Eastern pioneers: The first Russian explorers of Malaysia

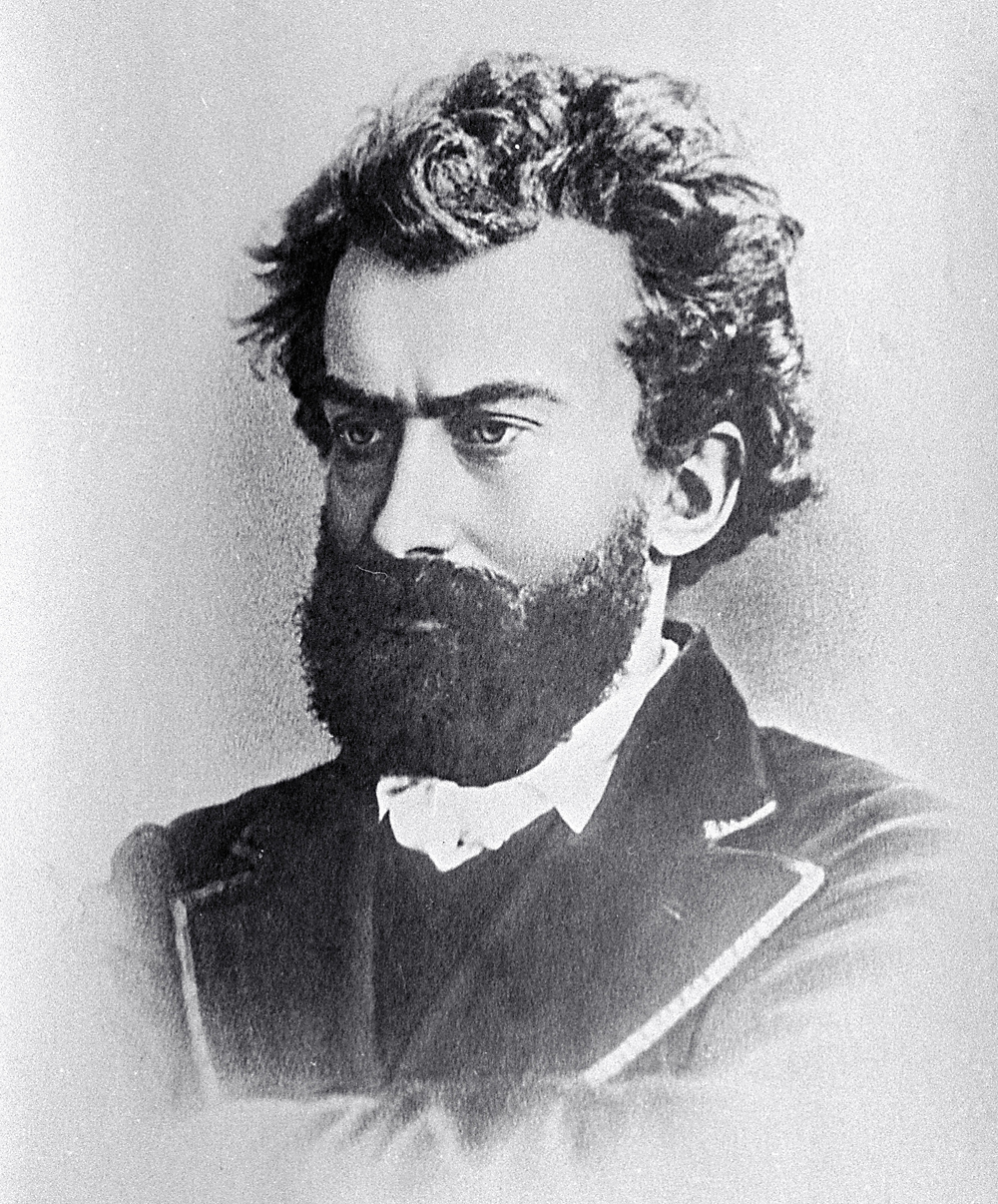

Naval officer Alexei Butakov, 1865.

G. Denier/ liveinternetKnowledge of Malaysia and Malays originally came to Russia from Western sources until Russian travelers managed to visit the Malay Peninsula.

One of the first Russian travelers was naval officer Alexei Butakov, who met Malays for the first time in 1842 on Penang Island. He sought to understand the character of the Malays and their attitude to the outside world.

Comparing them with other Oriental peoples that he had met, Butakov was full of praise for the Malays. “Malays have more noble qualities,” he said. “They are loyal, true to their word.” Butakov was also fond of the Malay language, which reminded him of Italian.

When Butakov managed to talk to Malays, he tried to tell them about his native land. Russia was hardly known among the inhabitants of Penang, who had never seen snow in their lives. A mullah on the island was completely surprised by Butakov’s tales about Russia.

Ancient manuscript and literary influence

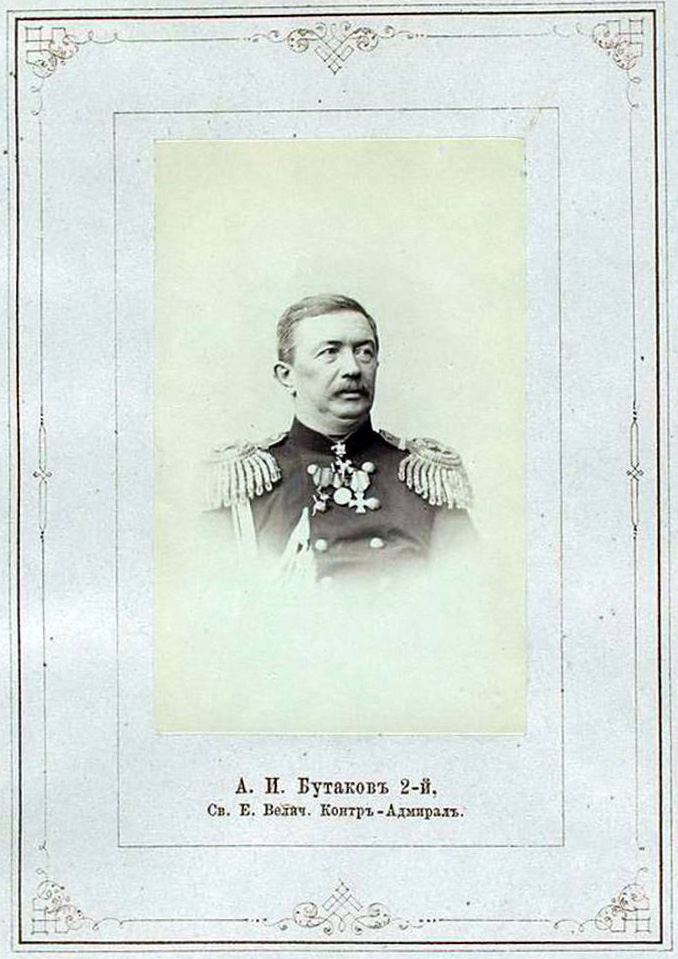

Famous Russian navigator Ivan Krusenstern visited Malaya during one of his Pacific voyages and in 1798 brought back a famous work of Malay literature, a copy of the manuscript of Sulalatus Salatin, or Malay Annals.

The manuscript was written at the height of the Malacca Sultanate in 1400-1511. Back in Russia, Krusenstern handed it over to academician Christian Fren, who in turn presented the manuscript to the Asian Museum (now, the Institute of Oriental Manuscripts in St. Petersburg).

The manuscript, which carries Fren’s autograph, says that Krusenstern had received permission from ‘officials’ to make a copy of the text of this ‘history’, which was highly valued in Malaya. In Russian this manuscript was first published only in 2008 thanks to the efforts of St. Petersburg-based orientalist and ethnographer Elena Revunenkova.

Surprisingly, Malay literature had an influence on Russian authors. At the turn of the 20th century, poets like Valery Bryusov, Adelina Adalis, Alexander Zhovtis, and Grigory Permyakov all created works imitating Malay forms of poetry, including the traditional form of pantun.

In Bryusov’s ‘Malay Songs’ written in 1909, one can easily spot numerous references to islands of the Malay Archipelago such as the scent of champak flowers that the wind is giddy with, figs, bananas, pandanus, coconuts, a paddy field, tigers in the jungle, white waves on the beach.

British dominion

Another prominent Russian source of information about Malaysia at the time was an academic work by geographer and traveler Mikhail Venyukov called ‘Essay on the contemporary state of British dominions in Asia,’ published in 1875.

Portrait of the Russian explorer Ivan Kruzenshtern. Source: monarch.hermitage.ru

Portrait of the Russian explorer Ivan Kruzenshtern. Source: monarch.hermitage.ru

Venyukov analyzed British rule in the colonies and methods of colonial exploitation. The scientist left a striking description of the colonizers’ attitude towards the local population. He called it “an attitude of haughty conquerors from a superior race towards the defeated masses of people, whom they not only rob but also gradually and systematically destroy.”

That attitude remained unchanged for a long time. Russian writer Alexander Fedorov, who was traveling around the world in 1903, left a horrified entry in his journal. “In front of our very eyes, one of the enlightened Europeans threw his cigarette on the bare back of his rickshaw-puller.”

Anthropological studies by Miklouho-Maclay

A special role in studying Malaya belongs to Russian scientist Nicholas Miklouho-Maclay, who visited the Malay Peninsula twice in 1874-1875. He was fortunate that Sultan Abu Bakar of Johor appreciated the importance of the scientist’s research and rendered him every possible assistance. He supplied the Russian traveler with letters of recommendation and helped him with organizing the expedition.

During the Russian’s stay in Johor, Abu Bakar provided him with a palace. However, Miklouho-Maclay did not remain there long. He was eager to study as many tribes and ethnic groups as possible.

Miklouho-Maclay traveled on foot, rode on elephants, crossed rivers on rafts and Malay boats known as perahu. The rainy season brought unexpected difficulties. Rivers burst their banks and travelers had to walk through the forest, waist-deep in water. Yet, when he reached villages, Miklouho-Maclay always received a friendly welcome from the locals. He managed to gather anthropological and ethnographic data on many Malaysian tribes.

Trade and World War I

In 1890, Russia opened its consulate in Singapore, which dealt with organizational and other issues arising over the stopover of Russian ships. In 1900, there were over 40 such stopovers. The ships refueled en route from the Baltic Sea to the Pacific Ocean. The consulate also made it possible to receive more objective information about the state of affairs in Malaya.

Interestingly, in 1903 Sultan Ibrahim Shah of Johor expressed an interest in visiting Russia during one of his trips to Europe (he was probably searching for a counterbalance to Britain). The Russian Foreign Ministry agreed but there are no subsequent reports about the Sultan’s visit to Russia. It must have been cancelled because of the Russian revolution.

During the First World War, the Russian fleet was engaged in fighting in that part of the world. The Western Road cemetery in Georgetown on Penang has a grave of Russian sailors from the cruiser Pearl, which was sunk by the Germans in October 1914.Russian consul general Artemy Vyvodtsev more than once raised the issue of the need to expand trade with Malaya, pointing out that Russia could import copra, tin, silk-cotton, capped pineapple, black pepper from there.

Even in the early 20th century, Vyvodtsev linked trade relations with the Malay Archipelago to the development of Siberia and the Russian Far East. He felt that products from factories to be built in Asian Russia could be exported to Southeast Asia and could easily compete with freight from Europe.

During the First World War, the Russian fleet was engaged in fighting in that part of the world. The Western Road cemetery in Georgetown on Penang has a grave of Russian sailors from the cruiser Pearl, which was sunk by the Germans in October 1914. An obelisk was erected on the grave in 1975.

Gradually and largely thanks to indefatigable Russian explorers, Russia learnt more and more about the far-away country of Malaysia, which ultimately enabled the two countries to establish and maintain strong and friendly relations.

Read more: In the Last Emperor’s words: Life as a prisoner in the USSR

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox