How Dr. Dolittle became Dr. Aybolit

Many masterpieces of western children’s literature came to Russia

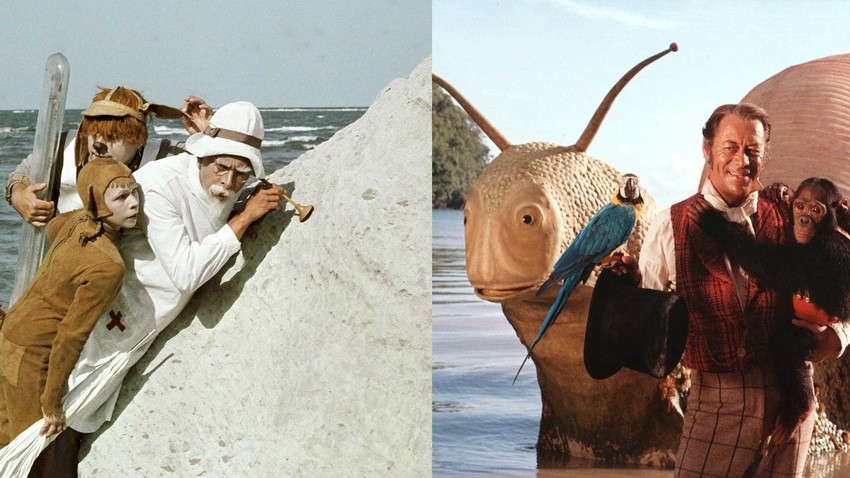

Dr. Dolittle and his colleague Dr. Aybolit

Russian Dr. Aybolit vs. American Dr. Dolittle

RIA Novosti & AFPIt all started with Korney Chukovsky and his Dr. Aybolit, which means "Dr. Ow-It-Hurts." Dr. Aybolit is closely related to Hugh Lofting’s Dr. Dolittle, but Chukovsky claimed that he came up with the idea of writing a story about a kind doctor completely independently. In a short article called “How I Wrote the Story Doctor Aybolit,” Chukovsky wrote, “I thought of it back before the October Revolution because I met the real doctor Aybolit, who lived in Vilnius.

His name was Dr. Shabad. He was the kindest person I ever met in my life. He treated the children of the poor for free. […] Children didn’t just come to him by themselves; they also brought their sick pets. So I thought how wonderful it would be to write a story about such a kind doctor.”

However, Lofting got his idea down on paper first, and Chukovsky adapted the British author’s story. “When I was reworking his cute story for Russian children, I christened the protagonist Dr. Aybolit and added dozens of

The adaptation was released in Russian in 1924, and it was only a year before Chukovsky’s first poem about Dr. Aybolit appeared. This marked the start of a whole cycle of confrontation between the kind doctor and the villain Barmaley. The storyline remotely resembles Lofting’s story in some places, but Chukovsky rendered it in his own original way, and Soviet children were totally won over by the work.

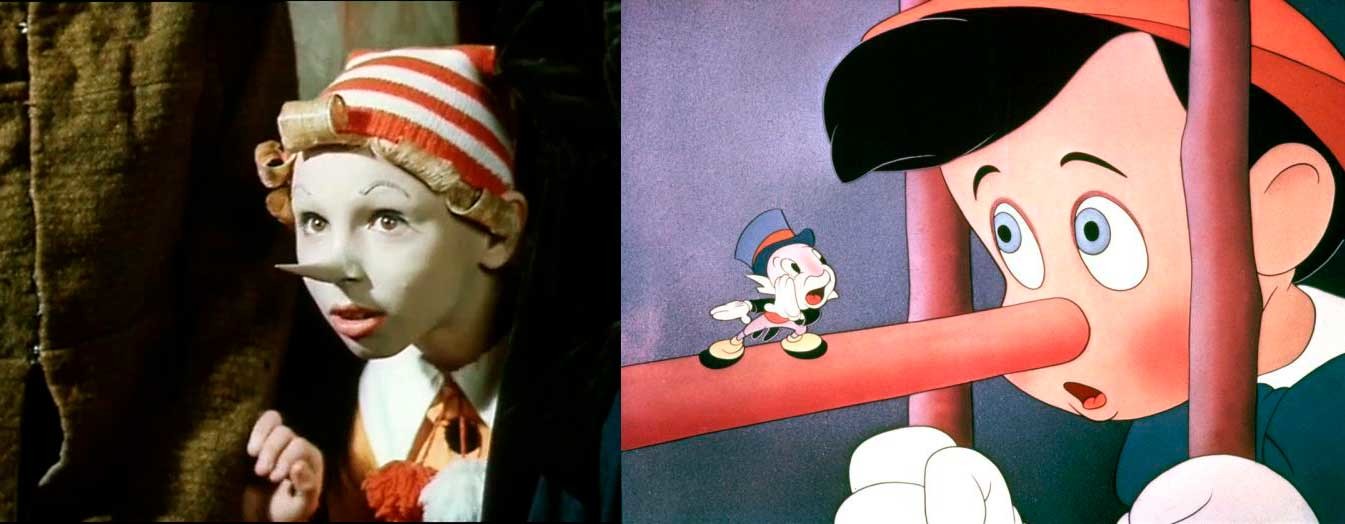

Pinocchio and his brother Buratino

Buratino VS Pinnochio

Kinopoisk.ruThe next story in this chronological survey is The Golden

It all started with an honest attempt at translation. However, the writer Aleksei Tolstoy – a remote relative of Leo Tolstoy who embraced the revolution and was nicknamed the Red Count – allowed the heroes of The Adventures of Pinocchio to flourish under his pen. In 1935, Tolstoy wrote to Maxim Gorky: “I am working on Pinocchio. At

Tolstoy didn’t just change Pinocchio’s name to Buratino; his character didn’t long to be a real boy – he remained a cheerful puppet instead, and his nose didn’t get longer like his Italian counterpart.

Mangiafuoco, the benevolent puppet master in the original story, is transformed into the ruthless tyrant Karabas Barabas in Tolstoy’s version. Karabas Barabas’ puppets run away from him and in the end, after a series of adventures, find their own theater where they can play by their own rules. The golden key, the story’s main symbol, unlocks the door to this special place.

Soviet children fell in love with The Golden Key, which featured less philosophy, more action, and a happier ending than its western counterpart. Adults also appreciated the Russian version’s allusions, palindromes, and other word games, as well as its recognizable prototypes.

Little Soviet girls dreamed of dressing as the puppet Malvina for New Year parties – in Collodi’s version, she is a fairy with blue hair. Buratino himself became a brand and lent his name to a popular mineral water. This

Old Man Hottabych – the cheerful genie

Soviet Old Man Hottabych VS Genie

Kinopoisk.ruTurn an ancient genie into a Soviet citizen? Why not? Lazar Lagin, the former deputy editor-in-chief of the USSR’s leading satirical magazine, Krokodil, decided to take on the challenge. “I tried to imagine what would happen if a genie were rescued from captivity by an ordinary Soviet boy like the millions in our happy socialist country,” the author said.

Lagin’s genie adapts to day-to-day life in the Soviet

The propagandist edge to Lagin’s story stopped it from transitioning into a treasure of Russian children’s literature from a well-loved piece of Soviet literature, but in its time it brought plenty of laughs to children all over the country.

In the preface, Lagin refers his readers to the stories One Thousand and One Nights and Aladdin and the Enchanted Lamp, forgetting to mention Antsey’s novel The Brass Bottle, which has clear overlaps with Lagin’s work, both in terms of the plot as a whole and specific scenes and details. Old Man Hottabych was first published in 1938 in Pionerskaya Pravda and was later released as a separate edition.

The Wizard of the Emerald City

The Wizard of the Emerald City VS. The Wizard of Oz

Kinopoisk.ruAccording to the official version, the teacher Alexander Volkov picked up a copy of Baum’s story to improve his English. He was charmed by the book and started retelling it to his children, before turning his hand to translating it. The translation evolved into a retelling, which Volkov decided to send to Samuil Marshak himself, the editor-in-chief of the country’s main children’s publishing house.

When the Oscar-winning film The Wizard of Oz came out in the United States in 1939, the Russian version of the book was published in the USSR for the first time. The title page of the first edition contains the modest line “Based the story by L. F. Baum,” and the book is identical to the original in many ways. However, Dorothy’s name is Ellie in the Russian version, her dog Totoshka can talk, and there are new scenes that do not appear in the original. Subsequent versions were less and less similar to the original and were published without reference to the source.

The Wizard of the Emerald City met with such astounding success that Volkov began to receive stacks of requests from readers to continue the series. He held out for 25 years and then wrote another five works which, with the exception of rare details, did not overlap at all with Baum’s stories.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox