Coping with Afghan and Chechen syndrome

Psychologists describe it as post-traumatic stress disorder—when the human mind struggles to cope with the aftermath of war. Others simply call it Afghan or Chechen syndrome.

Clinically, it refers to a series of psycho-pathological experiences whereby the mind attempts to erase the memory of past stress-inducing events, keeping the victim in a state of anxiety for months and sometimes years.

This photo-story tells about the wartime lives of Russian soldiers and their subsequent adaptation to civilian life.

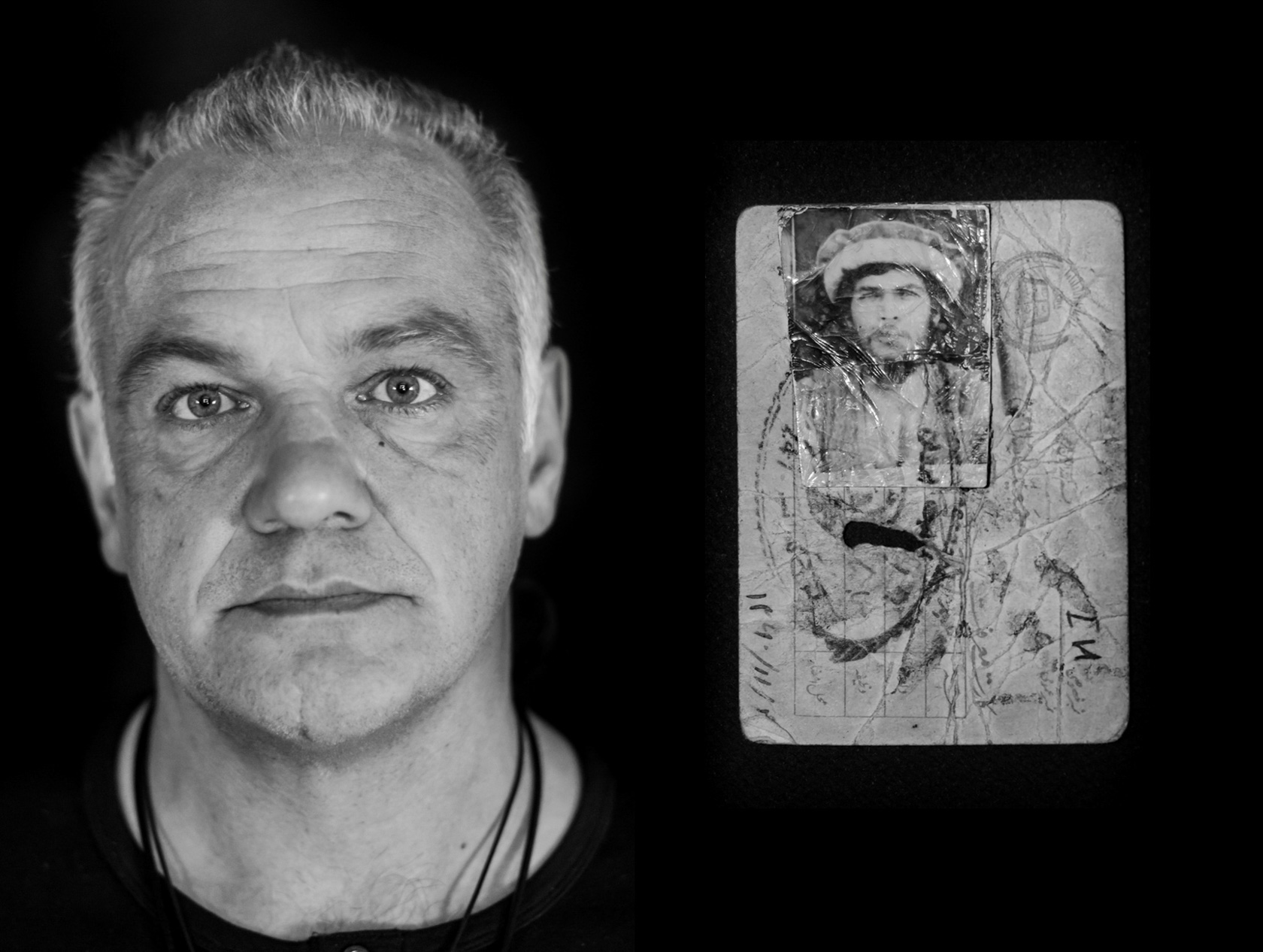

Vladimir Kravchenko

1985-1987

Afghanistan (Ghazni Province)

Artem ProtsyukWe were in a tank and rode over a landmine. The turret was blown about six meters up into the air. The gunner was lying at the bottom of the vehicle, and I was caught between the hatches under what was left of the turret. Miraculously everyone survived.

Artem ProtsyukWe were in a tank and rode over a landmine. The turret was blown about six meters up into the air. The gunner was lying at the bottom of the vehicle, and I was caught between the hatches under what was left of the turret. Miraculously everyone survived.

Back home, I hit the vodka. I was on the bottle for ten years.

Without my new family and job I wouldn’t have got through it. They pulled me out of the hole.

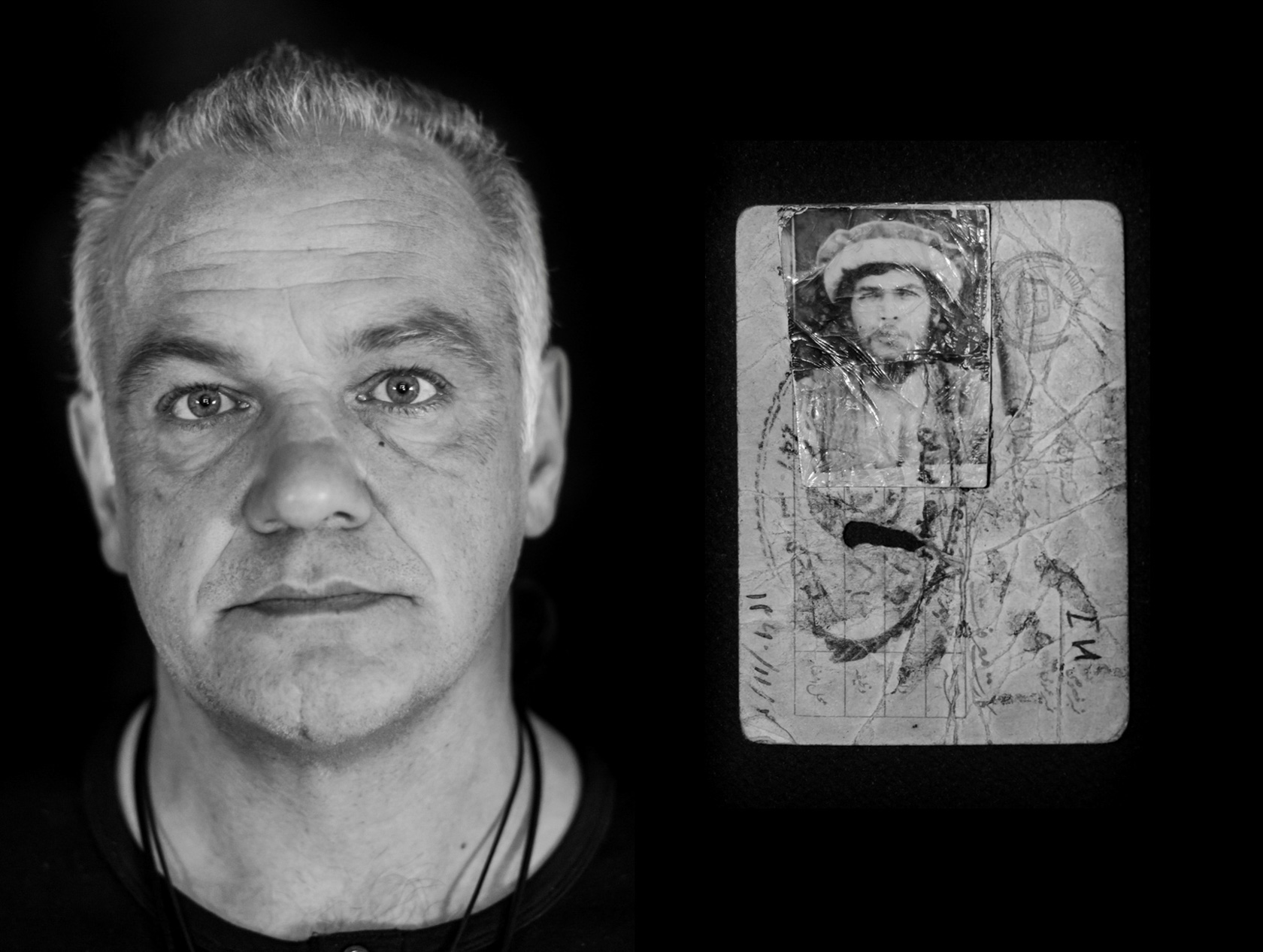

Dmitry Dagas

1983-1985

Afghanistan (Bagram, Panjshir)

Artem ProtsyukAs a war trophy, I ended up with the passport of a “ghost” who was trying to shoot me [Soviet soldiers referred to the mujahedin as dukhi (“ghosts”) because they often couldn’t see them]. It’s a good job I was quicker that day.

Artem ProtsyukAs a war trophy, I ended up with the passport of a “ghost” who was trying to shoot me [Soviet soldiers referred to the mujahedin as dukhi (“ghosts”) because they often couldn’t see them]. It’s a good job I was quicker that day.

After the war I spent five months in a hospital bed with concussion and an amputated leg. My illness caused me to stammer and my eyes started twitching. I had these phantom pains where my leg used to be, which became real when I got a badly fitting artificial limb. I was looking for sympathy from others, but soon realized you can’t expect anything from those around you.

I didn’t know what to do with my life and started to drink. A friend pulled me off the booze by taking me on a camping trip—three weeks of fresh air and female company worked wonders. After that, I decided to sign up for art school and start a new life. I think that friends and art rescued the human being inside me.

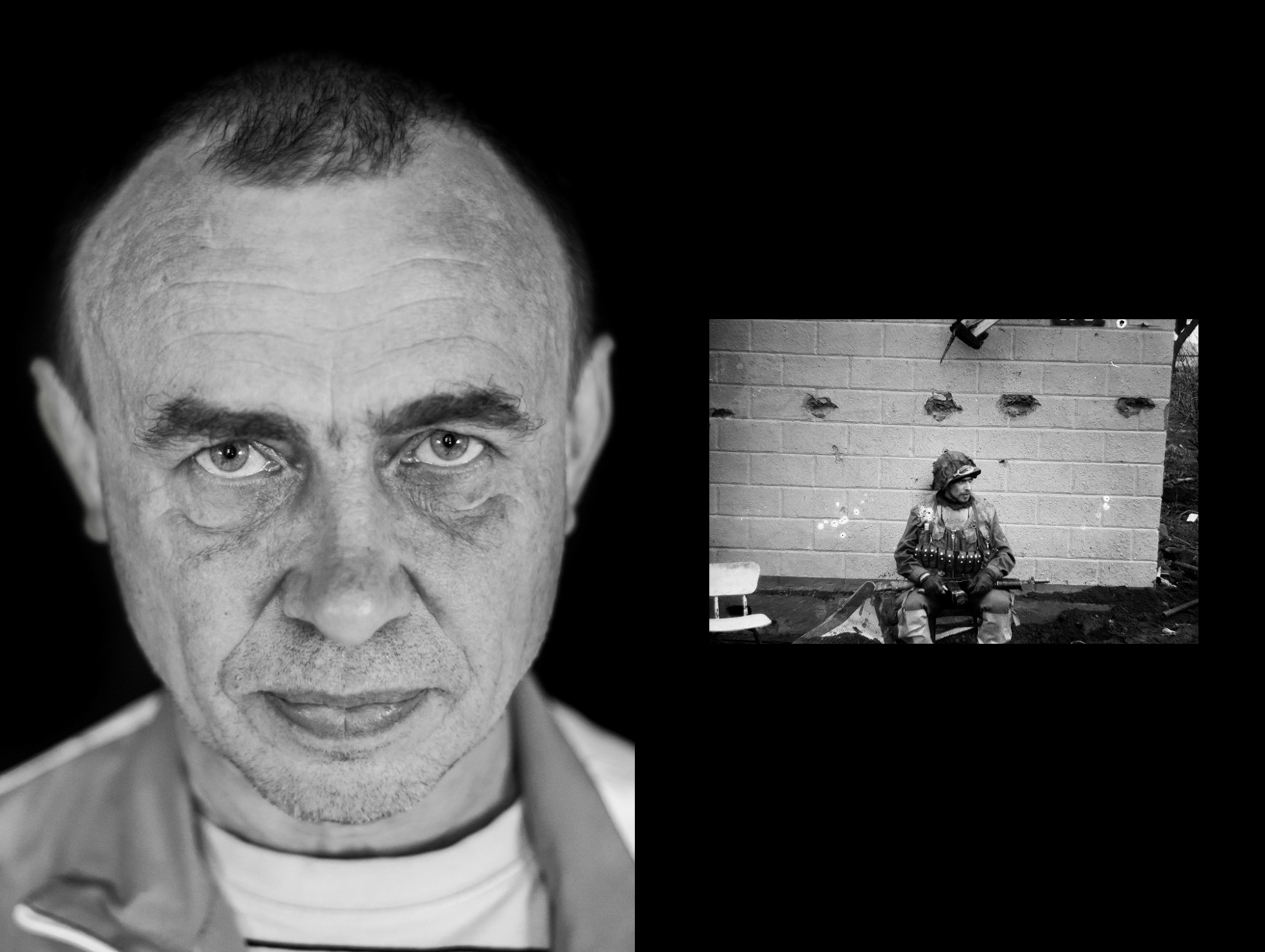

Oleg Ryabikov

1995

Chechnya (Grozny)

Artem ProtsyukWhile sweeping militants in Grozny in winter 1995, we came under friendly fire. I had to flee from my own side, and the operation failed. Fortunately, we didn’t lose anyone that day.

Artem ProtsyukWhile sweeping militants in Grozny in winter 1995, we came under friendly fire. I had to flee from my own side, and the operation failed. Fortunately, we didn’t lose anyone that day.

Back in civvies, it turned out that no one gave a damn. Life went on as usual. People didn't care about the war in Chechnya and all the horrors that were going on there. The only ones who weren't indifferent were our families.

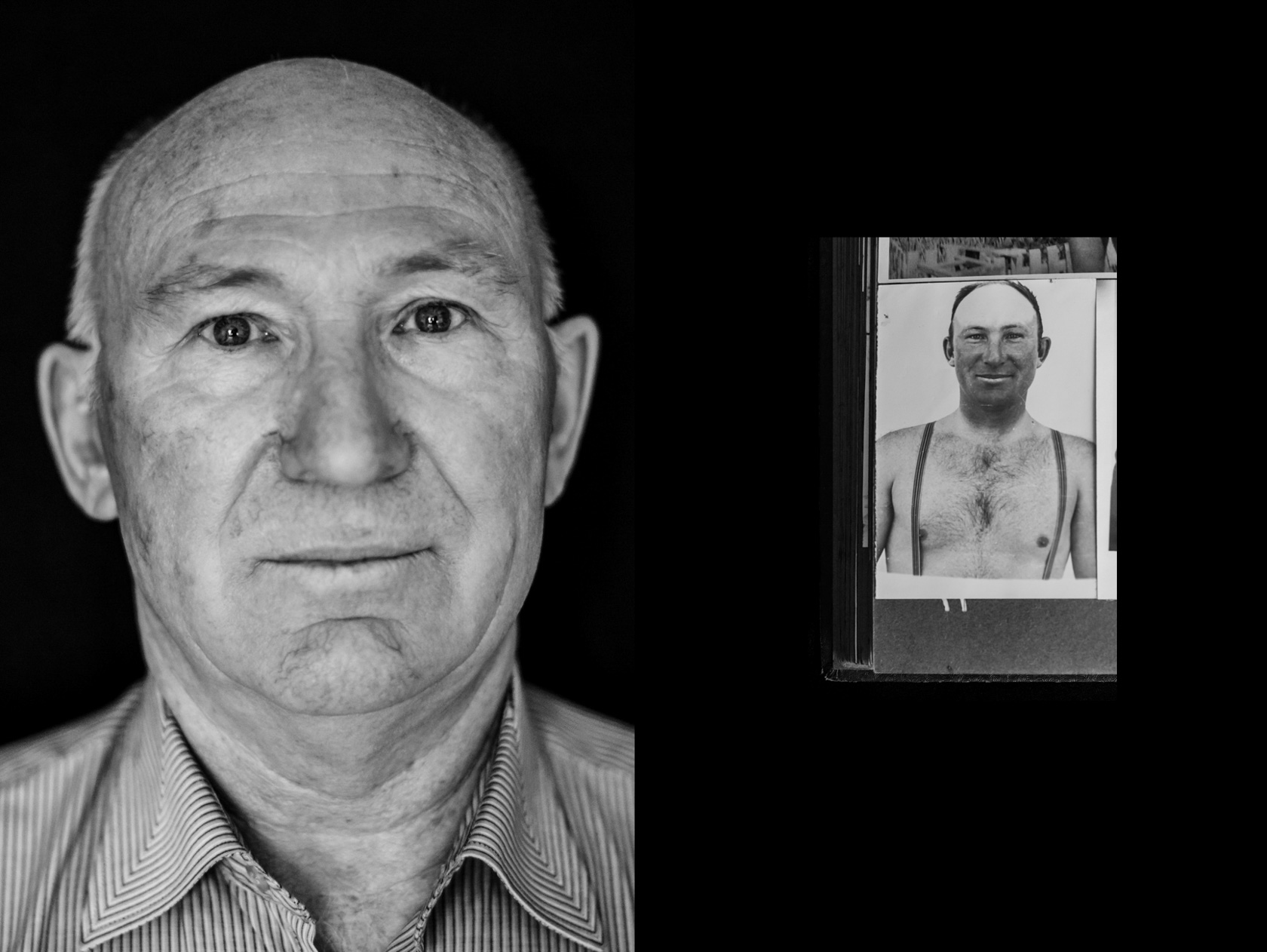

Mikhail Alimov

1981-1983

Afghanistan (Kandahar, Shindand)

Artem ProtsyukSomehow our convoy of 42 trucks came under fire. Shoot-outs look good only in the movies. When it happens for real, you're getting hit from all sides. You don’t even know who or where it’s coming from. Me and my driver Nikolai stuck a machine gun through the window and started shooting in all directions.

Artem ProtsyukSomehow our convoy of 42 trucks came under fire. Shoot-outs look good only in the movies. When it happens for real, you're getting hit from all sides. You don’t even know who or where it’s coming from. Me and my driver Nikolai stuck a machine gun through the window and started shooting in all directions.

Suddenly he gave a shout and I realized he'd been shot in the throat. I asked if he could still drive. “Sure” was the answer. I put pressure on the wound, while Nikolai grabbed the wheel. We somehow managed to get back to friendly territory. After this incident, HQ issued an order for convoys to keep moving at all times in such situations.

Adapting to civilian life was tough. The war didn't let go. The images kept circling around my head.

Although I didn’t want to go back to Afghanistan, I had no regrets about the time I spent there. That’s nothing to do with patriotism or inflated self-esteem. I just did what I had to. Thank God, I got through it alive.

Vladimir Popov

1999-2010

Chechnya

Artem ProtsyukEvery soldier carried two “spare” cartridges: one for himself and another for a friend—to avoid suffering or capture if the time came.

Artem ProtsyukEvery soldier carried two “spare” cartridges: one for himself and another for a friend—to avoid suffering or capture if the time came.

That was one reason why we felt wild back home as civilians. Everything was overwhelming and unfamiliar. You try to get a job, but war’s the only thing you know. It really weighs on you and is hard to deal with. That period of trying to fit in breaks some people. They start drinking or taking drugs, or become criminals.

The first six months at home I was on edge. Every tiny sound made me jump and glance around for the enemy. It was hard to fathom that people were just out walking and cars were driving around. I was constantly catching the sight lines, looking for the best place to position the machine-gun crew, where to put the sniper.

I was helped back to normal life not by psychologists, but fellow veterans. It's easier to talk to a guy who’s been there himself.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox