Pictured L-R: Vladimir Putin, Sergei Ivanov, Sergei Shoigu during the Victory Day celebrations in 2016.

RIA Novosti / Sergei GuneyevRussia Direct: Why and when did you decide to write such a book?

Mikhail Zygar: In fact, I was writing this book approximately for seven years. That is, I was collecting information for this book for seven years: I had to meet with numerous newsmakers and conduct off-the-record interviews with them.

During all these years, I was working as a political journalist for different media outlets. I started this book when I worked for [business daily] Kommersant. Then I became deputy editor-in-chief of Russian Newsweek and, afterwards, I moved to the Dozhd TV channel as editor-in-chief.

Mikhail Zygar. Source: Facebook Mikhail Zygar. Source: Facebook |

Dealing with Russian political journalism means that newsmakers can be relatively outspoken only during off-the-record interviews. It is impossible to have honest and sincere conversations on the record. That’s why, in order to be a political journalist in Russia and fulfill the commitments of an editor, I had to conduct off-the-record interviews to learn all the ins and outs of Russian politics and understand what’s important and what’s not, what’s really going on under the surface of Russia’s political agenda.

So, at the earliest stage, in 2007, I came to an idea that I had to come up with a book that would include these off-the-record interviews. At that moment, it seemed to me that it would be easy and fast enough to fulfill this task: I planned to sum up the results of Putin’s two presidential tenures.

However, afterwards, [with the third presidential tenure of Putin and the start of the Ukraine crisis] it became clear that the book would not end that way and it was too early to come up with conclusions. Only in 2014 did I understand that a certain political epoch had ended and it was high time to release the book to remind readers about the events that had taken place during Putin’s three presidential terms and what the origin of this political epoch was. So, I had to finish the book.

RD: You mentioned that most interviews were off-the-record. Is this the reason why your book is primarily based on assumptions without referring to primary sources, as some skeptics claim?

M. Z.: Those who think in such a way might not be well aware of the nuances of Russia’s political journalism. In fact, since the beginning of the 2000s, there hasn’t been [reliable] information based on primary and open sources in Russia’s political press. If you open high-quality newspapers in Russia such as Vedomosti or Kommersant, all journalistic investigations are based on anonymous sources. This is the reality that has existed in Russia for more than 10 years. And there is no other reality.

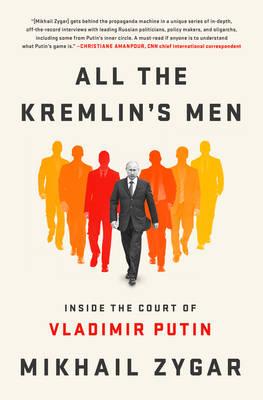

“All the Kremlin’s Men: Inside the Court of Vladimir Putin” will be published in English in September “All the Kremlin’s Men: Inside the Court of Vladimir Putin” will be published in English in September |

In such a situation, I had several alternatives: Either I could give up writing the book or I could write an official and boring account about Russian politics or Putin, which would be released but would fail to attract an audience, because it would not reflect the reality.

Another option was to come up with the book that I wrote, one based on off-the-record conversations. At the same time, the book contains references to primary sources; in fact, I clearly identified them in my book and mentioned many interviewees.

Nevertheless, although almost the entire book is based on anonymous sources and on their narratives, I don’t see it as a flaw; instead, I see it as an advantage, because this is the only opportunity [in Russia] to find out true information about what is happening behind the scenes of Russia’s politics.

RD: The structure of your book is based on the comparison of each of Putin’s tenures with different historical monarchs — from Richard the Lionheart to Ivan the Terrible and, finally, to Vladimir the Saint. How can you account for this?

M.Z.: It’s rather an irony: It’s about the [psychological and behavioral] changes inside one person; it’s about the changes in his mindset, his outlook, his self-assessment; it’s about the changes in how others — his environment — treat him. And all these changes can be so drastic, I mean, beyond recognition.

RD: Some compare your book with the one by New York Times reporter Steven Lee Myers (The New Tsar: The Rise and Reign of Vladimir Putin), despite the fact that your books offer totally different explanations of Russia’s politics and alternative narratives. You argue that there is no intention in what happens in Russia, that Russia’s politics are situational in nature and respond to domestic and foreign challenges depending on circumstances. In contrast, Myers seems to search for an explanation in the intentional schemes in Putin’s behavior and Russia’s politics: Everything is predetermined and has a certain design. Why do you avoid such an approach?

M.Z.: If you compare my book with the one by Steven Lee Myers, it’s important to keep in mind that they’re written in different genres. While he wrote a book about Putin, I came up with a book not about Putin per se. The main character of my book is the collective environment around Putin; it is rather about the Russian system of power.

It is not the biography of a person. And if you write the biography of this person, everything should be related to this person. Involuntarily or purposely, you may either idealize or demonize him; you put him in the center of the world. I see such an approach as a key mistake, committed by about 99 percent of both Russian and foreign journalists who write about Putin.

"By demonizing and idealizing Putin, many journalists have come to wrong conclusions in an attempt to follow the rules of the genre they choose." Source: Reuters

"By demonizing and idealizing Putin, many journalists have come to wrong conclusions in an attempt to follow the rules of the genre they choose." Source: Reuters

Unfortunately, they purposely distort the reality just because they put themselves in the framework of the genre that they choose. Instead of trying to describe the real political processes, they draw the same artificial and improbable schemes. After all, never ever does life add up to a simple black-and-white picture; I firmly believe that it is more nuanced.

To illustrate this, I always give an example: During numerous sessions in the beginning of Putin’s first tenure, the Russian president frequently reiterated that Russia needed to take care of Ukraine otherwise Moscow would lose it. It is a clear indication that reveals his initial plan. It was to control Ukraine, not to alienate it by incorporating Crimea.

RD: Your book looks like a counterbalance to the numerous conspiracy theories that abound today in Russia and abroad. Why do you think they are popular among the Russian political elite? Do they really believe in conspiracy theories or don’t they — maybe they just use them to manipulate and impose their own agenda?

M.Z.: Based on my numerous conversations with key Russian politicians and officials, I would argue that many of them do believe in conspiracy theories just because it is such an easy answer to difficult questions. They just see it as a simple and logical explanation: that we are right, while others are wrong; or even though we are wrong, it is not our fault — it is the fault and plot of our enemies. Yet such behavior is common not only for Russian politicians, but also for their foreign counterparts.

It seems to me that the explanation that presents Putin as a politician with an artful and skillful plan to conquer the world, is another example of a conspiracy theory that is very popular in the West. For example, some Western journalists frequently ask me why I don’t pay attention [in my book] to a special operation by the Federal Security Service (FSB), which allegedly sought to integrate then-agent Putin into the structures of Russian government and, afterwards, take over all its institutions. This is a good example of a fantastical conspiracy that is unfortunately in vogue among foreign journalists. Alas, it usually hampers a well-balanced and reasonable analysis.RD: Some argue that there is a demand for paternalism in Russia, which means that Russians are not ready for true democracy. However, it is not clear what comes first – the demand for a paternalistic leader from the population or the Kremlin’s information campaign that imposes this agenda. It’s like the chicken and egg problem. What’s your take on it?

M.Z.: This is the very question that preoccupied people in the early 20th century, during the events that preceded the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution (I’m now writing a book on this historical period in Russia). Likewise, they were debating the question of whether the Russian people were ready for democracy or not. Interestingly, in 100 years these doubts – whether Russians are ready or not – still persist. In my view any claims that Russians are not ready for democracy are very dubious: It’s an attempt to ascribe anthropomorphous, human characteristics to inanimate objects like entire nations.

In my view, Russian society is much more sophisticated and it brings together different groups of peoples with different values. While some stick to democratic values, others prefer to affiliate themselves with a great power and share imperialistic values, they feel pride for their country. These people are very different in their mindset.

At the same time, there is a group of people who are politically apathetic, who try to shy away from politics and power; they are preoccupied with routine, mundane burdens and they don’t think about democracy; they just don’t want to be bothered. And such people represent the majority of the population.

This is an abridged version of the interview first published by Russia Direct. Click here to read the full version.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox