No time for the past as Sochi embraces glamorous new role

According to western analysts, Sochi was destined to become a post-Olympics white elephant.

Getty ImagesDaniil and Elena have travelled a long way. Sensibly, they transported their car by train, but if they’d driven, it would have been almost 6,000 miles from their old apartment in Vladivostok to Sochi, where the couple now hope to live. Finding a home in Russia’s subtropical paradise is far more difficult than they’d imagined.

Their bubbly estate agent, Irina Nikolayevna, explains that there’s now a housing shortage in the resort city and that she thinks the pair are being too choosy.

“They only want up to the third floor. They need secure parking. They are afraid of gas cookers,” she snorts. Fussy Russians isn’t a new thing, but a lack of residential properties in Sochi certainly is.

“There are huge numbers of people moving here. Especially in the past year. Rents have increased, across the city. I rented this flat last year to a man from Minsk. It was 25,000 rubles ($390) then. Now it’s 40,000, ($620)” explains Nikolayevna.

It wasn’t supposed to be like this. According to western analysts, Sochi was destined to become a post-Olympics white elephant. Too expensive and too Russian for cosmopolitan Muscovites, who would always prefer to vacation in Europe or Asia.

"The Winter Olympics were meant to be the culmination of Vladimir Putin’s 14 years in charge of Russia," wrote one western reporter. "Sochi itself was given a major makeover, but the alleged huge corruption involved in the construction and the “white elephant” nature of many of the stadia has left locals wondering if it was worth it."

Ruble decline

Then the price of oil nosedived and the ruble crashed from around 42 to the euro in 2013 to a January 2016 low of about 90. Despite a recovery to close to 75, travel to the likes of Tenerife and Majorca remains almost two times more costly for Russians than before. Sochi, after a make-over believed to have cost $50 million prior to the 2014 winter games, stood ready to capitalize.

Thus, while the rest of Russia is cowering from recessionary blues, Sochi is enjoying an unprecedented residential building boom. Cranes dominate the city skyline and construction sites are operating both day and night.

Yet, despite the flurry of activity in central Sochi, the oft-criticized Olympic Park, in the southern Adler district, remains a hard sell. The problem with the Olympic zone is that it’s too far from the city.

“If you don’t drive, you need a train, which takes 30 minutes to the center and a bus for 15 minutes of top of that to get to the railway station. If you drive, it’s better to live in Lazerevskoye (north Sochi) where property is cheaper and communities are more settled,” says Ashot Andreasyan, a landlord.In a bid to populate the area, the regional administration recently conducted something of a fire sale of Olympic Village housing, with heavily reduced prices. The strategy hasn’t yielded instant results.

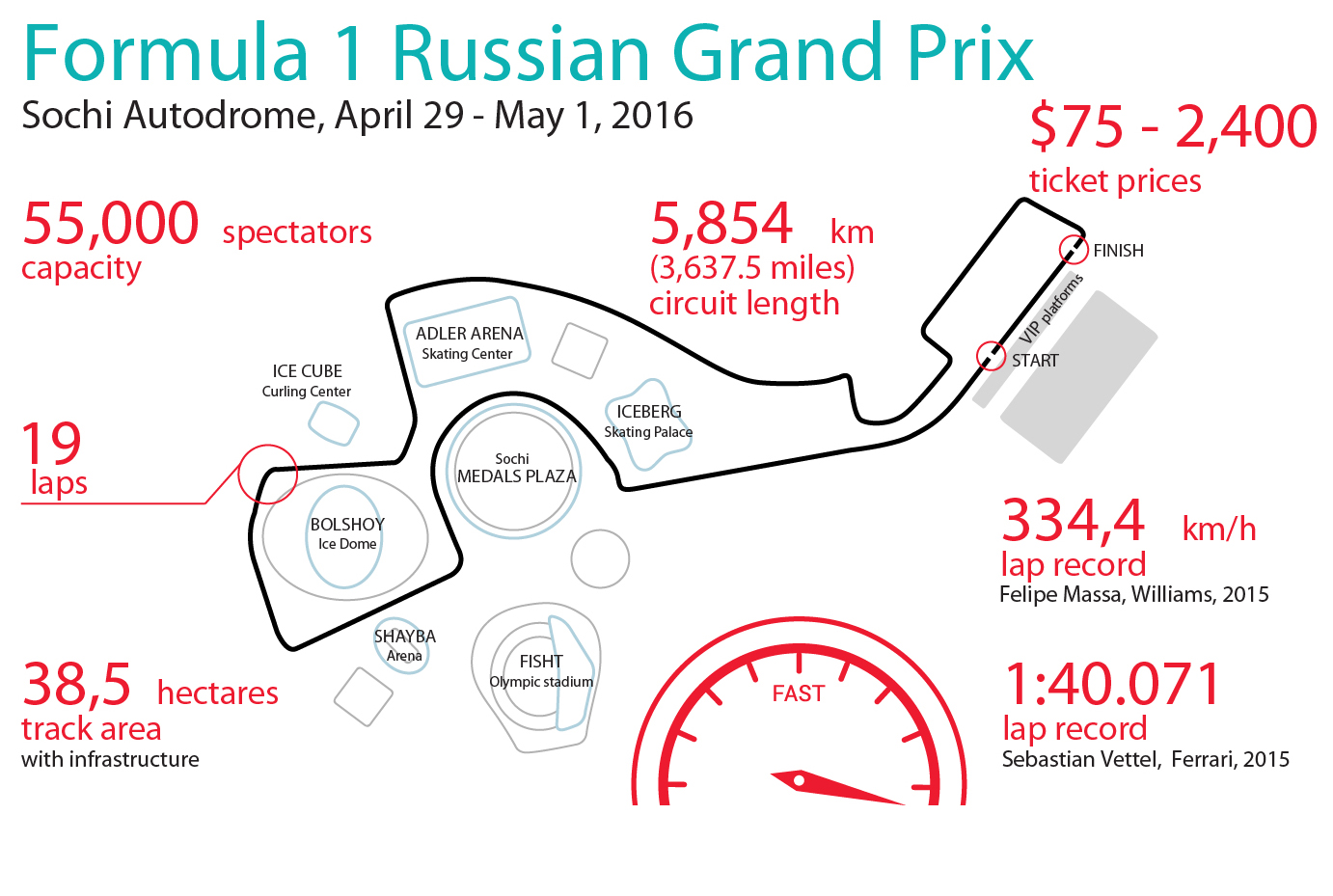

“In theory, this was a good idea but what’s happened instead is that well-off people from Moscow and St. Petersburg have bought these properties and will use them in July and August and maybe for the Formula One weekend [in May].” Andreasyan explains.

Yet, central Sochi, 21 miles up the road, is congested. Traffic jams are now a daily feature and the old ethnic make-up is changing radically.

“A few years ago, this was little more than a village, mainly populated by Armenians. Now you meet people from all over. My immediate neighbors today are from Novosibirsk and Magadan. It’s very exciting for me,” enthuses Elza Kondakchyan, a young sales manager.

“Before, we had a few shashlyk places and stoloviye (Russian canteens). Now we have Chinese and Korean restaurants. This used to be unthinkable,” she adds.

Exotic cuisine

At Seoul-Korea, the restaurant’s chef has migrated from Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk, a city on the Russian island of Sakhalin close to Japan. Restaurant administrator Stella says there is a burgeoning Korean community in Sochi.

“We are very busy here. We get locals and new arrivals from the Far East, where Korean food is very popular.” Stella agrees that housing is now a big issue in Sochi.

“A lot of new customers come here to eat and then, on the way out, ask can we help them find a flat. We are half thinking of opening an estate agency upstairs,” she says.

Russia is currently seeing significant migration to the Krasnodar Territory, the country’s warmest region. While almost all other cities outside of Moscow and St. Petersburg have shrunk in population in the past three decades, Krasnodar itself has exploded from 620,516 in 1989 to an estimated 829,700 today.Meanwhile, Sochi has increased from 385,851 residents to approximately 477,000 in 2016. It’s generally believed this figure is conservative, as it’s based on the 2.5 percent growth rates seen from 2002-10, which have mushroomed in recent years.

Further up the coast, places like Anapa, Gelendzhik and Tuapse, which were once little more than villages, are swelling too. While prices are much lower, they lack the infrastructure and attractions of the larger cities.

In Sochi, rapid expansion has brought prosperity to some business people and property owners. The new Rolls Royce and Porsche cars frequently parked outside the expensive Lighthouse and Syndicate restaurants are evidence of that. However, rising prices are making life much tougher for people outside of the elite.

“Most people here are earning between 30,000-40,000 roubles ($470-620) a month. Small flats now cost a minimum of 5 million rubles, ($78,000). "Us locals are being priced out,” complains Elza.

At Kokos, Sochi’s funkiest hipster bar, a bottle of beer costs 400 rubles ($6.20) and a cocktail comes to around 600 rubles. On a busy March night, there were customers from Moscow, St. Petersburg, Khabarovsk and Krasnoyarsk. Yet, not a single Sochi native. Either the city’s new affluence is out of reach for them or they are too sensible to pay such inflated prices. Or maybe it's a mixture of both.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox