Memoirs of a covert Soviet soldier in the Korean War

The participation of Soviet pilots in the Korean war was made public in the Soviet Union only in the 1970-1980s.

U.S. Army Center for Military HistoryNikolay Melteshinov is very pleased with his brief military career. In October 1952, he was honored to serve his mother country once again: “The Great Patriotic War” (as World War II is known as in Russia) had ended, and he, being still a young but experienced anti-aircraft artilleryman, was offered a special mission to perform.

At the Khabarovsk Military Garrison, they made him sign a pledge of secrecy, but, according to Melteshinov, many already knew what was going on. Having received his identification badge and becoming part of the 76-mm anti-aircraft gun division, he went by train to his mission.

At that time, he was not interested in politics; he did not ask why or where. At the transshipment point in the border town of Grodekovo, he exchanged his Soviet officer uniform to a Chinese military tunic.

A total of 64 fighter air corps, which included units of air force and air defense, fought in Korea on the Soviet side.

Thus, he was abroad for the first time, in the Chinese city of Dalian. There, his division was assigned a task, the performance of which took one month: Soldiers and officers had to relieve their comrades by providing military support to the fraternal Korean people.

The division headquarters were transferred to Andun, which is not far from the Chinese border with North Korea. This place was often visited by the legendary Soviet ace, Ivan Kozhedub, who taught Chinese and Korean pilots to fly the first jets (MiG-15s).

The Americans were based in South Korea and Japan. Their coalition forces, composed of 14 states, had powerful weapons and, above all, large and numerous modern aircraft. Therefore, Lt. Melteshinov, who served as the adjutant to the commander of the division, was in the thick of things.

F4U-5 Corsairs provide close air support to U.S. Marines fighting Chinese forces, December 1950

Cpl. P. McDonald/United States Marine Corps“Our air forces were suffering heavy losses,” writes Melteshinov. “At that time, the most modern aircraft, the F-86 Sabre, started to come off the assembly lines in American factories. They were equipped with radar and guidance systems. Their turning radius was just one hundred meters [about 330 feet]. That is why our pilots had a rough time. The MiGs were inferior to Sabres in many respects. We helped our air forces as much as we could.

“However, the U.S. planes often worked at heights of more than seven kilometers [4.3 miles], and so anti-aircraft artillery shells burst in the air without doing any harm to them. That is why our fighters always wore helmets, as well as full combat gear. Shards of our shells, falling from an altitude of several kilometers, were often fatal to Soviet anti-aircraft gunners. The enemy carried out bombing raids at night. Americans were using napalm back then. We buried our soldiers in the Russian cemetery in Dalian, while dead officers with the rank of major and higher were sent home.

“Our division was deployed next to a small Korean village near Andun. We were always happy when we shot down an American plane. However, our headquarters required evidence of downed planes. Therefore, the Koreans created special units, which were engaged in searches for evidence. During the first nine months of service, our division brought down 52 Sabres. Only once our joy was darkened: One of the Korean pilots flew a MiG to Seoul, defecting to the enemy.”

“Americans then dropped leaflets on our positions, urging us to do the same. However, they were mistaken in their estimations. Soviet soldiers had very warm relationships with the Chinese and Korean fighters. On the first of October, the Chinese invited us to celebrate their holiday; we sat at a table and shared a meal, and, on the first of May and the seventh of November, we invited them to our celebrations.”

Melteshinov’s service went through its normal course. Once, he even managed to go to Khabarovsk to see his family for a couple of weeks. He went to Beijing on special occasions. He carried a phrasebook to communicate with friends. The Koreans and the Chinese called all Soviet military men by the same name —“Captain.”

It was forbidden to come closer than 37 miles to Pyongyang. At that time, the United States accused the Soviet Union of providing military aid to Korea. Soviet diplomats categorically rejected this accusation. Therefore, the Americans decided to capture a Soviet pilot. To prevent this, Soviets had to take special measures—including in their free time.

In their free time, anti-aircraft gunners would catch fish in the local river, which delighted the Chinese and the Koreans. Most of the local population was poor, and they had never seen hooks and fishing rods before. On the other hand, Soviet military men were surprised by the wit and skills of their “brothers in the building of socialism.”

“The Chinese caught fish using pelicans. A hungry pelican was tied to a rope and its throat was restricted by a tight ring to prevent it from swallowing. The pelican would catch a fish, and the fisherman would take the fish from its mouth. Well, it did not match the proverb: He who would catch fish must not mind getting wet. We laughed together, but still, our soldiers caught more fish.”

Food for the entire division was prepared by an old Chinese cook. He cooked delicious, hearty meals. Melteshinov remembers him to this day, though 50 years have passed since then.

“The two years spent in North Korea were not easy. We did not leave the place immediately after the end of military operations,” Melteshinov continues. “We taught the art of artillery to our friends. All the weapons remained there after our departure from Andun. We left through another border point. We did not manage to take anything with us, although, at that time, we received quite a good salary in yuan. It was possible to buy five beautiful suits with that money. Customs officers prohibited us from bringing even a piece of clothing… Later they were criminally charged for these unauthorized activities.”

Melteshinov dreams of going to North Korea once again. Soon they will be celebrating the 60th anniversary of the end of the war. However, if he fails to get there, he will sit at a table with his comrades, the international soldiers, to recall those memorable years in the history of his country.

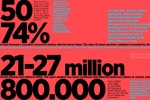

In 1952, 26,000 Soviet people and 321 aircraft were serving in Korea.

The Soviet Union was secretly involved in the war, so the pilots were forbidden to come near to the front line or to fly over the seas. Their planes bore Chinese insignia, and the pilots carried Chinese uniforms and Chinese documents.

Related:

Female face of war: Women in Russia’s armed forces

In the early stages of the action, the pilots were also required to not speak Russian during their missions and to learn essential Korean phrases necessary during an air fight. However, after the first battles, this requirement was removed, due to its impracticability.

The participation of Soviet pilots in this war was made public in the Soviet Union only in the 1970s–1980s. Despite all the secrecy, the U.N. pilots were well aware of who their enemies really were.

According to Soviet sources, the losses of the air corps during three years of war amounted to 335 aircraft, at least 120 pilots and 68 gunners. Whereas the enemy’s losses, according to the (inflated) data from the same sources, amounted to 1,250 aircraft, of which 1,100 were destroyed by the fighters and 150 by antiaircraft artillery.

First published in Russian in Artofwar.ru.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox