Why Russia hopes for realism from the next U.S. president

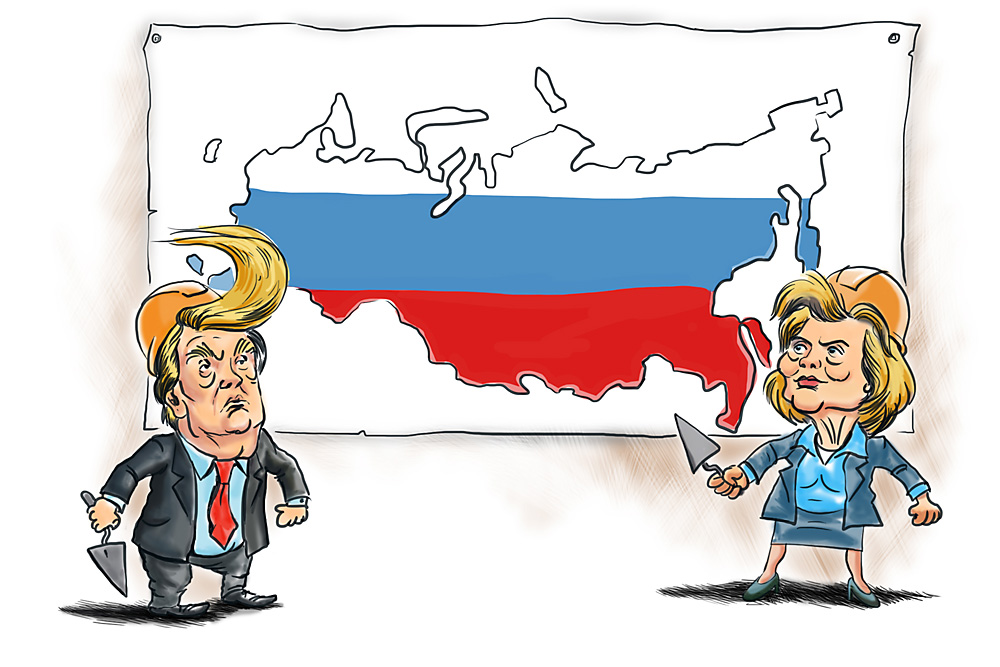

Drawing by Konstantin Maler

It seems that the New York primaries have put everything in the American presidential race in its place. Only a miracle can prevent the former first lady from becoming the Democratic candidate. The Republicans have much less clarity, but it is very likely that the decision concerning Hillary Clinton's challenger will be made at the party convention and not as a result of the primaries.

However, failing to elect the politician who received the most votes in the preliminary stage (Trump) is a risky act. It would only emphasize that which many Americans, judging by the primaries, are against: the dominance of the establishment, which is completely indifferent to most people's point of view. But there is also a rational argument: The unpalatable Trump is almost guaranteed to lose against Clinton, while a more conventional Republican would have a chance of winning.

Perception of Russia is a blend of alarmism and skepticism

Russians usually say that it makes no difference for Russia who gets into the White House. This opinion is not groundless. Firstly, despite all the power he or she wields, the U.S. president is not an autocrat and cannot drastically change the mood of the public and its attitude to Russia. It is Congress that forms the political atmosphere in America, and there the perception of Russia is very particular and rather negative.

A heavily critical approach to Russia also prevails in America's intellectual community. Ivan Safranchuk, an international affairs expert from the Moscow State Institute of International Relations, who has recently studied the spectrum of expert evaluations in the U.S., sees that the perception of Russia is determined by an informal coalition of what he describes as "alarmists" and "skeptics," who are united by their aversion to Russia's contemporary political model.

Republicans and neo-conservatives make up the alarmist category: These people consider Russia a threat, one that needs to be countered and severely restrained wherever possible. The skeptics meanwhile are made up of liberal interventionists who think that Russia is an untenable model and the best tactic is moderate restraint coupled with the expectation that Russia will exhaust its own potential.

Realists do not play a role

Safranchuk notes that experts and politicians who usually fall into the realistic school of thought (such as Henry Kissinger) do not play a role today, especially with respect to Russia. Other vivid examples of this thinking (such as John Mearsheimer's 2014 article in Foreign Affairs magazine blaming the West for the Ukrainian crisis) are being attacked from all sides. And it is not about Russia as much as it about the fact that if America's actions were to be evaluated from the perspective of political realism, doubts could be cast on the basic postulate about the success of and lack of alternative to America's post-Cold War course.

At a certain point there was even a curious discussion among American commentators regarding whether or not President Barack Obama is a realist. The conclusion was that he is not. He had created expectations but did not understand that America's prestige must be supported not with words but also with precise acts of force.

For now the American discussion is being held within a narrow circle of reflection on the lack of alternative to America's leadership in the world and the U.S.'s general exceptionality. These mantras are being repeated by all presidential candidates, yet no one seems to have a coherent foreign policy, with the basic position being to criticize Obama and/or express their convictions that they know what to do.

As strange as it may seem, Trump does have a consistent line of thought. His scandalous statements concerning America's allies such as "It's time to stop feeding Europe" (in the sense of security guarantees) or about Japan and South Korea having to think of their own defense against nuclear North Korea are aimed at reducing America's burden and responsibility. And most Americans favor this position.

However, in the blunt manner in which Trump presents the issue it will obviously never be realized. Besides, whoever becomes president will have to be more restrained and will have to take into consideration the international situation.

This may force the White House to return to a less ideological agenda, either in the next four years or in those following, during which a very serious battle for America's orientation in the future will be waged. It is then that political realism may be rehabilitated in America, something that Moscow would obviously welcome.

First published in Russian in Gazeta.ru

The opinion of the author may not necessarily reflect the position of RBTH or its staff.

Subscribe to get the hand picked best stories every week

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox