Valeri Kharlamov: little genius of the big game

The story of the legendary Soviet hockey player whose life was cut short. Source: Sergei Mikheyev/RG

Half Spanish, half Russian, Valeri Kharlamov, who played for CSKA Moscow in the Soviet League from 1967 until 1981, was one of the most brilliant hockey players of his era, despite his diminutive stature. Part of the utterly dominant Soviet “invincibles” of the 1970s, the speedy Kharlamov’s finest hour was his stunning performances in the Super Series of 1972, the first competitive matches between Canada and the Soviet Union.

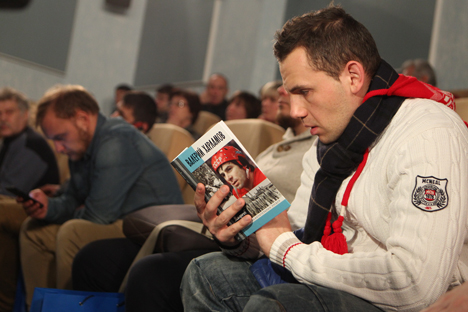

Now fresh details are emerging of the life and untimely death of the late Soviet hockey star in a new biography, titled simply Valeri Kharlamov. Written by Maxim Makarychev, the book tells the story of the short but glorious life of the USSR’s number 17 and his difficult path to the pinnacle of world hockey. A significant part of the book is devoted to the memories of the people who knew Kharlamov closely.

Valeri Kharlamov was born on January 14, 1948 in Moscow and died on August 27, 1981. A forward for the CSKA club and the USSR national team, Kharlamov was a two-time Olympic champion, eight-time world champion, seven-time European champion, eleven-time champion of the USSR and an 11-time champion of the European Champions Cup. He scored a total of 293 goals in the national championships. In the world championships and the Olympic Games he scored 87 goals. He played a total of 286 games and scored 185 goals for the USSR national team.

Makarychev, who is also a journalist for the Rossiyskaya Gazeta newspaper, has already penned biographies of the Cuban leader Fidel Castro and hockey player Alexander Maltsev.

Spanish blood

Half Spanish, Kharlamov was born into a Moscow working family. His father, Boris Kharlamov, was a metalworker and his mother, Begoña Orive Abad, was of Basque origin. She was one of the children of a Spanish communist who had fled the Franco regime to the USSR before the beginning of WWII.

"He had a mixture of Spanish and Russian blood, which is why he was unique in life and on the ice," said Kharlamov's childhood friend, famous Russian footballer and coach Vadim Nikonov. During Soviet times Kharlamov, who played for CSKA and the national USSR team, was loved regardless of club preferences.

He was one of Moscow's great mods, one of the few who would wear a golden necklace as thick as a finger during the tough Soviet times. He was the best dancer among the hockey players, heeding the calls of his Spanish blood, performing fiery flamencos and exhilarating rock and roll.

Carrying his stick and equipment bag, he once arrived at a friend's wedding directly from the airport after having played in a different city and said, "Sorry, my friend, I didn't have time to buy a gift." After which he took off his fashionable new shirt and gave it to the groom. Then he opened his bag and put on his CSKA jersey with the number 17, which, by the way, the army club has since retired in honor of Kharlamov.

The Russian ice legend

Probably the most revealing part of the book is the section describing the 1972 Super Series with the Canadians.

"It was the first time players of our generation crossed sticks with NHL players," said Kharlamov's best friend, two-time Olympic ice hockey champion Alexander Maltsev. "I know that we will never see matches like the ones of the 1972 series again. There will be others - better, worse, but not the same. We were making history. Hockey history, at least."

Kharlamov's brilliant talent fully manifested itself in the first game of the Super Series, when the USSR national team created a real sensation by beating the Canadian professionals 7-3 in Montreal. North American experts had been unanimous in their predictions that the Russian team would lose all eight matches.

Harry Sinden, who coached the Canadian team in 1972, immediately, right after the first game, understood that Kharlamov, with his "profound mastery," was the key element of the Russian attack. "He was our main target," Sinden admitted years later. "I was tormented each night by thoughts on how to contain this guy. He was real dynamite."

‘Soviet millionaires’

"In 1972, when we won the game in Montreal, Kharlamov, Petrov and I were approached by the owner of Toronto, who offered us money to play for his team," recalls Boris Mikhailov, captain of the USSR national team. "When he told us the amount, I said that we were Soviet millionaires. Later we thought, why not try playing for the NHL. But back then we didn't even imagine defecting. We had been brought up with different values. We had to prove that our Soviet system was the best."

In the 1970s, when Viktor Tikhonov became coach, Kharlamov was the main striker of the so-called ‘Red Machine’. From 1981 to 1985 the USSR national team did not lose a single match during international competitions. Western analysts often wondered how it was possible that under the Communist system the USSR national team played such free, venturesome and bold hockey. The explanation is simple. These players, who spent 11 months together as a team, reached such a level of mastery and mutual understanding that they could play with their eyes closed.

An honest hero

At the end of August 1981 Tikhonov did not invite the 33-year-old Kharlamov to the national team for the Canada Cup. The coach said that the player was not in good shape, even though several weeks earlier Kharlamov had been nominated best forward of the European Champions Cup. Kharlamov was not himself. He was depressed and on that fatal morning of Aug. 27, when he was returning to Moscow from his country home, he let his wife drive the car, which he had never done. The big Volga skidded on the rainy road and slammed head-on into a trailer loaded with nails, killing Kharlamov and his wife instantly.

The entire city of Moscow came out for Kharlamov's funeral. Thousands and thousands of people went to the CSKA Palace of Sports to participate in the farewell ceremony. "My last words at the funeral were… I said that Kharlamov did not understand his distinction," great Soviet coach Anatoly Tarasov would later write. "He did not see the real scale of his incredible gift. He never, in front of no one, demonstrated his exclusivity and was an unusually decent, pure and honest individual."

Read more: Passing of Viktor Tikhonov is an epitaph to a vanished sporting era

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox