A ‘new’ National Holiday serves to unite 11 time zones

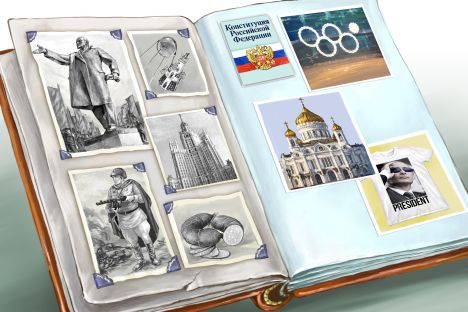

Drawing by Dormidont Viskarev

On Nov. 4, Russian citizens will celebrate National Unity Day. This is a relatively new Russian holiday, which came into our lives in 2005.

It was brought to life for a number of very obvious reasons. The creation of a new – Russian, not Soviet – nation required new symbols. We had to find an event that was in the vicinity of Nov. 7 [the anniversary of the 1917 October Revolution, the official national day of the Soviet Union from 1918 to 1991 – Russia Beyond] to create a holiday that could replace the Soviet tradition.

However, National Unity Day is not simply a young holiday. The historical roots of this particular date reach back to the beginning of the 17th century and the end of the Time of Troubles (a period of national and dynastic chaos from 1598 to 1613), when Polish troops were expelled from Russia and the new Tsar Mikhail Romanov was crowned. Bulkily named the Day of Moscow’s Liberation from Polish Invaders, it was an important and stately holiday but, in my opinion, deprived of any necessary emotional connection to modern Russia.

The newly founded Nov. 4 holiday has yet to earn its place in the hearts of all Russians. I’m sure that there is no holiday in Russia today that can be compared in its unifying power with May 9 – U.S.S.R.’s Victory Day in the Great Patriotic War and World War II.

This war is still embedded in the hearts of all Russian citizens, their fates and human connections. The memory of the war and the pride of victory for their parents and grandparents undeniably unite the new Russian and Soviet histories. And on National Unity Day, these similarities are things we dwell on.

At the same time, Russians are significantly freer in their judgments than the Soviet people. We got all the constitutional rights which they could not dream of in the Soviet Union – the right to freedom of movement, freedom of speech and the right to property. Today’s Russia is a capitalist country, where the government is trying to maintain its social responsibility to its citizens, which is very difficult in the current economic situation.

The role of religion in society has changed. Freedom of conscience, as stated in the Russian constitution, has led to the increased development of our country’s traditional religions – Orthodox Christianity, Islam, Judaism and Buddhism. But unity can also grow out of this multi-confessionality, even if Russia is a very secular state.

Today, patriotism is quite often, and wrongly, in my opinion, regarded as a kind of national ideology. Such an understanding, ironically, is a threat to our national unity.

Patriotism, in a pure sense, is a normal human feeling – like loving your parents – and is usually not related to the political beliefs of a person. However, it is important for society and individuals to distinguish between patriotism and nationalism.

One should not forget that patriotism is inherent in all people, and should be a unifying emotion even in people of different ethnic backgrounds: in Russians as well as in Tatars, Bashkirs or Chechens [Russia’s second, fourth and sixth largest ethnicities, respectively – Russia Beyond].

The monument to Minin and Pozharsky, who played a crucial role in the nation's history, saving the country from Polish conquest

Getty ImagesCertainly, every people has its own language, its intangible heritage – customs, traditions, rules of conduct, art and culture. Not everything matches, even if the peoples belong to the same linguistic group or share a common religion.

Russia is a country where multiculturalism is accompanied with some general civil rules of conduct. I will make no secret of the fact that it is extremely difficult at times to maintain the balance of interests of different peoples living side by side. But this should be the goal of every forward-thinking country.

When celebrating National Unity Day, a decade after its recreation in its current form, Russians will draw upon these themes of multi-culturalism, multi-confessionalism and what it means to be from a country with two intertwined histories: Soviet and Russian.

Certainly our poets and filmmakers and ballet dancers and musicians serve as a common well of culture for Russians to drink from: Whether it’s 19th-century classical music or the defining movies of the ‘90s, we don’t need to look too far to find similarities.

As Russians learn to cherish this new November holiday, whatever their ethnicity or political leaning, they can dwell on the unifying glory of Victory Day in the recent past or on the historical Day of Moscow’s Liberation from Polish Invaders.

Mikhail Shvydkoi was the Minister of Culture of the Russian Federation (2000-2004).

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox