Cricket in Russia: A search for new boundaries

The Russian team is using more home-grown players as the game grows in popularity. Source: Elena Pochetova

A Russian cricket team sounds as exotic as Swan Lake performed by Morris dancers, and not just to British ears. Few Russians know much about cricket, a game redolent of the British Empire. A fledgling cricket scene emerged in pre-revolutionary St Petersburg, but was swiftly halted by Communist suspicions about a “bourgeois”pastime. For most sports fans here, it’s an almost mythical activity with a bizarre lexicon of its own, often confused with the similar-sounding croquet.

Viktor Sukhotin, a Moscow-based member of Cricket Russia, has a definition of the game, however, that a member at Lord’s would easily recognise. “Cricket is a simulation of human life condensed into five days,” he says, a particularly ambitious claim in a country where five-day Test matches remain a distant dream. But ambition is one thing that Russia’s fledgling cricket community has in vast quantities. If those dreams are realised, a Russian team hopes to be able to host ICC tournaments and even play in future Olympics if the game returns to the world’s biggest sporting stage.

Sukhotin had an unusual journey towards cricket. In his childhood, which was spent mostly in China, he had some West Indian neighbours who introduced him to the rudiments of the game. Later, living in Hong Kong, he started to watch local teams. Now 36, he’s been playing organised cricket for about a year and, like many late starters, he finds many of the techniques take time to master.

“I played some street cricket when I was 13, but only sporadically,” he says. “At university, I was on the fencing team, but I also played tennis, which helps a lot. The hardest technique for me is the square cut and it took me all year to make any progress with my off spin.”

Developing local talent

Sukhotin is a beneficiary of Cricket Russia’s decision to pitch the game squarely at local players rather than maintaining the cosy expat club that had grown up around the United Cricket League in the capital. The organisation, which gained ICC affiliation in 2012, acknowledges that this was a divisive decision, but states its case plainly on its official website: “Unless we popularise cricket among native Russians and no longer remain as an expatriate-based cricketing community, Russian cricket will go nowhere. The Russian cricket team does not want to be taunted as an Indian or Pakistani Second XI and be the butt of jokes on social media.”

The national cricket team plans to host a four-nation tournament in Moscow in July. Source: Elena Pochetova

That process, spearheaded by Cricket Russia’s president Ashwani Chopra, has seen recent touring sides draw heavily on local talent, starting with a tournament in Bulgaria in 2012. The following year the national squad comprised 21 players and officials, 12 of whom were of Russian origin, while last month’s appearance at the prestigious Goa Premier League Twenty20 competition involved a squad of eight Russians and seven expats, including Chopra.

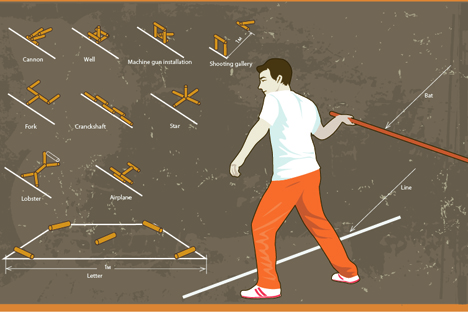

Another key part of the game’s development involves moving beyond Moscow. In Bataysk, a town near Rostov-on-Don, deep in the heart of Cossack territory, Konstantin Kiziavka is an evangelical convert to cricket’s charms. Unlike Sukhotin, Kiziavka came to the game via a traditional local sport, Chizh.

That bat-and-ball game, popular in the south of Russia, led him to baseball, which was “interesting, but didn’t capture my enthusiasm”. Then in 2007 he caught a glimpse of cricket, studied the rules and realised it was the game he was looking for. “It’s the perfect game with bat and ball, it couldn’t be better,” he says.

At first he played with friends and family, struggling for equipment (which has to be imported from England or India) and with the challenge of bowling with a straight arm. A few adaptations of the rules led to the creation of “Cossack Wicket”, or “Cwicket”, and the establishment of a mini-cricket league: games played with a single wicket and a taped-up tennis ball, open to men and women of all ages.

“We’ve taught about 500 people to play and we’ve run a league for the past three seasons,” Kiziavka says. “We got to know some Indian students and play both real cricket and Cwicket with them. We’ve also got a good relationship with Ashwani Chopra, and we’re looking forward to showing him what we’ve done here.”

There is hope of establishing regular “indigenous player tournaments” with teams drawn exclusively from domestically produced players. Source: Elena Pochetova

For Kiziavka, a local journalist, spreading the sport is a labour of love. The stripped down game in Bataysk recalls the impromptu street cricket seen in the Indian sub-continent, although for the moment it’s not easy to make the transition up to the fully fledged game.

He funds the costs of developing the league from his own salary and eagerly follows online broadcasts of the international game, with an affection for New Zealand and a soft spot for the controversial former England star Kevin Pietersen. With more investment and access to a full-size field, he’d love to play more full-size cricket, but the thrill of the first delivery every Sunday justifies the efforts to grow the game.

From Cwicket to cricket

Those efforts are an echo of the work done by Cricket Russia. After years of playing at Moscow State University’s Baseball Arena, with an artificial surface that offers little to the spinners and a lightning-fast outfield that punishes fast bowlers, the organisation now has its own field in the eastern Moscow suburb of Karacharovo and a further site near the city’s outer ring road.

Chopra has translated the rules of the game into Russian, making the sport less confusing for prospective players; Russian TV coverage on cable TV features commentators speaking a bizarre mix of English cricketing terms dragged through the complex mill of Russian grammar to produce a sonic soup that makes little sense to anyone.

The national team, which plays with an increasingly Russian accent, is competing more frequently with its peers in Eastern Europe and plans to host a four-nation tournament in Moscow in July. With support from the ICC, there is hope of establishing regular “indigenous player tournaments” with teams drawn exclusively from domestically produced players under 25 – no naturalised expats, no Russians returning from school or university in a cricket-playing country. That would capitalise on the interest already shown among 600 or so players involved in 44 regional centres.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox