A whirlwind of architecture and history within the walls of an ancient fortress

Derbent's prominence can be explained relatively easily: it sits in an important military and trading position, spanning the narrow strip of land between the Caucasus mountains and the Caspian Sea. Caravans following the Silk Road passed through Derbent.

The Great Caucasus Wall

Derbent's value as a border outpost is visible to the naked eye. The mountains end just a kilometer from the sea and the Naryn Kala fortress ("Sunny Fortress", it really is very sunny here) looms over the shore. The two almost parallel walls of the fortress stretch down to the sea. In the 20th century they were partially dismantled, as they were deemed unnecessary, but their footprints can still be made out today from the air. The streets that run across Derbent were built right along the walls. Long ago the walls went a few hundred meters into the sea, forming a convenient harbor. In modern times, archaeologists have found the remains of the wall at the bottom of the Caspian Sea.

Besides this, the walls of the fortress went even farther, they stretched for 70 kilometers into the mountains, forming the Caucasian version of the Great Wall of China. The wall was built for exactly the same reason as the Chinese one was -- the wall of Derbent prevented invaders from getting around from either the sea or the land. Derbent's beauty was noted by even the famous Alexandre Dumas, author of "The Three Musketeers" and "The Count of Monte Cristo." "Derbent is a huge wall that blocks the road, stretching from the mountain tops to the sea. Before us were just massive gates that, judging by their design, were examples of formidable Eastern architecture made to defy the ages," he wrote in "Tales of the Caucasus," which was inspired by his trip to Russia.

Minus 3000 years

Archaeological excavations have shown that the first settlements appeared here in the Bronze Age, at the beginning of the third millennium BC, so now the city is decorated with somewhat tacky signs proclaiming "Derbent is 5000 years old." This is, of course, an exaggeration, but not a very big one. Derbent was first mentioned by Hecataeus of Miletus (6th century BC), who called it the Caspian Gates.

Local and federal authorities are still trying to figure out the exact dates. In 2010, local mayor Imam Yaraliev proposed marking the 5000th anniversary of Derbent, and in 2013 the Kremlin adopted a decree that the 2000th anniversary of the city will be celebrated in 2015. Locals think the decision is a political one. It's a little awkward, afterall, that the oldest Russian city is located in the Northern Caucasus, and not on the Golden Ring.

The fortress that can be seen today - a mountain wall and fortified port - was built by the Persian Shah Khosrau I (531-579) of the Sasanian dynasty. It is interesting to note that he built it using money from Byzantium. Justinian I assisted his neighbor in defending itself from the northern nomads. After strengthening his defenses, Khosrau went to war against Byzantium.

Walls up to 20 meters high are built of huge blocks of yellow limestone, which was used to build the rest of the city. Medieval Arab geographers wrote enthusiastically about how thick the Derbent walls were, each trying to outdo the other. One calculated the thickness in the number of wagons that could drive along the top at the same time. Another, for example, swore that 20 horsemen in a row could ride along the top of the wall. In fact, the walls are about 5-7 meters thick. A cavalry unit would not fit on top, but it was enough to impress in its time.

Artifacts of the citadel

Right at the entrance to the Naryn-Kala Fortress is a fountain with water from the mountains that is shaped in the form of some fantastic beast, and a small zindan, which is basically a hole in the ground used for confining prisoners. Actually "zindan" means "pitcher". It is a stone bag with a narrow opening at the surface so the prisoners couldn't climb up its sheer walls. The floor is covered with coins. For some reason this is the spot that all tourists want to return to.

The zindan is right next to the khan's office. It was here that defendants waited for the court to hand down its decisions. If someone was found guilty, and most were in those days, the poor guy was transferred to the large dungeon. It was also located in the fortress, but was taller and built in the same way, with a narrow opening at the surface and a deep impenetrable space. Neither the floor nor the walls can be made out.

"Prisoners were held here for life," the tour guide said respectfully. But he added immediately, "However, they usually lasted about three months." As he explained, the corpses were not removed from the dungeons, and so the prisoners spent their days along with their dead predecessors.

They continued to feed prisoners, as was expected at that time, but the khan saved a lot on food due to the putrid conditions. "In the 1980's they were doing excavations and found a meter of bones!" the tour guide noted helpfully.

Nearby is a collection of anchors. The newest are Russian, and then come their counterparts from thousands of years ago -- stone plates with holes.

Naryn-Kala has an eclectic mix of architecture from different eras. There are Iranian baths from the 17th century arranged so that they could be heated by a single candle. Here you can also find the khan's palace with a dried up pool.

There are also the western gates of the fortress that were rebuilt in the 10th century. Derbent residents called them the "gates of shame" because if the fortress was in danger of being overtaken, the ruler could escape through them into the mountains. Nearby is a Russian guardhouse. "From the beginning of the 19th century in the provincial style of the Russian Empire," reads the plaque on the wall. And there's a shed built by Soviet archaeologists about 30 years ago. I do not know whether it will last as long its neighbors, but now it plays the important role of housing sheep, who think nothing of wandering between ancient relics and along the castle walls.

Ancient Province

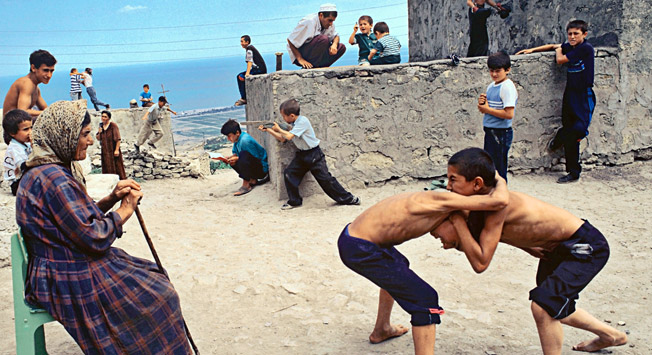

The route from there to the Old Town goes down a very long medieval staircase. There are exactly 211 steps. Old Derbent is squeezed in between the two walls of the fortress. The distance between them is less than half a kilometer. Judging from photos from the 1970's, the entire city fit between the two walls at that time. That's probably why the cobblestone streets are so crooked. A person can get lost here even with a map, and the streets are so narrow that the only thing that can drive along them are three-wheeled motor scooters. Since then Derbent has grown. Now beyond the walls is an unkempt town, similar to others in the Russian province.

In the Old Town the whirlwind of architecture continues. You can find a caravanserai (a medieval roadside inn for merchants), the mausoleum of Persian Hanshi Tuti-Bike, and an Armenian church. There are a couple of medieval baths, including one especially for unmarried girls. But the most interesting building is the Juma Mosque, the oldest mosque in Russia, built in the 7th century. In its quiet courtyard is an 800-year old plane tree.

People who want to take a break from religion can visit the most secular institution in Derbent - the famous brandy factory. Besides the brandy, I personally liked the Soviet-era mosaics best of all. They were just as fascinating as Roman or Byzantine mosaics in the Mediterranean. The Derbent mosaics also belong to history, and they are only a few decades old.

Dmitry Vinogradov, RIA Novosti

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox