “a better understanding of the significance and skill of artists from this important period in Russian history.”

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox