{***Arctic payoff is worth the cost***}

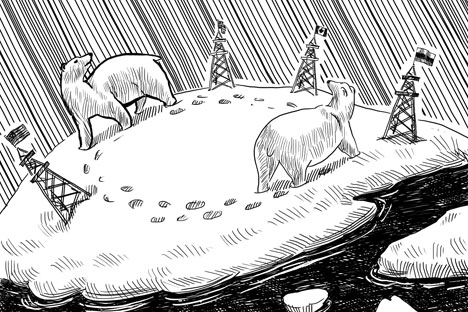

Drawing by Konstantin Maler. Click to enlarge

Read Alexander Pilyasov's opinion on the next page

When we consider the expected outcomes of the development of natural resources in the Arctic, it is necessary to first of all understand who will benefit, who will bear the costs, who will make the decisions about development and, finally, if the loser will find a way to compensate the winner.

Where does Russia fall in this analysis? In developing Arctic resources, Russia and Russian companies must ask all these questions.

One important, perhaps primary, objective for Russia of developing Arctic reserves is to ensure the country’s energy security. Russia’s proven oil and gas reserves are great and its resources are even greater.

Yet, they will inevitably be depleted, and the task of developing difficult and remote oil and gas fields, including those in the Arctic, is becoming more and more relevant for Russia. For example, in 2010, gas production on the Yamal Peninsula, which is located beyond the Arctic Circle, and in sparsely populated territories of East Siberia and the Far East made up only 5 percent of Russia’s total gas production; by 2035, their share may grow to as much as 43 percent.

Estimates of oil and gas resources in the Arctic vary, but even as a rough approximation, it can be said that the oil and gas reserves in the Russian sector of the Arctic are comparable to all of Russia’s proven oil and gas reserves.

Having said that, oil and gas fields in the Arctic are yet to be found. Still, this huge treasure trove may become an important element of energy security, all the more so since Russia for the foreseeable future will retain its high dependence on oil and gas production. In this analysis, Russia is clearly the winner, but also the party that will bear the costs.

So, for Russia, is searching for oil and gas in the Arctic and learning how to carry out exploration and production in the northern seas or on permafrost worth the effort and expense? Given the presence of huge undiscovered resources there and the tangible depletion of the existing oil and gas fields, the answer to the question is yes.

While the Arctic also has relevance for global energy security, Russia has a particular need to develop these resources. According to International Energy Agency estimates, only 2 percent of the world’s oil and 6 percent of the world’s gas resources are located in the Arctic.

While this is still substantial, the Arctic could hardly be called a critical factor for global energy security. Unconventional oil and gas, such as the kind that can be obtained through fracking, offer far more opportunities for other energy producing countries. And even though Russia, too, has shale oil resources that can be explored — the Bazhenov Formation may have oil and gas reserves as great as those in the Arctic — developing the lands above the Arctic Circle is still important. The future competitive ability of the Russian oil and gas sector depends on it.

Russian polar expert says Arctic too important to ignore

Long-term competitive advantage is based not so much on low costs as on knowledge and skills. The firms that learn how to carry out efficient and safe operations in the Arctic will score numerous points in the race for leadership in the international energy markets. Developing this technology is of interest to Russian companies and their foreign partners alike.

However, from the point of view of the public and the state, the situation is not that straightforward. Certainly oil and gas projects in the Russian North can contribute to economic growth, generating taxes, creating jobs and producing orders for the domestic industry.

But opponents of these ventures argue that investing in these projects also leads to an ever-deeper dependence on oil and gas production and processing, taking the country farther away from the task of diversifying its economy. State subsidies and other incentives given for Arctic exploration could be used with just as much benefit in other sectors, the argument goes.

Perhaps Russia should not be pouring more money into the oil and gas sector while the prospects for the country’s economy as a whole are not that bright. But while the cost-benefit analysis is worse in the Arctic when compared with the development of conventional hydrocarbons, at the current oil and gas prices, Arctic projects will still be quite profitable.

According to International Energy Agency estimates, the cost of production in the Arctic may be $40–100 per barrel of oil and $150–460 per 1,000 cubic meters of gas. Oil is currently trading at $100 per barrel and, in the long term, is likely to go up in price. At the moment, Russia is selling gas in Europe at about $400 per 1,000 cubic meters and the price is unlikely to fall.

Despite the apparent profitability of Arctic projects, companies will not be able to cope without additional incentives. Last year, the Analytical Center for the Government of the Russian Federation carried out an assessment of means of state support for Russian offshore oil and gas projects.

It turned out that it was only an extensive package of incentives and preferential terms that allowed a majority of those projects to break even. The reason for this was not only that the projects were costly, but also that the tax burden on this sector in Russia is quite heavy and not amortized very effectively.

Now the authorities have concluded that the sum total of the positive effects of developing Arctic oil and gas reserves is such that they should be given a chance.

For society as a whole, the question of whether the development of the Arctic is the right move does not have a clear “yes” or “no” answer. We simply do not yet know enough about the Arctic, and the region itself is quite diverse.

The solution to this problem is to do more research in the Arctic zone, develop and test the necessary technologies and make a decision on developing each specific oil or gas field taking into account a range of economic, environmental and social costs, alternative options and the long-term priorities of Russian and global energy security.

Alexander Kurdin is the head of the directorate for strategic energy research at the Analytical Center of the Government of the Russian Federation.

{***Arctic development more than cost-benefit analysis***}

Weighing the costs of developing the Arctic against the potential benefits is a crucial question for Russia, but it is no less crucial a question for other Arctic states. Take Norway, for example, which has for several decades been engaged in offshore oil and gas production, investing considerable funds in the development of its Arctic territories, and has been a global leader in Arctic innovations.

Then there is Canada, which has a very modest Arctic population compared to Russia, but has for the past decade been building up its research and intellectual presence in the region, primarily through setting up new polar research centers at its universities.

Given these developments, Russia cannot even question the expediency of its efforts to return to the Arctic after the crisis decade of the 1990s. These efforts are perfectly in line with global trends.

In the 1990s, the Russian Arctic fell out of favor domestically. Severe cuts affected the funding of the icebreaker fleet; support for the indigenous peoples of the North dried up; and the Arctic polar research programs, including the North Pole drifting station project, were canceled altogether. Now Russia is only partially restoring the scale of its Soviet-era presence in the Arctic region.

For Russia, there is no alternative except to develop the Arctic. Today, the status of an Arctic nation is not granted automatically, but requires painstaking work and a daily commitment to discover new knowledge about the natural and social processes under way in the Arctic zone.

Russia is ready to make this commitment. After all, without the Arctic, what would Russia be in terms of its area and gross domestic product? Its international standing would be much diminished.

Russia needs to develop the Arctic if only to build on the development already established during the Soviet era. The country already has substantial investments in development there, and not only in terms of natural resources extraction. Several major cities in the region could use infrastructure support. However, the question of how to ensure the country’s presence in the Arctic economically and efficiently is a crucial one.

How much is Russia really spending on developing the Arctic?

One project that has been cited as a huge expenditure is the program to upgrade the Soviet-era fleet of icebreakers. So far this program is being carried out on a very modest scale and a very unambitious timetable.

This program is moving slowly despite the fact that Russia’s geological knowledge and degree of exploration of its Arctic continental shelf is very much behind the relevant U.S. and North European achievements, yet efforts to bridge this gap have so far been clearly inadequate.

Additionally, Russia has not implemented any major infrastructure projects in the Arctic over the past decade. The infrastructure that has been developed is mostly on the individual scale, such as the development of the Prirazlomnoye oil field by Russian oil major Lukoil.

The most visible and sizable resources over the past several years have been spent on collecting data to substantiate Russia’s claim to several million square kilometers of continental shelf near the Mendeleev Ridge. Russia has spent hundreds of millions of dollars on this work. This is an absolutely unprecedented price of “staking a claim.”

It cost 19th-century gold prospectors much less to stake a claim to gold fields in California, the Yukon Territory and Alaska. These costs, however, were necessary expenditures. In 1997, Russia signed the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea as part of its drive to further integrate into the international community.

The convention grants signatories exclusive economic rights to sea and continental shelf 200 miles from the sea baseline. However, the convention also allows signatories to make claims to an extended continental shelf within 10 years from signing the convention.

In December 2001, Russia filed such a claim. In the years since, the country has spent substantial amounts on Arctic exploration to support its position.

But aside from this exploration, why are the plans for Russia’s large-scale return to the Arctic being implemented so slowly?

Here it is necessary to make one clear distinction between Arctic development projects being carried out by the government and those being carried out by companies, both private and state-owned. Firms like Lukoil, Rosneft, Gazpromneft and others are focused on implementing a specific project, be it on land or offshore. These projects, as a rule, are governed by the principles of the market economy and envisage a generation of profit in the medium term.

But the broad approach of the state goes beyond a simple balance sheet of costs and benefits, and it goes beyond a specific project. This approach is concerned with the development of the entire Russian segment of the Arctic and focuses on infrastructure development for present and future generations of Russians.

This approach is concerned with sustainable development for centuries to come. Naturally this approach is broader than pure economics. It involves ideas of sovereignty and Russian statehood, and the role the Arctic plays in these ideas.

It is important to realize that these are two different approaches that should not be compared or confused, but should coexist. The best kind of state Arctic policy will ensure harmony between them, so that as a result of public-private partnership, the interests of all players are integrated for the sake of a sustainable development of the Russian Arctic in the interests of people living there and all Russians.

Alexander Pilyasov is the director of the North and Arctic Economy Center under the Council for the Study of Productive Forces and a professor of economics and management.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox