Lev Shestov: Russia’s answer to Kierkegaard and Nietzsche

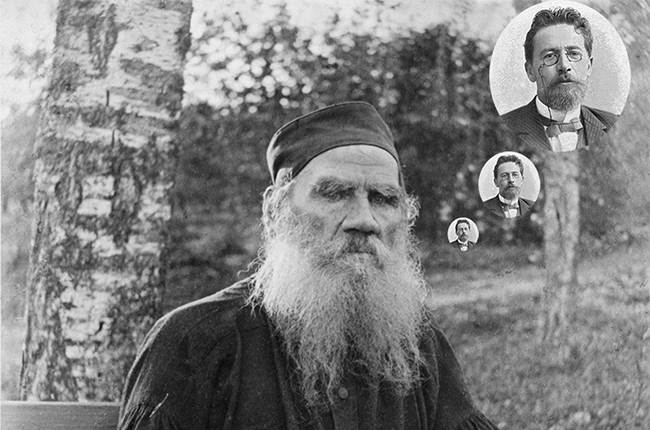

Lev Shestov 1902

Press Photo Lev Shestov, 1902. Source: Press photo

Lev Shestov, 1902. Source: Press photo

Although today in our age of consumerism, dominated by oil prices and key rates, we have little time to reflect upon our being, about 100 years ago a whole philosophical movement was gaining ground in Europe that focused precisely on man's existence. One of its early exponents was Russian-Jewish thinker Lev Shestov.

Nothing on earth is impossible

Born Lev Isaakovich Schwarzmann into a big prominent family in Kiev, in what was then the Russian Empire, Shestov studied mathematics at the Moscow State University and then law back in Kiev.

Unhappy working in his father's textile business, he joined a circle of rebellious fin-de-siècle writers and philosophers that included Dmitry Merezhkovsky, Vasily Rozanov and Nikolai Berdyaev, who all flirted with Socialism/Marxism in their youth only to become champions of the Christian worldview in their mature age. Berdyaev, in fact, also came to be associated with existentialism, although he concentrated mostly on spiritual and creative activity as the purpose of human existence.

Shestov gained recognition with his two early books, The Good in the Teaching of Tolstoy and Nietzsche (1899) and The Philosophy of Tragedy, Dostoevsky and Nietzsche (1903). But it was with the controversial Apotheosis of Groundlessness (1905) that he brilliantly tapped into the zeitgeist of the overturning world and laid out the central tenets of the budding philosophy.

In this aphoristic, unsystematic, sarcastic work Shestov tears up just about every tradition, ideology and idea that prevents man from realizing his maximum potential. "Nothing on earth is impossible," says the author, explaining that man should believe only in himself, in his immediate being, that he is absolutely free to construct his identity as he so wishes.

A pair of eyes so as to see beyond the natural world

Disgusted with the Bolshevik regime, in 1920 Shestov left Russia with his wife and children and settled in Paris. In the City of Light he contributed to philosophical journals and lectured at the Sorbonne, where he befriended phenomenologist Edmund Husserl, with whom he would remain in contact for the rest of his life.

In the book In Job's Balances (1929) Shestov employs Judeo-Christian themes to illustrate the limits of science and objective reason in obtaining genuine knowledge. Instead, he posits that only individual experience can bring man closer to the ultimate truths, which lie beyond the evident and outside necessity.

He speaks of the Angel of Death all covered with eyes visiting Dostoevsky on the scaffold and instead of taking his soul (Dostoevsky was pardoned just as the firing squad was taking aim) the angel gave him a pair of eyes so that the writer could see beyond the natural world, "that things do not exist ‘necessarily’ but ‘freely,’ that they are and at the same time are not."

There is no such thing as fate or the divine will

Although Shestov believed in God, he maintained that there is no such thing as fate or the divine will. Man's aim in life is to fight this illusion, to continuously assert his subjective ever-changing self. It is this struggle to overcome certainty and inevitability that defines existentialism, as expounded in Kierkegaard and the Existential Philosophy (1934).

In 1938, the year in which he died, Shestov published Athens and Jerusalem, in which he summarizes his stance on religion, reason and freedom, putting the final nail in the coffin of rationality.

"But why attribute to God, the God whom neither time nor space limits, the same respect and love for order? If God loves men, what need has He to subordinate men to His divine will and to deprive them of their own will, the most precious of the things He has bestowed upon them?"

Shestov's influence was vast. Among writers and philosophers who would later cite him were D.H. Lawrence, Georges Bataille, Albert Camus and Isaiah Berlin. Unfortunately, today he is little known. His indulging in religious iconography and allusions to morality wearied 20th-century existentialist readers, who had already reached a psychological plateau beyond good and evil.

Nevertheless, Shestov remains an important building block in the tower of existentialism, a philosophy that, like every other, has long been devoured by the greatest consumer of all – time.

Subscribe and get RBTH best stories every Wednesday

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox