Glas publishing house is suspending its activity

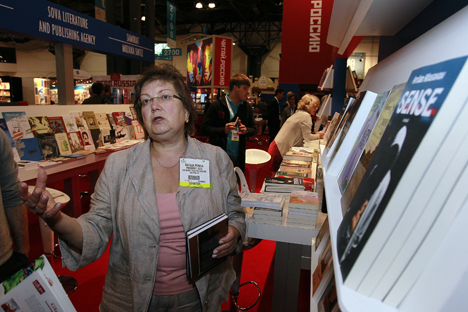

Natasha Perova at BookExpo America. Source: Valery Levitin / RIA Novosti

Treasure

Perova says she first discovered contemporary Russian literature and “fell in love with it” when she was editing Soviet Literature magazine in the late 1980s. “I felt I ought to share this new-found treasure with people from other countries who only knew our 19th-century classics,” she told RBTH. Glas publishing house, its name derived from the old Russian word for “voice,” was born in 1991. “I was reading avidly,” Perova recalls. “There was a huge accumulation of unpublished books known to readers only through unofficial samizdat copies.”

“Later, when literary prizes reappeared in Russia … I followed their selections,” she says. “But I mainly trusted my own intuition.” It worked: prize-winning writers Victor Pelevin, Vladimir Sorokin and Lyudmila Ulitskaya are just three of the many authors Perova championed before larger publishing houses snapped them up. “I only regret that for lack of funds I could not publish all the books I admired,” she says. “Many brilliant names have been overlooked by foreign publishers.”

“Initially I wanted to embrace the entire literary scene and published only anthologies,” she says. “There was too much good material: new works, formerly banned books, and rediscovered classics from the 1920s and 30s.” Glas has published 75 titles over 24 years, but, since half of them are anthologies, these volumes contain 170 different authors “representing various trends and types” of Russian literature.

Translators

“The Portable Platonov” anthologized new translations by Robert Chandler and others. Joanne Turnbull, co-editor of Glas, won the Rossica prize for her translation of Sigizmund Krzhizhanovksy, another forgotten Soviet storyteller making a posthumous comeback. Perova modestly says that she owes the translators everything: “They came to me themselves and showed great support.”

Michael Glenny, famous for his translation of “The Master and Margarita,” was an early supporter of Glas. The first volume of Glas is dedicated to Glenny, whose “irrepressible energy and enthusiasm sustained our determination at the start.”

Translator Arch Tait, who helped edit Glas in the 1990s, praised Perova’s altruistic dedication, her keen eye for literary talent, and tireless “filtering” of thousands of manuscripts. “Natasha has published hundreds of people for the first time in English,” he told RBTH.

There were difficult days ahead. “I thought the world would gasp with admiration,” says Perova, but “both publishers and the public were slow to appreciate contemporary Russian literature.” The first print run of 125,000 was scaled down dramatically, but there was always an appreciative audience. Perova says that the “invariably supportive and complimentary” readers' letters were what kept her going in the tough early days.

Russia in the raw

The cause of Russian literature in translation is not helped, Perova feels, by the recent rise of émigré Russian writers who “paint a more digestible picture of Russia.” Foreign publishers are scared, she says, of “Russia in the raw, with its miseries and struggles” and readers are spoiled by “smooth-moving, light fiction.”

Perova also sees a clear connection between the declining market and geopolitics. “Our American distributors told me this summer that due to the worsening attitude towards Russia they can no longer sell our books successfully,” she says. However, the distributor in the UK, where sales are also down, will continue selling back titles as long as they have them.

As a Russian publisher of works in English, Perova’s project is not eligible for grants at home or abroad. “I can’t apply for help anywhere,” she explains. “Due to falling sales and rising costs … it is no longer possible to publish translated literature without external support, which I have never had.” Despite this, Perova plans to continue promoting new and overlooked authors: “New talents keep springing up. I’ve always been on the lookout for them.”

Academics, critics, writers and readers have paid tribute to Glas over the years. George Steiner called the series “disturbingly indispensable”; Tibor Fischer wrote a glowing review of the 2006 anthology “War and Peace,” which first showcased Arkady Babchenko’s memoirs of the Chechen War. “I must say that we have collected enough praise along the way to convince me that we have not worked in vain,” Perova says. “I have never regretted a single publication,” she adds. “Each is interesting and important in its own way.”

Discover Russian literature with RBTH

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox