Andrei Tarkovsky: Biography wrestles with the filmmaker’s remarkable life

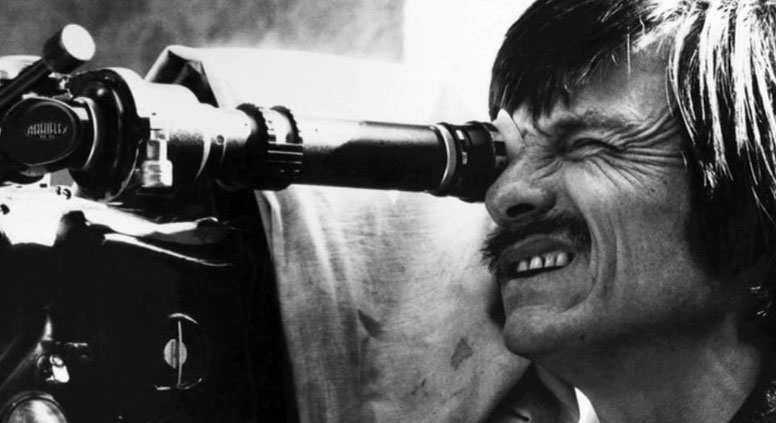

Christopher Culver translated the book, that recreated a like of Russia's great film director. Source: Kinopoisk.ru

The metaphor underlying Lyudmila Boyadzhieva’s fictionalized biography is the image of revered Russian filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky as Christ. With his messianic approach to creativity – “for me making films is a moral activity,” she quotes him saying – and his ideological persecution by the Soviet authorities, Tarkovsky is ripe for hagiography.

Boyadzhieva does not flinch from portraying his human failings, too. Tarkovsky may have been a genius and cinematic pioneer, but clearly he could also be a very annoying man. He was misogynistic – “a woman does not have her own inner world” – stubborn, insecure, naïve, irritable, intolerant and “provocatively direct.” His observational skills, Boyadzhieva remarks dryly, lay more in “a refined perception of the smallest manifestations of the outside world, than in knowing how to relate to people.”

“Tarkovsky’s seven-and-a-half films are a drop of something different in the ocean of commercial and simply bad cinema …” Boyadzhieva writes at the start. But she herself finds it harder to escape generic clichés. When Tarkovsky’s father, the poet Arseny, woos his future wife Maria in a park, he “took her in his strong arms.” She later tells him: “You’re my hero … Life will be wonderful!” and they quote Lermontov together.

Christopher Culver’s energetic translation grapples valiantly with the stilted dialogues, giving young Tarkovsky some amusing, slightly anachronistic teenage slang: “cool kicks,” “whoa, man.” At film school, Tarkovsky first announces his plans for a new kind of provocatively realist cinematography: “Let them crucify me.” His friend Andron responds, “A life on the cross!” Symbolically, this scene takes place on Sparrow Hills, Moscow’s best-known viewpoint. Boyadzhieva’s lumpy prose is a steaming casserole of cultural references.

|

| 'Andrei Tarkovsky: Life on the Cross,' by Lyudmila Boyadzhieva, 2014. Source: Glagoslav |

“A Life on the Cross” devotes a chapter to each of Tarkovsky’s films, analyzing their slow catalogue of self-referential allusions, recurring motifs and portentous images. Boyadzhieva continues to recreate the director’s life at the time: the scandals surrounding the bleak, miraculous “Andrei Rublev”; the homesickness behind “Nostalghia”; or the desolate, otherworldly “Sacrifice,” shot in Sweden. Her imagery is variously biblical or bestial: Tarkovsky is “baited,” trapped or driven “like a horse.”

There are moments of macabre beauty, from the hand of an actress, “blood-stained with cranberry juice,” to the Parisian white roses on Tarkovsky’s wintry coffin. He died aged 54 in 1986. Boyadzhieva highlights his unique cultural role and symbolic, global legacy. “He embodies the image of the Russian artist for the West,” she writes, “and for Russia the image of the rejected messiah.”

Read more book review in our special section Literature

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox