Moscow makes the case for school reform

Russia instigated a major reform of its educational system in 2010 to improve administration and quality. Source: EPA/Vostok Photo

When news came in fall 2012 that School 122 in central Moscow would be merged with another school, parents were up in arms. The school, which is the home of the Moscow Boys Cappella and requires all students to take choir, is one of the few places outside of conservatories where students can do coursework for a special diploma in music. Parents were afraid that the merger would not only result in the loss of the special music curriculum, but that it would “destroy the school’s unique culture,” in the words of one parent, whose daughter was then in the second grade.

The school was slated for consolidation under a controversial reform that began in 2010 and involves merging small or underperforming schools with larger schools primarily to more evenly distribute financial and administrative resources. Under the reform, funding for schools would be distributed on a per capita basis — a move officials said was necessary to accommodate an increase in demand.

“In our very large country, it is essential to ensure maximum equal access to early childhood services, and supplementary education,” said Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev, defending the changes, which went into effect Jan. 1, 2011.

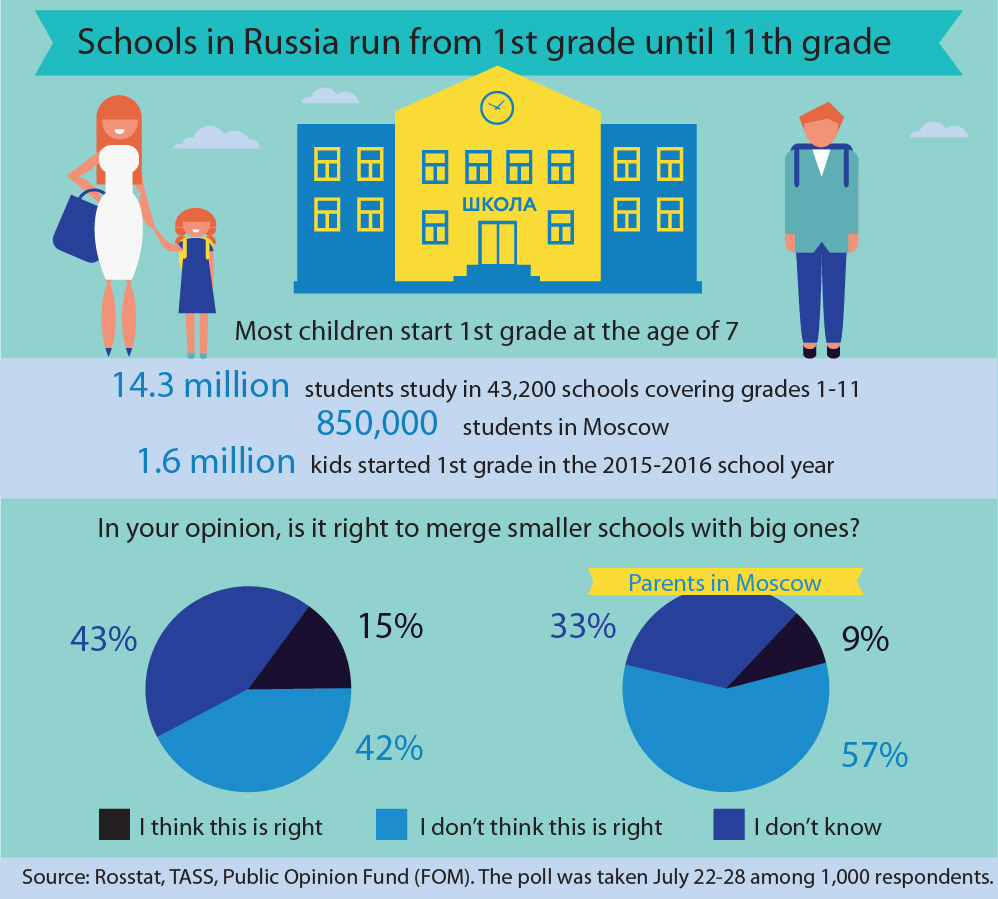

Russia experienced a baby boomlet during the economic prosperity of the early 2000s. Russia’s state statistics service, Rosstat, showed a steady increase in births from 2007–2012. In Moscow, 101,000 children were born in 2007. By 2012, that number had risen to more than 134,000. While some schools in the center of Moscow, like School 122, are undersubscribed, schools in the bedroom communities on the edges of the city, where young families moved into newly constructed apartment complexes, are overcrowded.

Click to view the infographics

Parents at Intellectual, a state-run boarding school for gifted students in western Moscow, took to the streets to protest the merger and expansion of their school, which had a student-teacher ratio of two to one. Students from the school took up the cause, writing letters to President Vladimir Putin and Moscow’s mayor and making a short film that was shown on local news portal Moskva24.

Moscow Deputy Mayor Leonid Pechatnikov responded in an interview with Russian daily Kommersant that if the parents wanted to keep that level of staffing, they would have to pay for additional salaries themselves. “We cannot afford to allocate 378,000 rubles ($5,640) per student. Two students for one teacher is, in fact, a system of tutoring. We have a law on universal education, but we do not have the law on universal tutoring,” Pechatnikov said.

The average amount per student spent in Moscow schools today is 63,000 rubles ($940).

In search of excellence

In addition to redistributing funding, the reform’s authors hoped to improve the performance of students on the Unified State Exam (E.G.E.), which is required for graduation from Russian schools, by combining schools with weaker academics with stronger ones.

Boris Kagarlitsky, a political scientist and the director of the Institute of Globalization and Social Movements, said that this second goal is at odds with the first one.

“In Soviet times, they sought to reduce class sizes so that the teacher could work with each student. Now per capita funding encourages schools to fill classrooms as much as possible, with fewer teachers,” Kagarlitsky said.

But other experts disagree with Kagarlitsky. Isak Frumin, a researcher at the Institute of Education of the Higher School of Economics in Moscow, said that forcing smaller schools to merge with larger ones will give more students access to high-quality education.

“There are several schools where the competition was dozens of people for one place, but now they were given additional space by combining with other schools and now they take more children. Opportunities to send a child to a good school have increased,” Frumin said.

Writing in a blog on the website of independent radio station Ekho Moskvy, local lawmaker Irina Kurash said that it is clear that the school reform has been a success — parents no longer have to “run around Moscow” in search of a good school and teacher salaries have increased as administrative costs were lowered, she wrote. Additionally, she noted, 13 schools in Moscow made it into the listing of the top 25 schools in Russia.

“Moscow finally has a fair system of financing educational institutions. Now funding decisions are based on standards and not the status of the school,” Kurash wrote. Previously school funding depended in part on the school’s designation, if it was classified as an ordinary school or had a title that indicated a special curriculum, such as “gymnasium.”

Out of options

Frumin said that no matter what experts and parents think of the reforms, they are necessary. This year, the number of children entering school in Russia has increased by 560,000 over last year, and the number is only going to continue to rise at least for the near future.

“In the next few years, we will need between 1 and 2 million new places,” Frumin said. “Either the number of children who will study in a second shift will increase, or we should put new school buildings into operation. This is a serious problem for the entire country; we are talking about hundreds of billions of rubles. The money has not been fully allocated for it.”

Over the past four years, 4,000 schools in Moscow have been combined into 692 larger institutions — including Intellectual, which merged with Gymnasium 1588, and School 122, which was united along with a kindergarten and a school with an intensive German-language program, with School 1234, an English-intensive school with a reputation for strong academics.

Results?

After the merger, the students remained in the same building and the music curriculum continued, but School 1234 brought in a new administration and some new teaching staff in the academic subjects in the upper school. The crumbling entryway and concert hall of the school’s 1930s building were remodeled and a new playground was installed. Now, two years later, the graduates of combined School 1234 scored so well on the E.G.E. that the school is now ranked 57th out of all schools in Moscow. After years of struggling to attract new students, the arts division introduced a first-grade class of 21 students at the opening bell ceremony on Sept. 1 and the school choirs held a concert as part of Moscow’s official City Day celebrations on Sept. 5.

“Things have changed for the better, and many of our fears were not realized,” said one parent with two children at the school, who declined to give his name.

According to a poll conducted by the Public Opinion Foundation (FOM) in July, his views are shared by only 15 percent of parents; 42 percent of Russian parents believe the consolidation of schools is wrong. But for nearly half of those who responded, the jury is still out — 43 percent of respondents told the pollsters the question was too difficult to answer.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox

.jpg)