Brief history of corruption in Imperial Russia

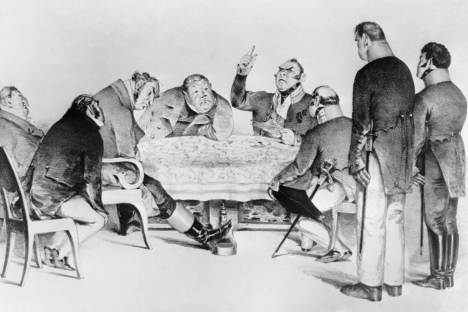

The Government Inspector (Revizor in Russian) by the writer Nikolai Gogol is a comedy of errors satirizing human greed, stupidity, and the extensive political corruption of Imperial Russia. Source: ITAR-TASS

The third presidential term of Vladimir Putin has been marked by an unprecedented (for post-Soviet Russia) war on corrupt officials in the central governing apparatus and in the regions. The visible advance in that direction began during Putin’s second term, in 2006, when Russia ratified the U.N. Convention against Corruption and was thus internationally obliged to employ effective measures against illicit profits and tax fraud.

A second significant step was taken under the rule of Dmitri Medvedev in 2008, when the National Plan of Corruption Resistance was signed. Ironically enough, it was in the late 2000s that the amount of bribes discovered by the Investigative Committee of Russia steeply increased—from 6,700 cases in 2007 to 8,000 in 2008, peaking at a figure of 13,100 in 2009.

To understand what anti-corruption measures have proved successful in the past, it is necessary to make a brief overview of the history of bribery and abuse of official position in Imperial Russia.

In medieval Russia, bribes existed only in court, where senior comrades of the ruling princes—or, in central regions of the land, the princes themselves—sat in as judges. With the consolidation of power in Moscow, which started in the late 15th century, the centralized state began to emerge, bringing about the need to control and defend the border towns, which were prone to attacks by the Tatar nomad cavalry.

During the 15th and 16th centuries, the Great Princes of Moscow sent their officials to act as governors of those faraway parts.

The governors received no salary: In lieu of this, they received goods and food from the local folk, by way of a practice known as “kormlenie” (literally “feeding”).

The necessity of these “feedings” arose from geographical and economical factors—the physical lack of money, which was mainly used for foreign trade, and the great distances that divided the center and the regions. The salaries would never arrive on time; sometimes they would not arrive at all, as the messengers would get robbed by rogues on the road.

Kormlenie was sanctioned by the state power and could be extorted if the locals would refuse to give it. This habit not only prepared the ground for the growth of corruption, but also, in the minds of Russian people, it planted the notion of the practice of government officials accepting goods and food as an intrinsic feature of the Russian governing system.

With the development of the state and the emergence of the first administrative departments (known as “prikazy,” or “orders”), corruption rose to a new level. In mid-17th century, there were over 50 judicial, territorial and executive orders subordinate to the main governing body of the state—the Boyar Duma. This body was a council of noble military commanders, fellows to the czar and, often, corrupt officials themselves.

Related:

How far will the Kremlin’s corruption crackdown go?

Corruption in Russia can be solved given the will

Over 6,000 people were convicted for corruption in Russia in 2012

The boyars, who governed the orders through subordinate officials (“dyaks”), were themselves obliged to control the expenses, which rendered the control function useless.

The growth of corruption and the elevation of taxes finally led to the first anti-corruption riot in Russian history, which was known as the Salt Riot of 1648. Czar Alexey Mikhailovitch, who was 19 at the time of the riot, learned that, to control corruption, an independent office had to be set up.

The Privy Order, which emerged around 1653, included the functions of the czar’s private chancellery and supervision institution, and was subordinate only to the head of the state.

None of the boyars were involved in the order’s affairs; the officials of the order investigated notable cases of bribery, theft and crimes against the state and the czar. The Privy Order, abolished after the death of Alexey Mikhailovitch, is considered to be the first control institution in Russian history.

{***}

The reforms of Peter the Great brought drastic changes to Russian government—the Boyar Duma was dissolved, the orders were replaced by collegiums. With established salaries, there was no longer a need for “feedings”; thus, accepting any kind of bribe by a government official became a crime.

On the other hand, the building of new cities and the need for supplies for the army involved in the war with Sweden opened a vast range of opportunities for theft. Corruption rose to painful levels, with Prince Menshikov, the czar’s closest counselor and right-hand man, being the most prominent thief.

“I have but one right hand, and it steals,” Peter complained. Peter’s measures against corruption were numerous; all departments were obliged to submit annual reports to the Governing Senate, which was the highest collegial governing body. Since 1722, the Senate was charged with conducting revisions of local institutions, in order to reveal and punish corrupt officials.

In addition, the post of Prosecutor General was established. Unfortunately, after Peter’s death, little attention was paid to his orders: The Senate received no reports, prosecutors mainly concentrated on political trials, and only one thorough revision took place in 1726.

Russian nobility, which gained incredible power through the course of the 18th century, was not interested in maintaining a solid anti-corruption program that would stand in the way of the nobility’s own benefits.

It is no wonder that, from 1726 to the end of the 18th century, no Senate revisions took place. The Prosecutor General, also in charge of investigating crimes against the state and directed domestic politics in the fields of justice and finances, had very little time to fight corruption on a national scale.

The change came about during the reign of Pavel I, who on October 6, 1799, ordered the senators to conduct a thorough revision of the empire’s institutions.

The results were astonishing: Hundreds of corrupt officials were replaced and incarcerated. The revision brought about a significant hastening of paper work in the regions, and the central power received a great deal of information about the real state of affairs in the country.

Over the course of the years, the Senate revisions proved to be the most effective tool in fighting corruption. During the first half of the 19th century, over 80 revisions took place; some regions were revised two or three times. The senators stayed in the regions for months and even years, collecting complaints from the local people and writing reports.

The senators had no relations to local officials and were impossible to bribe—they were too rich! Most of the senators knew the emperor in person, so their reports bypassed the institutions and offered the emperor a first-hand account of the state affairs. The Senate revisions greatly intimidated corrupt officials and invigorated local administrative affairs.

However, this situation did not last long. After the death of Nicholas I, the amount of regular revisions significantly decreased.

Certainly, the state created different offices (most notably, the Third Section of His Imperial Majesty's Own Chancellery) to supervise the civil and military service and fight corruption, but their main drawback was their location: With headquarters situated in the capital, they lacked presence in the regions, which was a problem that had been solved by the Senate revisions.

Furthermore, the central offices specialized mainly in large-scale corruption, while day-to-day bribery in the regions remained unpunished. Eventually, the situation worsened to the point that corruption in the army and among the highest officials had been cited as the main reason for the defeat in the Russian-Japanese war.

The history of anti-corruption measures in the Soviet Union is subject to a separate overview; nevertheless, certain conclusions can be made using the example of the Russian Empire.

This short survey shows that anti-corruption measures work best when they are carried out by high-ranking officials who: are not prone to large bribes because of their own wealth; are subordinate to the head of the state; carry private responsibility for the results of their actions. Bodily presence of officials is also crucial for the effectiveness of investigation.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox