Jousting with Jehovah: Russia bans American church

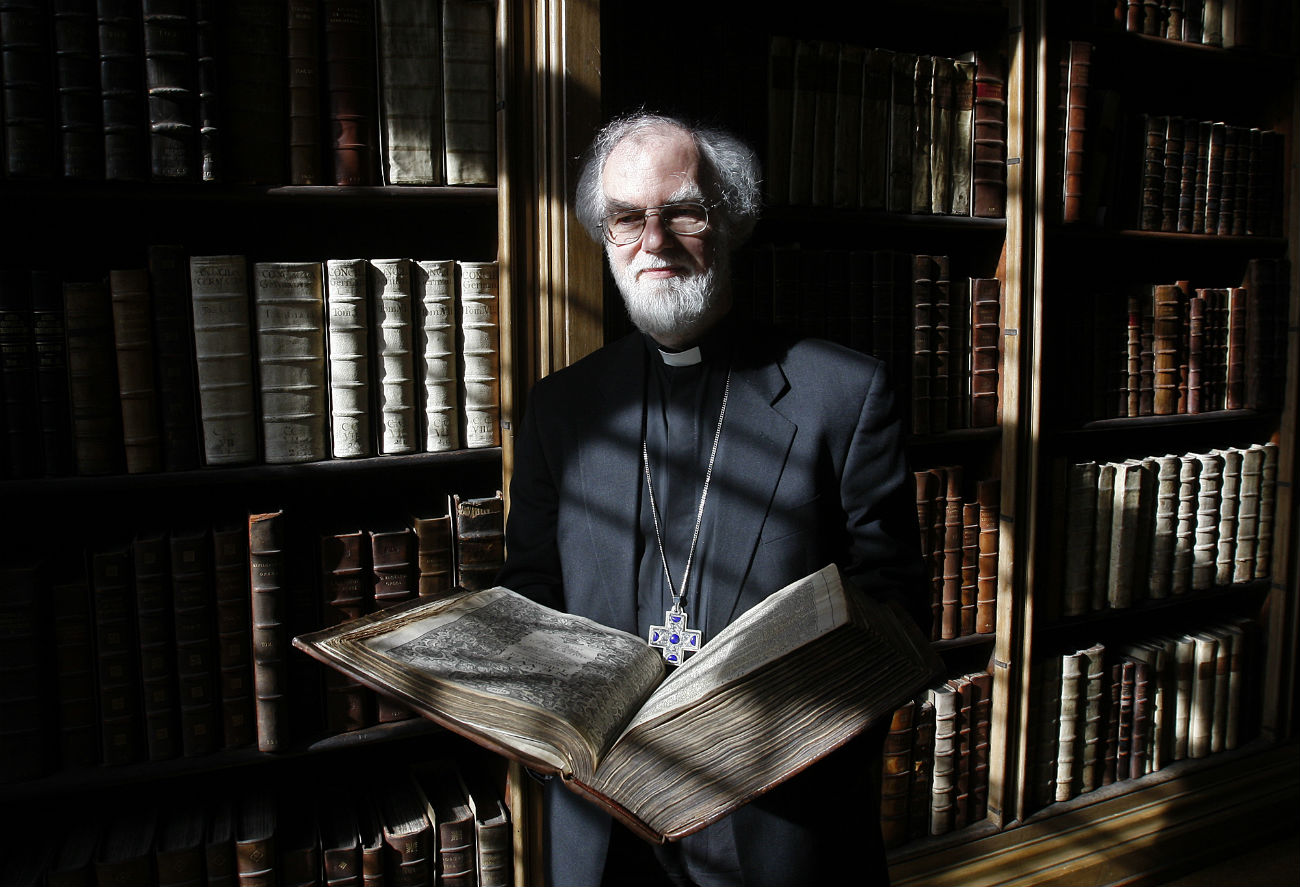

Members of Jehovah’s Witnesses attend a church service.

Getty Images Members of Jehovah’s Witnesses attend a church service. Source: Getty Images

Members of Jehovah’s Witnesses attend a church service. Source: Getty Images

Russian authorities never had warm feelings towards Jehovah’s Witnesses. A different interpretation of numerous Scripture passages is one of the things setting them apart from the Russian Orthodox Church.

At best, during the past century Jehovah’s Witnesses were ignored in Russia. At worse, they were banned, and Stalin in 1951 even exiled 8,000 of them to Siberia, which was 80 percent their total number in the Soviet Union at the time.

Jehovah’s Witnesses, however, consider the most recent attack even more serious because they've been outlawed and labeled a dangerous organization.

Today, their ranks total about 165,000 in Russia, according to data gathered by Roman Silantiev, deputy head of the Justice Ministry's Council for State Religious Expertise.

In recent years, several regional congregations of Jehovah’s Witnesses have been shut down entirely, and over 60 of their publications were labeled "extremist materials." On March 15, Russia's Justice Ministry filed suit with the Supreme Court asking to ban the organization as an extremist group.

The Justice Ministry explained to RBTH that the accusation centers on printed materials that allegedly proclaim Jehovah’s Witnesses’ supremacy over other religions and justify violence towards followers of other faiths. On the same day, Deputy Justice Minister Sergey Gerasimov ordered a suspension of all Jehovah’s Witnesses activities in the country until the court’s ruling.

The main argument presented during the hearing, which lasted almost a month, was dozens of court rulings against Jehovah’s Witnesses' regional offices that saw no reaction from the church's headquarters, the so-called Administrative Center.

Lawyers representing the church stressed that regional congregations do not report to the center, therefore complaints against them cannot be the basis for banning all Jehovah’s Witnesses. Moreover, the Administrative Center was never involved in those hearings and never received any warnings from the Justice Ministry.

The Administrative Center, however, stopped bringing printed materials to Russia that were listed as extremist literature in the lawsuits. The attempt to ban the organization surprised even the most loyal officials and public figures.

Maxim Shevchenko, a member of the Presidential Council for Civil Society and Human Rights, and also president of the Center for Strategic Studies of Religion and Politics of the Modern World, said the lawsuit filed by the Justice Ministry goes against the fundamental principles of freedom of thought.

"Jehovah’s Witnesses are hardly an extremist organization," he said. "They never organized terrorist attacks or called for unlawful actions. They're often accused of presenting their religion as the ultimate truth, but many churches do that. I think the real reason for this persecution is the fact that they appeal to people directly, preach face-to-face, thus competing with the Russian Orthodox Church in some regions. Obviously, the Moscow Patriarchate and top security officials connected to it are behind the whole affair.”

A kingdom well-guarded

The Russian “Administrative Center of Jehovah’s Witnesses” is located in St. Petersburg. I called them while the trial was underway, but just after the suspension order issued by the Justice Ministry. I dialed the number that I found on their website, and to my surprise the office was open and a friendly male voice greeted me on the other end.

I told him that I wanted to attend a Jehovah’s Witnesses gathering in Moscow. Even though suspension meant cancelling all meetings, the man gave me an address in Moscow: 36 Mikhalkovskaya Street, "every Saturday and Sunday."

So I went to this address on a weekend, and which is just a short walk from the Koptevo metro station, seven miles from the Kremlin. There, I found a two-storey facility built in the 1920s for a textile factory, and which had been a community center for the workers. Now it's private property, according to Rosreestr.

They call it Kingdom Hall, and it's obvious that Jehovah’s Witnesses own the whole building. There's a line of several dozen people in front of it. Security dress in black suits (they are also members of the congregation), and they soon became suspicious, pulled me aside and questioned me about the purpose of my visit. But then they let me in.

During church services adherents listen to sermons and the teachings of Jehovah, and also sing. Source: Getty Images

During church services adherents listen to sermons and the teachings of Jehovah, and also sing. Source: Getty Images

After checking my coat, I walk into a hall that seats 300 people. It's almost full, and I have a hard time finding a seat in one of the back rows. Before I have a chance to sit down I’m approached by an usher, Anatoly, (that’s what his name tag said). He conducts a 10-minute interrogation, asking everything about me, where I live, and if I'm a journalist. In fact, I'm the only journalist in the room, and I'm undercover.

Anatoly tells me not to take pictures, but I snap a few photos with my phone. He also asks how I found out about the gathering. Well, I'm very lucky because this isn't just a regular church service; this is a special convention that takes place twice a year, with the entire leadership in attendance.

In this hall - apparently it was the small hall - we only see the video feed projected on the screen, whereas the meeting itself is in the main hall on the second floor, where there are even more people. Anatoly seems satisfied with my answers, but strongly recommends seeing him after the convention.

Gratitude without borders

The screen shows two men sitting on the stage opposite each other, acting out a scene – a conversation between two brothers. The younger brother’s wife is seriously ill and needs a blood transfusion, which is strictly forbidden to members; so the brother has come for advice.

"I need help from someone with a clear mind." The conversation ends with the elder brother instructing his sibling: "The most important thing is keep faith in Jehovah. Even if a person dies, Jehovah can bring him or her back to life." The audience is clapping.

Almost everyone is holding a Bible and a notebook to take notes. The last speech draws special attention – it's by Nikolay, a traveling overseer. In the Jehovah's Witnesses hierarchy a traveling overseer supervises several local congregations, each comprising between 50 and 100 people, and instructs his followers, while living off of their donations.

Nikolay looks like a Komsomol member - a groomed young man with bright eyes. He makes long theatrical pauses and talks in a dramatic voice about the gravest sins of all – that of disbelief – and how to avoid it. Nikolai warns the congregation: "Very soon Jehovah will destroy the old world – the world of injustice – and only those who didn't stray from the path of faith will be rewarded in full."

At the end of his speech, Nikolai cues the congregation to start singing "Song 43" ("Stay Awake, Stand Firm, Grow Mighty"), which sounds a lot like La Marseillaise. After that, the overseer addressed the audience with a question: "Shall we give a modest offering to those who organized this convention as an expression of our gratitude?" There's a storm of applause.

Inside the hall are two large boxes with signs reading, "donations for the global cause." Rank and file members, who, to be fair, looked neither frightened nor hypnotized, voluntarily put money into the boxes. I couldn't find out the total amount, but many people were very generous in their donations, offering between 1,000 and 5,000 rubles (about $17 to $88, respectively).

A Russian woman at a street stand offering Jehovah’s Witnesses' literature. Source: Alexander Artemenkov / TASS

A Russian woman at a street stand offering Jehovah’s Witnesses' literature. Source: Alexander Artemenkov / TASS

Apocalypse today

As I go out into the street, Anatoly the usher confronts me. He asks if I'd like to know more about Jehovah's Witnesses and whether I was married. Later, I learn that even potential members are advised against marriage to an unbeliever. Then, we exchange telephone numbers.

I also got acquainted with Ekaterina, a middle-aged woman, and we agreed to go to one of a Jehovah's Witnesses tea parties, which are home gatherings held every weekend. She says the church prohibits many things: you cannot hold a government job, participate in protests and rallies (both opposition and pro-government), serve in the army, stand for the national anthem, and even moan during sex.

I asked Ekaterina how she became a member and she answers that many years ago, after she was beaten by her stepfather, she was sitting on the floor in despair, praying to God. At that moment the doorbell rang – it was the Jehovah's Witnesses. She took two books from them, which changed her life, and her stepfather’s life. Now they go from apartment to apartment together, telling people about Jehovah's Witnesses and offering books.

Whether true or not, this is a typical initiation story that you can hear from almost any follower. The founder of Jehovah's Witnesses, the American judge Joseph Rutherford, wrote that he came to this new faith in a similar way - while studying to become a lawyer, he worked part-time selling books. His potential customers often told him to get lost, so he made a promise that one day, when he would earn good money, he'd definitely buy books from a young salesman.

He eventually fulfilled his promise, and the books he bought happened to be Bible study textbooks. Rutherford saw this as a sign and devoted himself fully to the service of God.

Ekaterina also said she doesn’t earn a penny giving out the books – in fact, every month she donates $50 to $100 for the“global cause." She didn't ask anything of me – although, to be fair, I never went to the “tea party” as promised. Over the next few days, Ekaterina pestered me incessantly with text messages that would seem complete nonsense to the uninitiated:

"Don’t feel bitter. With us, all prophecies come true." "What I tried to tell you is Revelation in its original form. The Antichrist is already among us, the countdown has started." "Just so you know: all five Terminator movies were filmed by American Messianic Jews." "I've known the truth for 20 years, and they are still trying to send me to an insane asylum because of this."

On the day of the terrorist attack in St. Petersburg she wrote to me: "Revelation, chapter 15:2. Read it. It talks about the sea of glass and fire." There is nothing extremist about her – she just seems to have a mental disorder.

"We won't give up"

There have always been debates about whether Jehovah's Witnesses are a sect or just a group of scam artists. But now they face criminal prosecution for a completely different crime, and which is punishable by up to six years imprisonment. Meanwhile, Vladimir Ryakhovsky, a member of the Expert Council of the State Duma Committee on Public Associations and Religious Organizations, believes persecution is inevitable.

"A lot of people are saying that it's unlikely to happen; well, I say this is bound to happen. In 2009, they banned the local congregation in Taganrog, and then in 2012 they took police footage, recorded a service was and started a criminal case, which lasted for quite a long time," said Ryakhovsky. "The verdicts started coming only by the end of 2015. Sure, there were only fines and suspended sentences, but these were all convictions, and now it’s getting even worse. This time, it’s not just about a single congregation. It's about all of Russia."

I called Anatoly the usher. "What are you going to do now that the court has banned Jehovah's Witnesses for good?"

"We will pray to God," he replied. "Everyone who ever tried to hurt us has ended up in misery. Hitler wanted to burn us in his ovens; Stalin wanted to send us to rot in Siberia – and where are they now? They are cursed – and we live. We will survive. We are not going to give up."

I asked him, "How exactly are you going to not give up?" But Anatoly gave no reply. The Jehovah's Witnesses leadership, he said, will appeal the Supreme Court decision. They have a month to do that – and will do it without any violence or extremism.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox