Cold War archive: How the USSR and U.S. battled each other with radio waves

A group of State Department announcers huddle around the microphone after the initial shortwave broadcast in Russian to Russia from New York City on Feb. 17, 1947. The announcers, Russian-born American citizens, are (front row) Boris Brodenov; James Schigorin; Elena Bates (seated); Victor Franzusoff; (rear row) Katherine Elene; Vladimir Postman and Tatiana Hecker. Sign in Russian on the microphone means "The Voice of the United States of America."

AP A group of State Department announcers huddle around the microphone after the initial shortwave broadcast in Russian to Russia from New York City on Feb. 17, 1947. The announcers, Russian-born American citizens, are (front row) Boris Brodenov; James Schigorin; Elena Bates (seated); Victor Franzusoff; (rear row) Katherine Elene; Vladimir Postman and Tatiana Hecker. Sign in Russian on the microphone means "The Voice of the United States of America." Source: AP

A group of State Department announcers huddle around the microphone after the initial shortwave broadcast in Russian to Russia from New York City on Feb. 17, 1947. The announcers, Russian-born American citizens, are (front row) Boris Brodenov; James Schigorin; Elena Bates (seated); Victor Franzusoff; (rear row) Katherine Elene; Vladimir Postman and Tatiana Hecker. Sign in Russian on the microphone means "The Voice of the United States of America." Source: AP

"Hello! This is New York calling. You are listening to the first radio broadcast of Voice of the United States of America." These words were heard on the radio in the USSR for the first time on Feb. 17, 1947, one year after the start of the Cold War.

Known simply as Voice of America, or VOA, this was the first American state-run radio station to start daily broadcasts in Russian.

During the first transmission announcers stated the purpose of their radio station: "To give listeners in the USSR a picture of American life" and to develop friendship between the Soviet and American peoples. Be that as it may, the Communist Party (CPSU) didn't believe in Washington’s friendly intentions, and by 1948 it started jamming the radio station.

Enemy voices

The position of the Soviet authorities was unequivocal - Western radio stations brainwash Soviet people with propaganda, and Soviet people are not allowed to listen to them. Special jamming stations were built around the country to block the frequencies on which the "enemy voices" were broadcasting. By the early 1960s, the number of Soviet jamming stations had reached 1,400.

Journalist Oleg Rogov, who grew up in the Soviet Union, recalls that "jammers" worked poorly at night, and so those who wanted to listen to alternative information would sit by their radio receivers in the evening, trying to find the frequencies on which they could hear something. Another way to listen to a Western radio station was to get away from the big cities; there were fewer "jammers" in rural areas.

People could often listen to Voice of America, Radio Liberty or BBC in the countryside or even on a beach. Another way was to buy a shortwave radio, but they were much more expensive than conventional transistor radios, and anyway, they often aroused suspicion from law-enforcement.

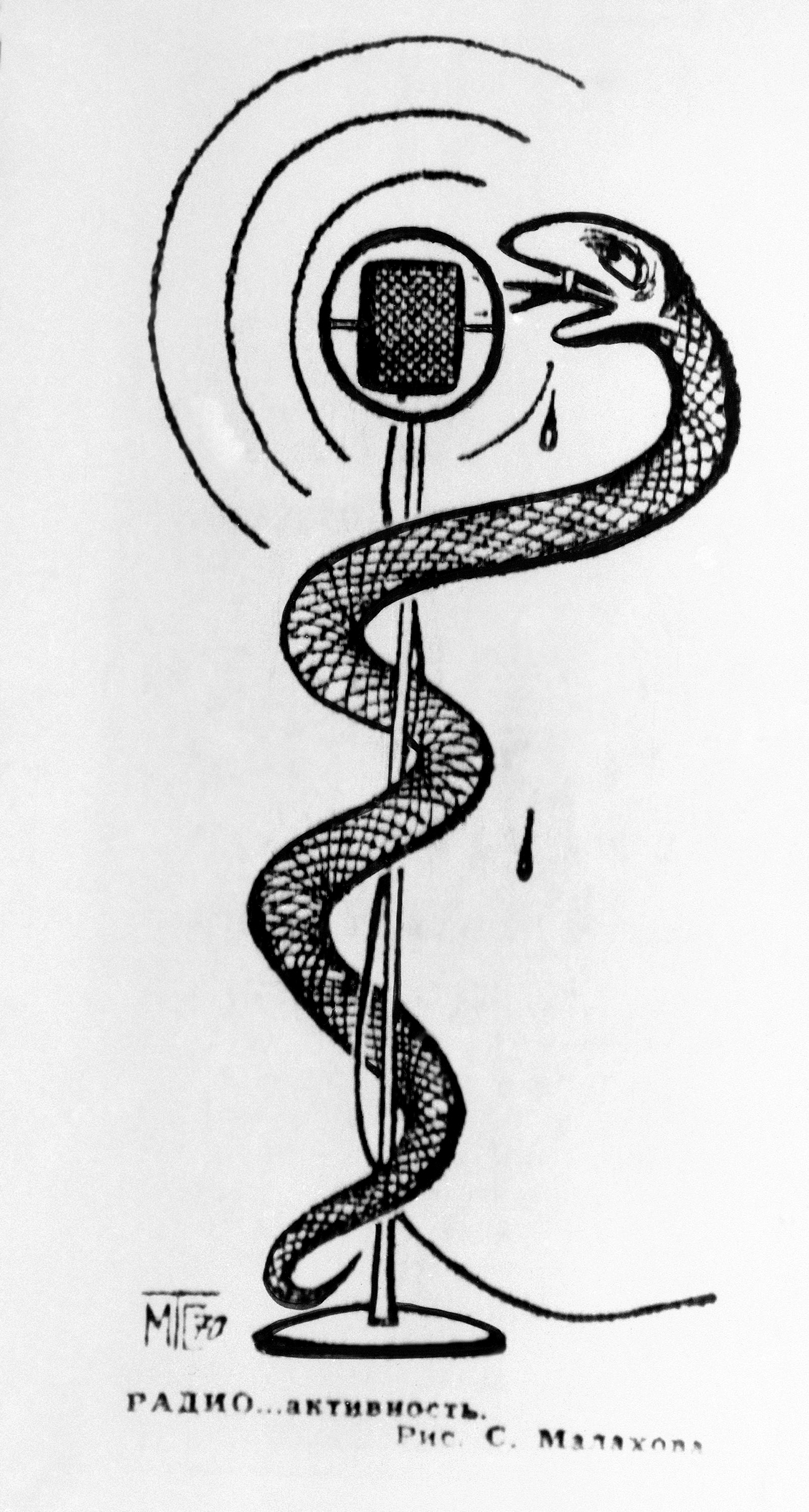

This cartoon titled “Radio-Activity” appeared in the newspaper Soviet Estonia on Jan. 24, 1970 as part of the Soviet press campaign against the daily broadcasts of the voice of America. Source: AP

This cartoon titled “Radio-Activity” appeared in the newspaper Soviet Estonia on Jan. 24, 1970 as part of the Soviet press campaign against the daily broadcasts of the voice of America. Source: AP

Ideological war

"American radio broadcasting is not a gift to the world in any way, but rather it is a tool of international politics to spread democratic values," said media analyst Donald Jensen, assessing Voice of America, and admitting that VOA played the role of a propaganda weapon in the fight against communism.

Many people in the Soviet Union regarded "enemy voices" as an alternative viewpoint, and so this viewpoint was interesting. "We did not trust the Soviet media - reading Soviet newspapers was boring," recalled Pavel Balditsyn, a professor at Moscow State University. "Of course, it was interesting to hear voices from the outside, albeit they too were perceived as propaganda."

Balditsyn said that those in the USSR who secretly listened to and discussed what they heard on Western radio stations also doubted the content because they were accustomed to homegrown propaganda.

"But Voice of America broadcasts were seen as more or less trustworthy," he said. The news website, Lenta.ru, reported that VOA was the most popular of all the "enemy voices," with an audience of 30 million people each week.

Solzhenitsyn and jazz

VOA was interesting not only because of its different political viewpoint. Listeners remember how they turned the dials on their receivers to hear music or literary programs. Balditsyn recalls that once when on duty at night while serving in the army he listened to Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s The Gulag Archipelago, which was banned in the USSR and only officially published in 1990.

Human rights activist Boris Pustyntsev said his love for jazz started with VOA broadcasts. "Swing, early bebop and so on," recalled Pustyntsev. "I could not even go to sleep without first listening to the latest music program."

"Swing, early bebop and so on," recalled Pustyntsev. "I could not even go to sleep without first listening to the latest music program." Photo: Two men listen to radio in the Soviet Union on April 1, 1958. Source: TASS

"Swing, early bebop and so on," recalled Pustyntsev. "I could not even go to sleep without first listening to the latest music program." Photo: Two men listen to radio in the Soviet Union on April 1, 1958. Source: TASS

Mission accomplished

VOA’s fate was closely linked to politics, and as soon as relations with the U.S. thawed the "jammers" worked less intensively or were switched off altogether. This was the case during the detente between the superpowers in the second half of the 1970s, and up to the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan when relations worsened and transmissions were again subjected to jamming.

The fight against "enemy voices" completely ceased under Mikhail Gorbachev in 1986 with a special resolution of the Communist Party. VOA transmissions were now allowed in the USSR, but five years later in 1991 the Soviet Union collapsed and that was the beginning of the end for the once-forbidden radio station. The end of the Cold War also meant the end of VOA’s glory days. The U.S. propaganda radio station had more or less accomplished its mission.

By 1992 Russia had freedom of the press, alternative sources of information appeared, and overall interest in radio transmissions declined. In July 2007 VOA’s Russian Service stopped broadcasting and switched entirely to the Internet.

Read more: The untold story: Why Stalin created a cult of Alexander Pushkin>>>

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox