Rebel with a cause: The political messages in Pushkin’s fairy tales

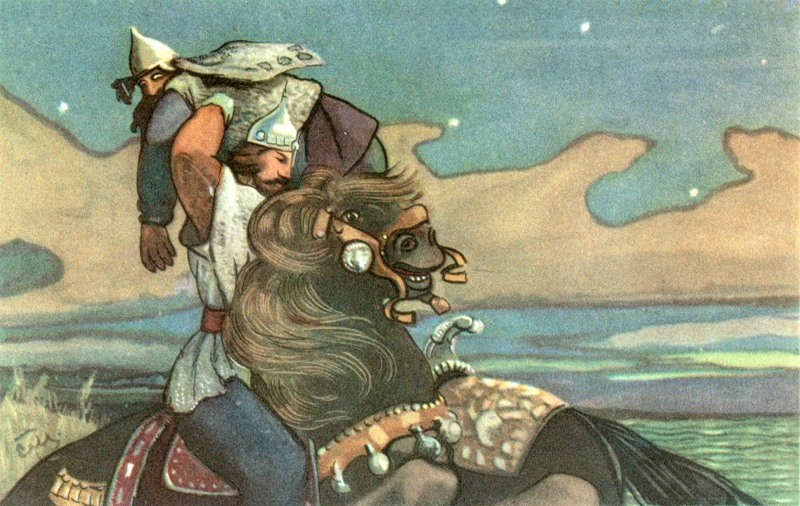

Ivan Bilibin. Illustration for "The Tale of The Fisherman and The Fish," 1908. Source: Fine Art/Vostock-Photo

As well as being recognized as a great writer during his lifetime, Alexander Pushkin was also a successful civil servant. He graduated from the Imperial Lyceum, an elite educational institution established by Tsar Alexander I, and went on to work in the Russian Foreign Office. However, despite working at the heart of the establishment, Pushkin had a social conscience and began attacking the government in his writing. He joined the clandestine Union of Welfare and wrote a series of political poems that were widely circulated in manuscript.

Brilliance in exile

In 1820, Pushkin was summoned by the governor general of St. Petersburg, Count Miloradovich, to explain his epigrams and revolutionary poems that were circulating at the time. Initially, the authorities were planning to exile the poet to Siberia, but thanks to the intervention of his influential friends, he was “only” banished from St. Petersburg and sent into exile in the Caucasus, Moldova and Crimea. This period turned out to be one of Pushkin's most productive times, during which he wrote many romantic poems and his brilliant work Eugene Onegin.

Pushkin's controversial poems resurfaced in 1825 when they were linked to the failed Decembrist Revolt to overthrow Tsar Nicholas I, but the tsar allowed the poet to return from exile the following year, believing that he had abandoned his revolutionary sentiments. In fact, Pushkin had simply decided to be more discreet. By this point he was already renowned as a great poet and was aware that the tsar himself was closely scrutinizing his works. However, if we read the series of verse fairy tales he wrote in the 1830s in the political context of their time, we find that there is often more to them than meets the eye.

A reformed character?

One Pushkin's first fairy tales, “The Tale of Tsar Saltan,” published in 1831, tells the story of a tsar who chooses the youngest of three sisters to be his wife. However, her elder sisters become jealous of her status and when she gives birth, they arrange to have her sealed up in a barrel and thrown into the sea along with her baby son, Prince Gvidon.

The pair wash up on a remote island, and the prince, who grew while in the barrel, goes hunting and ends up saving an enchanted swan from a predatory bird. The swan creates a city, where the prince rules successfully. Eventually the swan turns into a princess and marries Prince Gvidon, who is finally reunited with his father, the tsar.

This story of separation and reunification can be seen as a thinly veiled allegory of Pushkin's own situation and was perhaps designed to convince Tsar Nicholas I that the writer truly was reformed.

A veneer of conformism

Whether or not Nicholas did see the parallels between Pushkin and Prince Gvidon, he allowed the writer to continue publishing, and even commissioned literary works from him. In 1833, Pushkin wrote “The Tale of the Fisherman and the Fish,” which is about a fisherman who catches a golden fish that promises to fulfill any wish in exchange for its freedom. The old fisherman and his wife have been poor their whole lives, and the sudden opportunity to get rich sparks an intense greed in the wife. First she asks for a palace, then to become a noblewoman, then to become the provincial ruler, and finally the Tsarina. Eventually the couple loses everything when the woman wants to become the Ruler of the Sea.

Robert Chandler, a renowned Russian literary translator has argued that the fisherman’s wife is a caricature of Empress Catherine the Great. The empress deposed her husband Peter III, effectively usurping his power in the way that the fisherman’s wife does. She also fought two wars with the Ottoman Empire to gain dominion over the Black Sea – fruitless campaigns that wasted a great deal of money and lives.

Pushkin as a political tool

Other fairy tales reveal different and more politically compelling stories. Pushkin was an atheist, which was unusual for the time and the circles he moved in. “The Tale of the Priest and of His Workman Balda” is about a lazy priest who tries to exploit a cheap worker. Russia was highly religious at that time, and the attack on an Orthodox Church priest would have been seen as blasphemous. The fairy tale, written in 1830, was published posthumously in 1840, and the character of the priest was replaced with a merchant to avoid a backlash from the powerful Church. However, the priest was reinstated in Soviet publications of Pushkin’s fairy tales – the government of the new Russia had its own political ax to grind.

This fairy tale is also about exploitation, which was very prevalent in a society where serfdom was still legal. At the end, the priest is criticized for “rushing off after cheapness,” and this was also something that the communists exploited a century later. The first Bolsheviks looked back over works by Russian 19th-century writers to find acceptable messages they could use in creating the new socialist culture, and Pushkin’s work proved brilliant in this respect. His views on serfdom, the Orthodox Church and the oppressive tsarist state fitted neatly into the communist outlook, so the writer was promoted and revered from the first years of the Soviet Union – even more so than in the 19th century.

Pushkin’s last fairy tale in verse, “The Golden Cockerel,” was written in 1834, three years before his tragic death in a duel. The story,which was based on “Legend of the Arabian Astrologer” from Washington Irving’s “The Tales of the Alhambra,”was not political in any way. However, when Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov adapted it into an opera in 1908, he turned it into a satire on the waning Romanov dynasty and the Russo-Japanese war, which was one of the most humiliating events in Russian history. “The Golden Cockerel” was Rimsky-Korsakov’s last opera, initially rejected by the censors and only staged after the composer’s death.

Find our more in our multimedia section:

A very Western Pushkin

The highlights of Alexander Pushkin's creative life

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox