Stalin’s terror: Should the names of NKVD executioners be made public?

Joseph Stalin and his People's Commissars standing on the tribune of Lenin's Mausoleum during a Parade of Athletes.

TASS“Breaking news! We have found them all! All!” wrote Denis Karagodin, a 34-year-old philosophy graduate from the city of Tomsk in Western Siberia, in mid-November on a website devoted to his great-grandfather, who had been executed during Stalin’s purges of the 1930s.

In the post, Karagodin revealed that he had managed to obtain from the FSB (Federal Security Service) archive a report about the execution of 36 people, among whom was his great-grandfather Stepan. Most importantly, according to Karagodin, the document contained “the names of the immediate (ultimate) murderers,” the NKVD (interior ministry) officers who executed his great-grandfather.

Having studied Karagodin’s research, a descendant of one of the officers recognized her grandfather. She wrote to Karagodin, asking for forgiveness and telling him that her family members had been subjected to reprisals too.

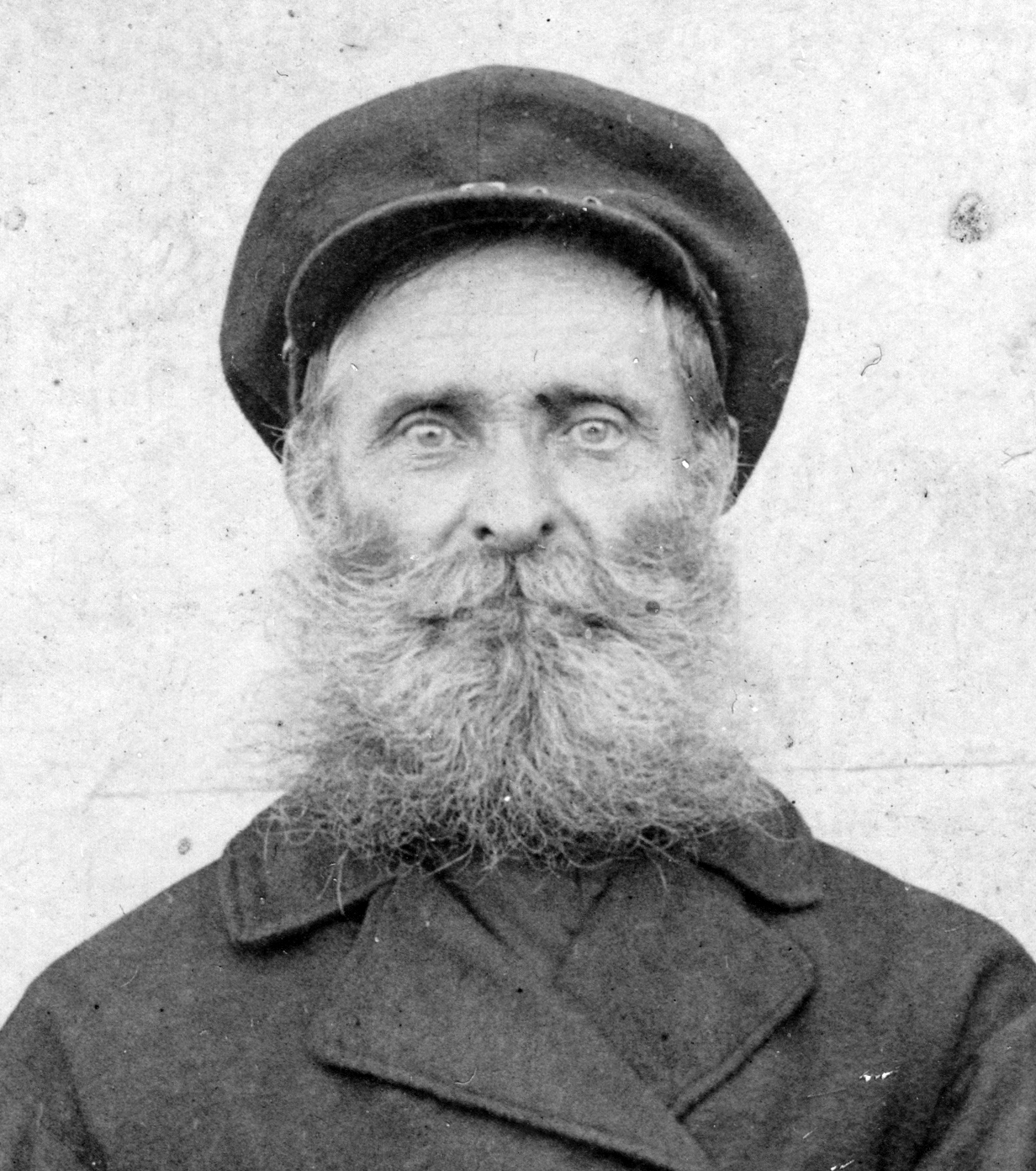

Karagodin Stepan Ivanovich. Source: blog.stepanivanovichkaragodin.org

Karagodin Stepan Ivanovich. Source: blog.stepanivanovichkaragodin.org

The story provoked a lively online discussion as to whether there is any point in trying to identify those who executed people during the purges and make their names public, especially since all of them are long dead, or whether it would be best to forgive everyone, recognizing that their descendants are not responsible for what the previous generation did and that this tragedy – one way or another – touched everyone.

List of executioners

Stepan Karagodin, a peasant, was arrested by NKVD officers in Tomsk in 1937, during the Great Purge. He was tried by a so-called dvoika (a “pair”: a senior NKVD officer and a prosecutor) and sentenced to death as a Japanese spy and an organizer of an espionage and saboteur group. The sentence was carried out in January of the following year. In the late 1950s, during the Khrushchev Thaw and destalinization, Stepan Karagodin was fully rehabilitated.

Karagodin's family. Source: blog.stepanivanovichkaragodin.org

Karagodin's family. Source: blog.stepanivanovichkaragodin.org

Denis Karagodin first began looking for his great-grandfather’s killers back in 2012. He sent inquiries to different archives and ultimately compiled a list of killers comprising dozens of names. As “the masterminds of the murder,” the list names members of the senior Soviet leadership: Stalin, Molotov, Voroshilov and others. The list also features people at much lower levels too, for example, an NKVD driver.

Karagodin is convinced that responsibility for his great-grandfather’s killing lies on everybody involved, even the typists who typed the relevant NKVD documents. Next to some names, there are special markings, the findings of the investigation – “CONFIMED! EXECUTIONER!” in big red letters.

The key document – the report that the death sentence had been carried out by the Tomsk city directorate of the NKVD – reached Karagodin only in November this year, after a second request sent to the FSB’s Novosibirsk Region directorate. The report had been signed by three people.

Source: blog.stepanivanovichkaragodin.org

Source: blog.stepanivanovichkaragodin.org

Karagodin, “on the basis of contextual and cumulative knowledge,” as well as his belief that “those who drew up that order were the ones who carried it out,” describes all three men as executioners, those who directly pulled the trigger. The first signature is that of Nikolai Zyryanov, an aide to the head of the Tomsk prison.

‘I extend you my hand in reconciliation’

News about Karagodin’s search and findings was widely shared on social networks, and soon he heard from Zyryanov’s granddaughter Yuliya, who gave her permission for Karagodin to use .

“I haven’t been able to sleep for several days, I just can’t… […] I am very ashamed about everything. I physically feel this pain. I bitterly regret that there is nothing I can do to make amends apart from admit to being a relative of N.I. Zyryanov and remember your great-grandfather in my prayers,” the NKVD officer’s descendant said in her letter, as quoted by Karagodin.

She added that her great-grandfather on her mother’s side had also been killed in the purges – “thus, there were victims and executioners within one family.” In his reply addressed to “the granddaughter of the executioner who killed Stepan Karagodin,” his great-grandson said: “I extend you my hand in reconciliation, no matter how hard it is for me to do it.”

Source: blog.stepanivanovichkaragodin.orgNow Karagodin wants to secure posthumous criminal prosecutions for those whom he calls his great-grandfather’s killers. The list contains 20 names: from Joseph Stalin to an NKVD driver, who “will be prosecuted as an accomplice.” “The charge is: a conspiracy to commit mass murder,” said Karagodin.

Source: blog.stepanivanovichkaragodin.orgNow Karagodin wants to secure posthumous criminal prosecutions for those whom he calls his great-grandfather’s killers. The list contains 20 names: from Joseph Stalin to an NKVD driver, who “will be prosecuted as an accomplice.” “The charge is: a conspiracy to commit mass murder,” said Karagodin.

‘Evil should be forgotten’

Karagodin’s story has triggered a lively public debate in Russia. Many describe his investigation as a watershed moment. According to Stanislav Kucher, an observer with the Kommersant FM radio station, Karagodin’s attempt to launch a criminal case against his great-grandfather’s killers is “a historic event with serious political repercussions.”

“…Until now, no-one has thought of seeking criminal prosecution for Stalin’s state with a Criminal Code in their hands, through a personal investigation and bringing a personal action over the death of a family member. It is symbolic – and as far as I am concerned, heartening – that this way of tackling the question of ‘whether Stalin was good or bad’ was proposed by a smart guy from the generation of the 2000s,” Kucher said.Yet, there are also those who, while accepting that finding out one’s great-grandfather’s fate is a worthy thing to do, believe that in compiling his list of executioners Karagodin went too far.

In the opinion of columnist Dmitry Olshansky, whose great-grandfather too was executed on trumped-up charges during the purges, “nobody can be brought back” and “nothing in what happened can be changed.” He is convinced that “there can be no responsibility and repentance through generations,” adding that repentance can be “only for one’s own deeds.”

“…I think it is too late to punish my great-grandfather’s killers. I think evil should be forgotten. Totally, finally, that’s it,” wrote Olshansky.

Subscribe to get the hand picked best stories every week

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox